-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Carla I.J.M. Theunissen, Frank F.A. IJpma, Primary umbilical endometriosis: a cause of a painful umbilical nodule, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2015, Issue 3, March 2015, rjv025, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjv025

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A female patient presented with a painful swelling in the umbilicus. Ultrasonography demonstrated a hypodense nodule of 1.8 cm. Surgical exploration revealed a subcutaneous, dark discoloured, lobulated swelling at the bottom of the umbilicus, which turned out to be primary umbilical endometriosis (PUE). Primary umbilical endometriosis is a rare and benign disorder, caused by the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue in the umbilicus, which can present as a painful, discoloured swelling in the umbilicus. The clinical distinction between primary umbilical endometrioses and other causes of an umbilical nodule is difficult. Additional imaging modalities do not show any pathognomonic signs for establishing this diagnose. Surgical exploration and excision are a safe and definitive treatment of primary umbilical endometrioses. This case highlights the importance of including PUE in the differential diagnosis of women with a painful umbilical nodule.

INTRODUCTION

Endometriosis is a common benign disease, which is defined by the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus that most often affects the pelvic peritoneum [1, 2]. The presence of endometriosis in the umbilicus does rarely occur [3]. Primary umbilical endometriosis (PUE) is often not recognized based on its clinical appearance, and knowledge about the pathophysiology is scarce [2].

We report here a rare case of a painful, livid coloured nodule in the umbilicus, which turned out to be PUE. PUE should be a differential diagnostic consideration in patients with a painful swelling in the umbilicus as is outlined in this report.

CASE REPORT

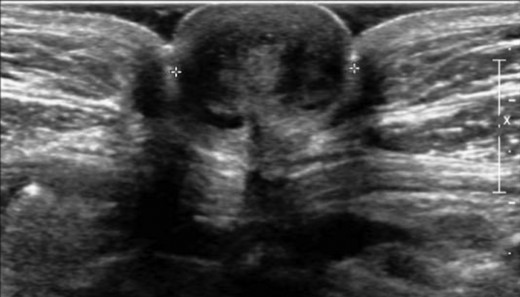

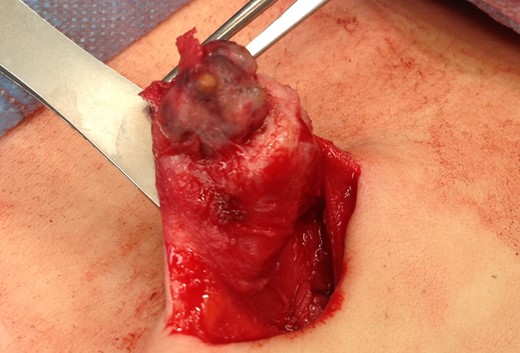

A 47-year-old healthy female presented with a painful and livid coloured nodule in the umbilicus, which gradually evolved over the past 6 months. She had no symptoms of dysmenorrhoea or cyclical umbilical pain. At physical examination, she had a soft, painful swelling with a diameter of 2 cm in the umbilicus, which was irreducible by gentle digital pressure (Fig. 1). Ultrasonography revealed a hypodense nodule of 1.8 cm at the umbilicus (Fig. 2). However, a definitive diagnosis could not be established thus far. Under the provisional clinical diagnosis, ‘irreducible umbilical hernia with probably strangulated fatty tissue in the hernia sac’ surgical exploration of the umbilicus was performed. Under general anaesthesia, a sub-umbilical incision was made. To our surprise, a subcutaneous, lobulated mass was exposed, which was fixated on the bottom of the umbilicus (Fig. 3). The abdominal wall itself was unaffected. The nodule was excised, and histopathological examination revealed connective tissue fragments with irregular tubular formations surrounded by stromal cells. Our patient was treated by excision of the swelling that turned out to be PUE. Two months after the surgery, she visited the outpatient clinic and reported complete recovery of the painful sensation and swelling in the umbilicus.

Clinical presentation of a livid, soft, painful swelling in the umbilicus, which could not be reduced by gentle digital pressure.

Ultrasonography of the umbilicus demonstrated a hypodense nodule of 1.8 cm in the umbilicus.

Intraoperative image of dark discoloured, lobulated swelling at the bottom of the umbilicus that turned out to be PUE.

DISCUSSION

Endometriosis is a benign disorder, which affects 6–10% of all women in the reproductive age [1]. The umbilicus could be an extraordinary site of endometriosis and is affected in 0.5–4% of the women with endometriosis. Umbilical endometriosis could have a ‘secondary’ nature, but this disorder can also be spontaneous or ‘primary’ [2]. In the English literature, only 37 cases of PUE have been described. The pathogenesis of PUE is not fully elucidated. Possible explanations for PUE could be the migration of endometrial cells to the umbilicus through the abdominal cavity, the lymphatic system or through the embryonic remnants in the umbilical fold such as the urachus and the umbilical vessels [3–5]. Secondary umbilical endometriosis is caused by iatrogenic dissemination of endometrial cells, for instance, after a caesarean section or laparoscopic operation [1, 2, 4]. Other causes of a painful swelling in the umbilicus are shown in Table 1 [3–5].

| Benign . | Malignant . |

|---|---|

| Cutaneous endometriosis/endosalpingiosisa | Sister Mary Joseph nodeb |

| Haemangioma/vascular malformation | Melanoma |

| Umbilical hernia/cicatrical hernia | Sarcoma |

| Sebaceous cyst | Adenocarcinoma |

| Granuloma Lipoma Abscess Keloid Omphalomesenteric or urachus anomaly and/or infection Desmoid tumour | Lymphoma |

| Benign . | Malignant . |

|---|---|

| Cutaneous endometriosis/endosalpingiosisa | Sister Mary Joseph nodeb |

| Haemangioma/vascular malformation | Melanoma |

| Umbilical hernia/cicatrical hernia | Sarcoma |

| Sebaceous cyst | Adenocarcinoma |

| Granuloma Lipoma Abscess Keloid Omphalomesenteric or urachus anomaly and/or infection Desmoid tumour | Lymphoma |

aEndosalpingiosis: the presence of fallopian tube-like epithelium outside of the fallopian tube.

bSister Mary Joseph node: palpable nodule bulging into the umbilicus as a result of metastasis of a malignant tumour in the pelvis or abdomen.

| Benign . | Malignant . |

|---|---|

| Cutaneous endometriosis/endosalpingiosisa | Sister Mary Joseph nodeb |

| Haemangioma/vascular malformation | Melanoma |

| Umbilical hernia/cicatrical hernia | Sarcoma |

| Sebaceous cyst | Adenocarcinoma |

| Granuloma Lipoma Abscess Keloid Omphalomesenteric or urachus anomaly and/or infection Desmoid tumour | Lymphoma |

| Benign . | Malignant . |

|---|---|

| Cutaneous endometriosis/endosalpingiosisa | Sister Mary Joseph nodeb |

| Haemangioma/vascular malformation | Melanoma |

| Umbilical hernia/cicatrical hernia | Sarcoma |

| Sebaceous cyst | Adenocarcinoma |

| Granuloma Lipoma Abscess Keloid Omphalomesenteric or urachus anomaly and/or infection Desmoid tumour | Lymphoma |

aEndosalpingiosis: the presence of fallopian tube-like epithelium outside of the fallopian tube.

bSister Mary Joseph node: palpable nodule bulging into the umbilicus as a result of metastasis of a malignant tumour in the pelvis or abdomen.

In the majority of cases, the clinical manifestation of PUE consists of an umbilical nodule. This could be associated with cyclical pain or a bleeding tendency from the umbilicus. Instead of ‘cyclical’ pain, patients could have ‘continuous’ umbilical pain, like in our case. The nodule may have a brown, blue or dark discolouration [3].

Little is known about the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography, CT scan and MRI in diagnosing umbilical endometriosis. No pathognomonic signs of PUE have been observed at one of these imaging techniques. Ultrasonography can provide some information about the size of the nodule and its adherence to surrounding tissues [5, 6]. However, in our case, it was not possible to establish a definitive diagnosis with ultrasonography. Furthermore, CT scan and MRI are also of little value in diagnosing intra-abdominal endometriosis [7, 8].

In patients with a symptomatic umbilical nodule due to PUE, surgical exploration and excision of the nodule should be considered. Recurrence of PUE after thoroughly surgical excision is rare [3]. The patient in our case had no symptoms of extensive intra-abdominal endometriosis such as dysmenorrhoea. When patients do have clinical symptoms of intra-abdominal endometriosis, referral to a gynaecologist is mandatory. Treatment of umbilical endometriosis with hormones might be different approach for this condition and can diminish clinical symptoms temporarily. However, after the cessation of hormonal therapy, it is likely that the symptoms will reoccur. Agonist of gonadotropin-releasing hormone and oral contraceptives are most frequently used hormones to treat endometriosis [1, 3].

In conclusion, by increasing the awareness of PUE as a potential diagnose in women with a painful, sometimes discoloured, umbilical swelling, we hope this condition will be recognized and treated optimally.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.