-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David Wallace, Dhilanthy Arul, Sudhanshu Chitale, Synchronous tumours of the breast and bladder, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2014, Issue 7, July 2014, rju066, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju066

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The presentation of synchronous primary tumours is rare and presents a difficult diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to primary care clinicians and hospital specialists. Increased life expectancy, improved radiological and biochemical investigation and more rigorous pre- and postoperative evaluation will lead to an increasing clinical trend for both metachronous and synchronous primary neoplasms. We report on a case of synchronous bladder and breast cancer in an elderly woman. We detail our investigation and management of the patient, review the literature and suggest the possible causative factors for the association of these synchronous tumours. We also highlight the extent of multiple primary cancers and discuss the diagnostic, treatment and preventative strategies for metachronous and synchronous primary tumours.

INTRODUCTION

The presentation of two simultaneous primary tumours is rare [1]. In the paper we report on an 82-year-old female who was diagnosed with primary breast and bladder cancer. We review the literature on multiple primary cancers (MPC) and discuss the diagnostic and treatment challenges of metachronous and synchronous breast and bladder cancer.

CASE REPORT

An 82-year-old female with known metastatic lobular breast cancer presented to a urology outpatient clinic with an incidental finding of a bladder mass at the left vesicoureteric junction (VUJ, Fig. 1). The bladder lesion had originally been identified on a surveillance computed tomography scan and was associated with left-sided hydronephrosis (Fig. 1).

Symptomatically the patient described a recent history of dysuria which had been treated unsuccessfully by the General Practitioner with a 3-day course of nitrofurantoin. There was no history of macroscopic haematuria. Urine dip at the time of clinic was positive for leucocytes and nitrates and further culture identified a significant growth of Staphylococcus aureus sensitive to penicillin. Renal function confirmed previous chronic kidney disease attributable to hypertension. A previous history of smoking that ceased 40 years ago was the only environmental risk factor identified.

Following discussion at a urological multi-disciplinary team (MDT) meeting, flexible cystoscopy was performed. This confirmed a 4 cm solid lesion on the left side of the bladder base with surface necrosis. Neither ureteric orifice could be identified. Two sub-centimetre satellite lesions were also noted on the right lateral wall of the bladder. Suspecting either primary urothelial cancer or adenocarcinomatous metastatic breast deposits a rigid cystoscopy, transurethral resection of bladder tumour and biopsies were scheduled.

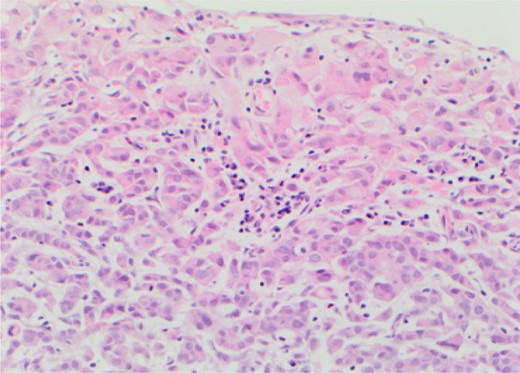

Rigid cystoscopy identified bullous oedema surrounding the 4–5 cm solid tumour that covered the entire bladder base. It had typical endoscopic appearance of a transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). Only after complete resection were the ureteric orifices identified with both showing good signs of peristalsis and efflux negating the need for stenting. Loop biopsies were taken to completely resect the satellite lesions on the right wall which had appearances atypical of a TCC and tissue was sent separately for histological diagnosis (Fig. 2). A 22 Fr catheter remained in situ until post-operative renal function stabilized and the patient was discharged awaiting histological diagnosis.

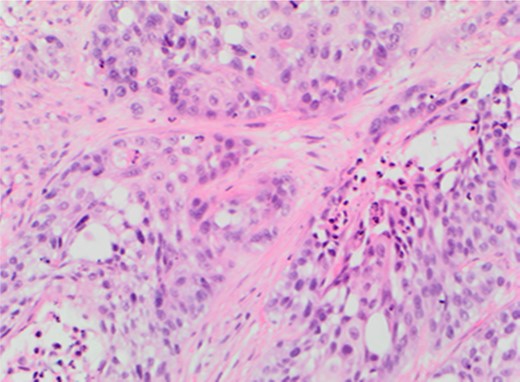

Metastatic lobular carcinoma of the breast identified on right wall of bladder.

The histopathological analysis identified two distinct malignant entities. The solid tumour at the base of bladder was confirmed as muscle invasive bladder cancer (G3pT2) whilst the satellite lesion showed features suggestive of metastatic lobular carcinoma of the breast. Following discussion at both urological and breast MDTs palliative chemotherapy was administered to address the metastatic breast cancer whilst palliative radiotherapy was used to contain the primary bladder cancer.

DISCUSSION

Whilst the incidence of patients developing MPC is increasing, the presentation of synchronous primary tumours remains rare [1, 2]. We have found only one other study that has documented a simultaneous presentation of primary urological and breast cancer [1] whilst a few others have described a metachronous association [2, 3].

Genetic pre-disposition through the identification of genes common to different organ tumours has been postulated as a cause for MPC [1, 4]. UROC28 is a gene that has been found in bladder, breast and prostate tumours leading to the theory that having a primary tumour might be a risk factor for developing another one, either synchronously or metachronously [1, 4]. Other theories include accumulation of free radicals and subsequent mistakes in DNA replication and reduced function of lipid laden macrophages leading to impaired host immune surveillance [1].

Environmental and demographic risk factors must also be considered [1]. Patients suffering specifically from primary breast cancer are at an increased risk of a secondary tumour in the female genitals and endocrine systems [2]. Obesity, tobacco and young age were all postulated as potential shared risk factors for this association [2]. Similarly, primary bladder cancer is associated with suffering subsequent malignancy in the genitals and respiratory system [2]. Tobacco is a shared risk factor for both bladder and lung cancer whilst topographic proximity could potentially explain the relationship between bladder cancer and subsequent genital malignancy [2].

There was no familial history of breast or urothelial cancer and our patient was not clinically obese. Often secondary and potentially simultaneous malignancies can be attributed to the first tumour treatment [1, 2]; however, there is no reported evidence to suggest that primary endocrine therapy for lobular breast cancer increases the risk of TCC of the bladder.

The increased detection of MPC and potentially of synchronous tumours can be attributed to increased use of more advanced diagnostic technique, in particular radiology, the introduction of screening practices and more rigorous oncological surveillance and peri-operative evaluation [1, 2].

There is no consensus on treatment recommendations for synchronous tumours. The opinion of most urologists in a questionnaire-based survey was that they would prefer to perform the tumour resections simultaneously if logistically and topographically feasible [1]. The only caveat was if one tumour was more aggressive than the other resection of the more aggressive tumour was prioritized [1]. Modification of behavioural risk factors and necessary lifestyle changes as a primary prevention to MPC has also been supported [2].

The index of suspicion for potential simultaneous primary malignancies must be heightened in clinicians. This is displayed in our case report where lesions on the base of the bladder and right lateral wall were not assumed to be of the same histological subtype and separate biopsies were taken and submitted for histopathological diagnosis.

Smoking was the only causative risk factor we could identify to explain the synchronous bladder and breast tumours. Other potential explanations for the development and identification of synchronous tumours include increased life expectancy, improved screening practices, increased exposure to environmental causative agents and genetic pre-disposition.

Treatment of synchronous tumours is dependent on the tumour's histological sub-type, location and progression. The surgical preference is for resection of both tumours simultaneously whilst modification of behavioural risk factors may prevent the occurrence of MPC.