-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Thamer A. Bin Traiki, Ahmad A. Madkhali, Mazen M. Hassanain, Hemobilia post laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2015, Issue 2, February 2015, rju159, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju159

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm is a rare complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A high index of suspicion and early identification and therapy are important points needed to prevent rupture. We report a case of complex biliary and vascular injuries 4 weeks after a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The patient had recurrent bleeding from a hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm that has been treated successfully with angiographic stenting and embolization.

INTRODUCTION

Vascular injuries leading to pseudoaneurysm and bleeding are rare complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. These injuries can occur in a fashion similar to those of the biliary system, resulting in laceration, transection or occlusion of the hepatic arterial. This case report describes a patient who presented with acute bleeding from a pseudoaneurysm of the replaced right hepatic artery and the left main hepatic artery following a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

CASE REPORT

A 64-year-old male referred to our hospital 4 weeks after having a laparoscopic cholecystectomy complicated by a common bile duct injury. He had undergone a difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy with intraoperative bile duct injury suspected at the end of the procedure at a peripheral hospital. The surgeon inserted a drain in the surgical bed at the time of the surgery. Postoperatively, the patient was started on piperacillin and tazobactam, and underwent an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which confirmed the presence of a common bile duct injury. A biliary stent was placed. The patient continued to have daily bile drainage ranging from 100 to 350 ml per day.

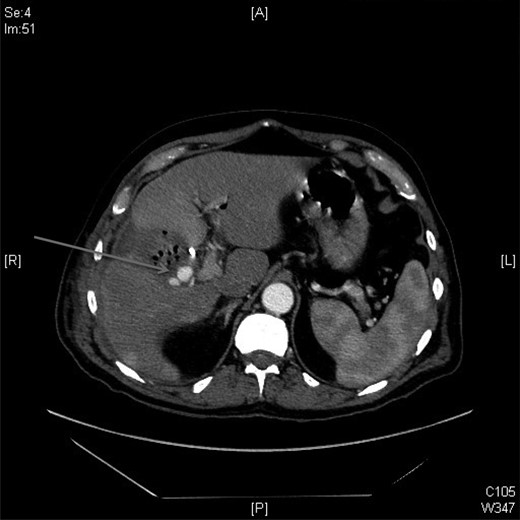

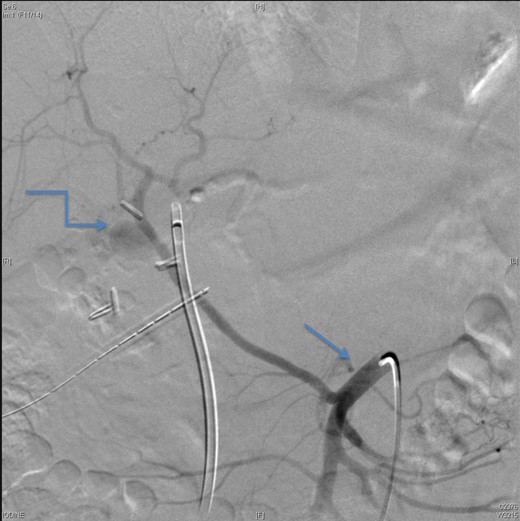

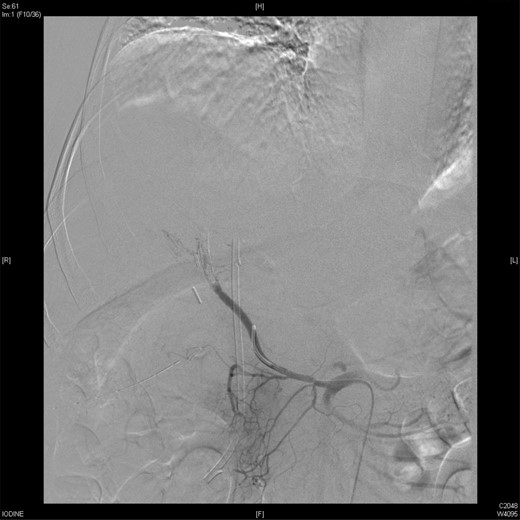

Upon presentation to our center, the patient was febrile (38.9°C) and complained of a left upper limb pain and swelling. The surgical drain was draining a mixture of bile and blood. His WBC count was 14 × 109/l, total bilirubin 35 µmol/l and the direct bilirubin 21 µmol/l. A duplex ultrasound of the upper limb revealed a left brachial vein thrombosis. Hematology was consulted, and a diagnosis of acute upper limb venous thrombosis was established. Owing to the presence of blood in the drain, he was kept on the maximum prophylactic dose of unfractionated heparin. A CT angiography of the abdomen showed two collections, one at the surgical bed near the drain, and the other was subcapsular below the left lateral lobe of the liver, as well as an aneurysm of the replaced right hepatic artery with an active bleeding blush (Fig. 1). The patient was immediately referred for an angiography, which confirmed the CT scan findings (Fig. 2). An arterial stent was inserted at the location of the aneurysm (Fig. 3), and a pigtail drain was inserted to drain any residual collection. An ERCP was also performed, which revealed a Strasberg Class D injury, and a plastic biliary stent was inserted. After the angio-stent insertion and stabilization of the patient, heparin infusion was started. Five days later he developed hematemesis and melena with a significant drop in his Hb to 2 g/l, and his total bilirubin became 183 μmol/l of which 91 μmol/l is direct. A gastroscopy was performed and showed hemobilia (bleeding from the ampulla of Vater). Subsequent angiography demonstrated a leak of contrast just above the arterial stent; hence, a further stent was placed to cover that area of the aneurysm. Similar symptoms reoccurred a week later, and a new angiography showed a new aneurysm from the left proper hepatic artery. A percutaneous thrombin injection of the aneurysm was performed as the bleeding branch was unreached via direct angiography and was filling in retrograde perfusion. During recovery a chest spiral CT was performed, which revealed the diagnosis of a bilateral segmental pulmonary embolism. Heparin infusion with low targets of partial thromboplastin time of 50–60 was started.

A CT scan showed replaced right HAP inside the collection (straight arrow).

An angiographic scan showed superior mesenteric artery (straight arrow) and replaced right HAP (angulated arrow).

An angiographic scan showed stent in the replaced right hepatic artery.

On Day 7, the patient bled again from the same aneurysm of the left hepatic artery. A repeated angiography revealed the bleeding with a reduced flow in the stented, replaced right hepatic artery (Fig. 4). The active bleeding was stopped using gel-foam embolization of the two branches of the left hepatic artery (Fig. 5) with a decision to embolize the whole left hepatic artery if bleeding did not stop while holding the heparin infusion. The patient's liver function was preserved, and the bleeding stopped despite anticoagulation.

An angiographic scan showed reduced flow in the stented replaced right hepatic artery.

DISCUSSION

A laparoscopic cholecystectomy is reportedly associated with an increased incidence of biliary and vascular injuries. Specifically, biliary injuries are reported in 0.2–1% of procedures with a 10-fold increase when compared with open surgery, whereas vascular injuries occur in 0.25–0.5% of procedures [1]. The symptoms may appear in the early postoperative period or as late as 120 days after operation [2]. Our patient presented a month after surgery.

A pseudoaneurysm of the hepatic artery or its branches can lead to bleeding through the drain or in the form of hemobilia in ∼20% of cases [2]. However, the classical clinical triad described by Quinke [3] of right upper quadrant pain, jaundice and hemobilia has been reported in 32% of patients with laparoscopic cholecystectomy-related hepatic artery pseudoaneurysms (HAPs) [4]. The clinical presentation of HAP is bleeding, which might be intermittent bleeding if discovered early. If it is not identified, a massive hemorrhage may occur with a rupture, and the mortality rate could be as high as 50% [5]. In our patient, the symptoms were fever, jaundice and blood from the drain. Later on, he had symptoms of acute gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.

The pathogenesis of post cholecystectomy HAP is unclear. Direct vascular injury, erosion due to clip encroachment and diathermy shorting on clip-associated infections [6] are likely to be precipitating factors. Bile leak and secondary infection are the most important factors. Bile is cytotoxic and the amphipathic properties of bile acids make them powerful solubilizers of membrane lipids, causing cell death. A canine study by Sandblom et al. [7] showed that bile delays the healing of a liver wound, attributable to the fibrolytic or cytotoxic effects of bile. Bile can therefore cause a weakening of suture lines or sites of surgical clips in vessels. The presence of an infection is another contributing factor for the development of the hepatic artery aneurysm [8]. The most likely cause in our patient was a combination of an infection and a traumatic injury. The treatment of a hepatic artery aneurysm is an emergency because the patient may exsanguinate from a rupture at any time. Early recognition is a key to the management. Patients with hematemesis or melena following the laparoscopic cholecystectomy should have an urgent endoscopy, and if no cause is identified, an abdominal CT and hepatic angiography should be performed. Definitive treatment with radiologic embolization is the treatment of choice for HAP, although some reports of conservative management have been recorded [9]. In our case, the stenting of the replaced right hepatic artery and gel-foam embolization of the left hepatic artery were performed.

When a patient presents with massive GI bleeding, a climbing total bilirubin level and recent hepatobiliary manipulation or intervention, a high index of suspicion is always needed [10].

The added complexity in our patient was the presence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, the development of a left HAP in the presence of a thrombosed replaced right hepatic artery that was stented and finally, bleeding from the left HAP, which stopped with gel-foam embolization.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by NSTIP strategic technologies program number 11-MED1910-02 in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.