-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Niloy Das, Nicholas R. Plummer, Hassan Raja, Ashok Vashist, What to do with a non-rolling stone? Surgical on-table dilemma in large bowel obstruction due to an impacted gallstone, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2014, Issue 7, July 2014, rju042, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju042

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present a rare case of large bowel obstruction secondary to colonic gallstones in a frail nonagenarian. Uniquely, the stone was impacted in the descending colon-sigmoid junction, in the absence of underlying bowel pathology distal to the stone. In light of worsening pain and distension after failed endoscopic treatment, the patient was treated with an emergency laparotomy. After an on-table dilemma, a proximal defunctioning loop colostomy was fashioned and the stone left in situ, with the eventual fate of the stone currently undecided. We also discuss alternative treatment options and explain the thought processes that lead to our decision.

INTRODUCTION

Gallstone ileus causing small bowel obstruction is a well-document phenomenon; however, gallstones causing large bowel obstruction are much rarer and almost always secondary to existing bowel pathology. We report what we believe to be the first case of large bowel obstruction caused by an impacted gallstone without primary pathology distal to the stone and discuss potential management options from the literature to rationalize our choice of a defunctioning loop colostomy with the stone left in situ.

CASE REPORT

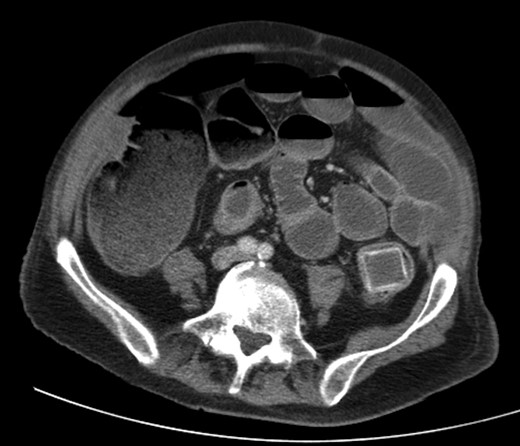

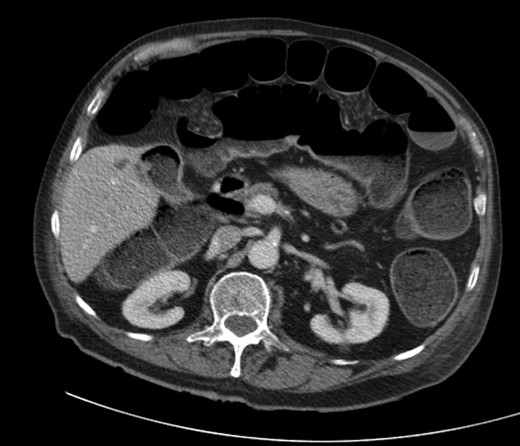

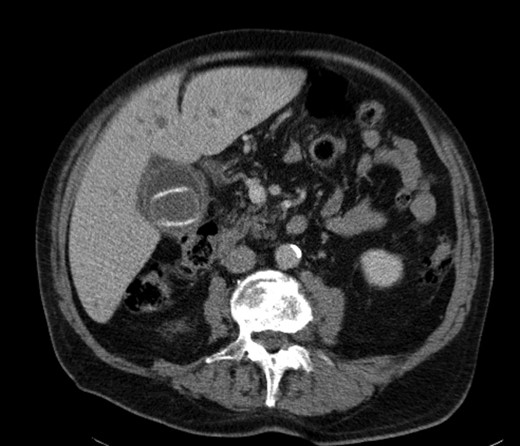

A 92-year male, with no significant co-morbidities apart from peptic ulcers, was admitted with 6 days of obstination. On examination he was dehydrated, with a hugely distended abdomen but no signs of peritonitis. Blood showed features of dehydration and plain abdominal X-ray demonstrated both small and large bowel dilatation, but no obvious causal pathology. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan revealed a 2.5-cm partially calcified gallstone impacted at the descending colon-sigmoid junction (Fig. 1). There was no stricture or diverticular disease distal to the stone. A cholecysto-colic fistula could be seen (Fig. 2), with a further smaller gallstone in the caecum (Fig. 3). The offending gallstone could be seen incidentally in the gallbladder on imaging 3 years previously (Fig. 4).

Large gallstone impacted in the descending colon-sigmoid junction, causing large bowel obstruction proximally.

Cholecysto-colic fistula, with a thick-walled, dilated, gallbladder.

CT reconstruction showing the impacted gallstone and a smaller incidental gallstone in the caecum.

The offending gallstone as an incidental finding 3 years previously.

The patient was initially resuscitated, although he could not tolerate an naso-gastric tube. Retrieval of the stone was first attempted via flexible sigmoidoscopy. This failed due to a large amount of faecal matter distal to the stone, despite several phosphate enemas. In light of worsening abdominal distension and pain, the patient underwent a lower midline laparotomy where the hugely dilated small bowel was decompressed via the stomach, the descending colon mobilized and the diagnosis confirmed. There was indeed no primary pathology distal to stone; however, the stone could not be disimpacted, and the overlying colonic wall was viable with no evidence of ischaemia. Considering the patient's age and physiological reserve, the duration of large bowel obstruction, high morbidity and mortality associated with emergency surgery, and the fear of leak following a colotomy, an on-table decision was made to perform a proximal defunctioning loop transverse colostomy to relieve the obstruction. The cholecysto-colic fistula was left untouched, and the impacted stone left in situ.

The patient made an uneventful but slow recovery with resolution of obstruction. He was discharged home and is managing his stoma well. He will be brought back to the clinic to discuss the options with regard to removal of stone and reversal of his colostomy.

DISCUSSION

Gallstone ileus is not an uncommon phenomenon [1]; however, large bowel obstruction due to stone impaction is rarely seen due to the large calibre of the colon, with few case reports in the literature [2, 3]. The site of impaction is usually the sigmoid [3, 4], with retention of the stone as a result of a stricture from diverticular disease or previous radiotherapy [5]. The stone is thought to enter the colon via a cholecysto-colic fistula, developing during a bout of acute cholecystitis affecting the hepatic flexure [6]. The gallstone should be at least 2–2.5 cm in diameter to cause obstruction [1].

Cases usually present with features of large bowel obstruction; however, colonic gallstones may also present atypically with non-specific symptoms such as diarrhoea, cholangitis or bleeding from the fistula tract. The diagnosis is best made on computed tomography (CT).

A trial of conservative treatment may be attempted [7], and colonoscopy with and without lithotripsy has been successful in relieving obstruction [8]; however, surgery may be needed if the stone cannot be retrieved and will not pass spontaneously. There is no definite consensus as to how a gallstone impacted in the colon should be treated. The options are a combination procedure of enterolithotomy, cholecystectomy and fistulectomy, or enterolithotomy alone with or without a covering loop colostomy to resolve the immediate obstruction [2, 3]. The former leads to relief of the obstruction as well as preventing further stone formation and episodes of cholangitis; however, as these patients are invariably elderly and bearing significant co-morbidities, a minimalistic approach is often preferable.

In our case a laparotomy was undertaken as endoscopy failed and the patient's pain and distension continued to worsen. At laparotomy the small bowel was decompressed to view the colon and to rule out further contributing pathology. A defunctioning transverse loop colostomy was performed without removing the stone to avert the immediate crisis, while minimizing morbidity and mortality. In retrospect, we could have considered trephine defunctioning loop colostomy alone. This would have hastened patients’ post-operative recovery, while resulting in a similar functional outcome.

We believe this to be the first instance that an impacted gallstone has been left in situ post-operatively with a proximal loop colostomy used for symptomatic relief. There are various options now for retrieval of the stone, should this be necessary. The gallstone could be accessed directly via the colostomy or anus, and it may be possible to use lithotripsy to shatter and remove the stone [9] without resorting to surgery. On the other hand, it could be left alone, as although fears remain that such a stone might erode through the wall or cause a localized abscess, decompression of the bowel has significantly reduced the chance of pressure necrosis and related complications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Punnya Ghosh, Ravi Date and Alka Jadav for advice regarding patient management and reviewing the manuscript; Matt Briggs for the 3D CT reconstructions.