-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Pélagie Sikiminywa-Kambale, Anass Anaye, Daniel Roulet, Edgardo Pezzetta, Internal hernia through the foramen of Winslow: a diagnosis to consider in moderate epigastric pain, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2014, Issue 6, June 2014, rju065, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju065

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Herniation through the foramen of Winslow is a rare condition that can lead to a delayed diagnosis and treatment with a high mortality rate. In most reported cases, patients present to the emergency department with symptoms suggesting intestinal obstruction or with sudden and severe pain in the upper abdomen. Symptoms are non-specific. Clinical diagnosis may be difficult or even missed. The widespread availability of cross-sectional imaging can improve the percentage of correct preoperative diagnosis. We report a case of a caecal and right colic herniation through the foramen of Winslow found incidentally on abdominal computed tomography in a patient presenting with mild epigastric pain.

INTRODUCTION

Hernias through the foramen of Winslow are rare and constitute only 8% of internal hernias. The rate of preoperative diagnosis has been reported to be <10% of the intraoperatively confirmed cases [1]. A delay in diagnosis and treatment is often observed and may be responsible for the high mortality rate of up to 49% associated with this hernia type. Internal hernia is often revealed by intestinal obstruction associated with non-viable bowel at the time of operation [2].

We present a case of a patient with moderate epigastric pain in whom a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed the unexpected finding of right colonic herniation through the foramen of Winslow.

CASE REPORT

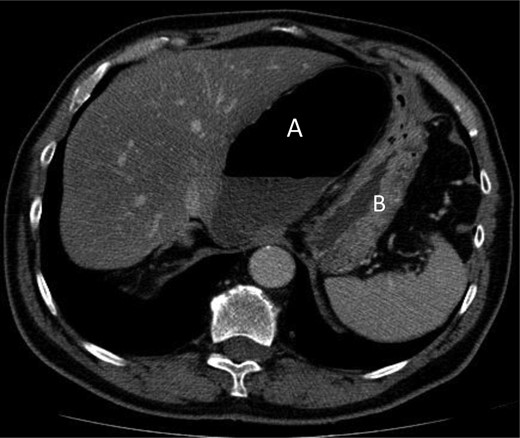

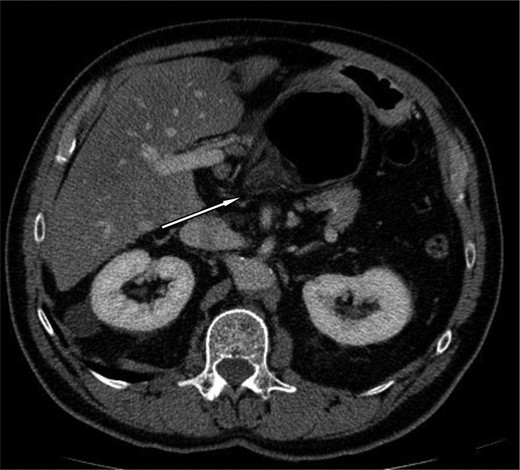

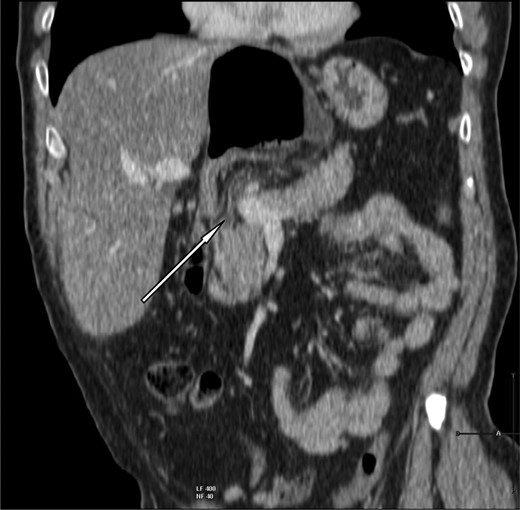

A 69-year-old patient presented to our emergency room with progressive dull abdominal pain and distension without nausea, vomiting or change in bowel habits. Physical examination showed pain with moderate guarding in the right upper and lower quadrants. A plain abdominal X-ray and a CT scan were performed. Radiological findings suggested the diagnosis of an internal hernia through the epiploic foramen and containing the right colon with important distension of the caecum (Fig. 1). Surgical exploration was then performed using an open approach. At laparotomy, we found an internal herniation of the caecum and the entire ascending colon through the foramen of Winslow (Figs 2 and 3). After hernia reduction, multiple patchy areas of caecal necrosis were observed (Fig. 4). A formal right hemi-colectomy was therefore performed. The postoperative recovery was uneventful.

Axial section through upper abdomen showing distended caecum with air-fluid level (A) with the displacement of the stomach (B) laterally.

Axial section demonstrating the hernia through the foramen of Winslow.

Coronal slice showing herniation of right colon through the foramen of Winslow.

The herniated segment after reduction, with areas of necrosis.

DISCUSSION

Foramen of Winslow hernia can be defined as peculiar variant of internal abdominal hernia, since it is a normal peritoneal orifice kept closed by normal intra-abdominal pressure that may be permeated by the intra-abdominal viscera [3].

There are multiple anatomical abnormalities reported as possible predisposing factors for a visceral herniation through this foramen [4]: (i) abnormally enlarged foramen; (ii) the presence of an unusually long small-bowel mesentery or persistence of the ascending mesocolon; (iii) an elongated right hepatic lobe, which could be directing the mobile intestinal loop into the foramen; (iv) a lack of fusion between caecum or ascending colon to the parietal peritoneum; (v) a defect in the gastrohepatic ligament, (vi) incomplete intestinal rotations or malrotation.

Since the first report in 1834 by Blandin in autopsies, <200 cases of foramen of Winslow hernia have been reported in the medical literature [1].

Symptoms are usually related to bowel obstruction. The typical presentation is an acute severe mid-epigastric pain associated with nausea and vomiting. The severity of the pain is related to the presence of bowel strangulation with subsequent necrosis. In some very particular cases, the internal hernia through the Winslow hiatus is revealed by an obstructive jaundice due to direct compression of the hepatic pedicle [2].

Clinical examination is non-specific and laboratory findings are rarely helpful.

The key to diagnosis relies on prompt radiologic studies and the CT scan is nowadays considered the technique of choice. Various, more or less specific findings have been reported, such as an air-fluid collection in the lesser sac or signs of small bowel obstruction associated with the presence of mesenteric vessels stretching anterior to the inferior vena cava and posterior to the portal vein; the absence of the ascending colon in the right gutter and an antero-lateral displacement of the stomach [3].

The treatment invariably requires urgent surgery, and even if symptoms are limited as in our case, it should be considered in order to assess intestinal viability because of the risk of intestinal strangulation.

Usually open surgery is performed. Only a few cases of laparoscopic hernia management have been reported [5].

Treatment is based on careful inspection with subsequent hernial reduction that is frequently possible with simple and gentle traction. Occasionally, this can be difficult; in these situations the gastrocolic or gastrohepatic ligaments must be opened or, alternatively, a wide Kocher manoeuvre performed. In the case of massive colonic dilatation a colotomy for decompression with a suction device can be useful [5, 6]. In the case of overt intestinal necrosis an adequate resection is obviously mandatory; nevertheless there is no clear and established consensus on surgical management when the herniated contents are grossly viable. Some surgeons report right colonic fixation or caecopexy to the lateral wall, whereas others advocate right colectomy especially when there is a lack of fusion between caecum or ascending colon to the parietal peritoneum in order to avoid subsequent volvulus [5].

Furthermore, in order to prevent recurrent herniation, some surgeons decide to definitively close the foramen of Winslow. This option can however lead to meaningful complications such as accretions and/or portal vein thrombosis. Thus, leaving the foramen open may be justifiable since the inflammatory post-operative adhesions will most often obliterate the foramen entrance with no evidence of recurrent herniation [3, 6].