-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Vitali Azouz, Jeremy D. Simmons, Georges S. Abourjaily, Immediate postoperative parastomal end sigmoid hernia resulting in evisceration and strangulation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2014, Issue 5, May 2014, rju047, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju047

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Parastomal evisceration is a very rare complication occurring after stoma formation. We report the case of this complication which occurred within 3 days status post end sigmoid colostomy in a 69-year-old male who initially presented with perianal infection–severe necrotizing fasciitis. This case highlights the significance of the size of a stomatal aperture and should remind general surgeons of the one of dangerous complications indicated by a stomatal aperture that is just a centimeter larger than the accepted ideal size.

INTRODUCTION

While the very common complication of parastomal hernia following stoma formation has been well studied and documented in the literature, the rare complication of parastomal evisceration has been featured in just four case reports [1–4]. We present this case to bring new attention to this rare and relatively undocumented complication.

CASE REPORT

A 69-year-old male presented to the emergency room with findings of a necrotizing perianal fasciitis. His past medical history was significant for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, partial gastric outlet obstruction, alcohol abuse and a 50 pack/year smoking history. He was initially brought to the operating room 4 days later for soft tissue debridement and diverting end sigmoid colostomy.

After a midline laparotomy incision was made. The distal sigmoid colon was identified and divided with a GIA 75 stapler leaving a distal rectosigmoid pouch. An incision was made in the left lower quadrant. The proximal end of sigmoid colon was then brought through the cruciate facial defect which had been dilated to three finger widths. The distal end was stapled and left as a distal sigmoid stump. The stoma was matured in Brooke fashion using 3-0 vicryl sutures. Sutures were placed at the level of the skin and not placed at the level of the fascia. The patient was then transferred to the Surgical Intensive Care Unit (SICU) in stable condition.

On postoperative Day 1, the patient′s perianal wound was found to have purulent discharge and swabs revealed gram-positive cocci in chains. The patient returned to the operative room (OR) for additional debridement. On postoperative Day 2, the patient′s white blood cell count improved from 17 to 15, and tissue culture revealed alpha hemolytic streptococcus. The patient′s wounds appeared to be clean, dressings were changed and the patient was advanced to a regular diet and transferred to the ward.

After the original surgery and interval debridement, the patient was transferred to the floor. His wound cultures grew Streptococcus viridians sensitive to cefazolin and his antibiotic regimen was narrowed.

On postoperative Day 3, the patient began having nausea and vomiting. On examination, the patient was found to have his colostomy bag filled with multiple loops of small bowel (Fig. 1). At this point he was diagnosed with an evisceration and was taken back to the operating room emergently for reduction and repair.

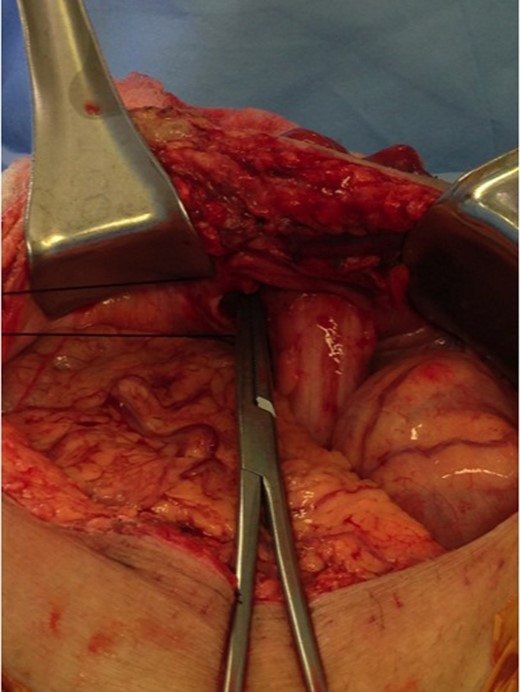

In the OR, the stoma bag was removed and illustrated parastomal fascial dehiscence and evisceration (Figs. 2 and 3). The midline incision was reopened and 100 cm of compromised small bowel was resected with stapled anastomosis. The parastomal defect was then visualized (Fig. 4), repaired with running 2-0 vicryl, and the abdominal closure was closed with retention nylon sutures and looped PDS in running fashion through the fascia. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was postoperatively transferred to the SICU. The patient was then transferred to a regular surgical ward and discharged to extended care for follow-up anticipating ostomy reversal after healing of perineal wound.

DISCUSSION

As evident by this case, a colostomy is not always a simple and quick procedure. Possible serious complication may occur [1–5]. A colostomy must be undertaken meticulously and not simply delegated to an intern or junior surgical resident. Like all major surgeries, surgeons must be aware of the complications no matter their prevalence.