-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kit Brogan, Steve Nicol, Flexor digitorum profundus entrapment in paediatric forearm fractures, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2014, Issue 5, May 2014, rju038, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju038

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Entrapment of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) is a recognized complication of paediatric both-bone forearm fractures. Although a rare complication, it is usually missed at the time of initial fracture management resulting in the need for corrective surgery. An attempted closed manipulation followed by immediate surgical correction of FDP entrapment in our hospital prompted a review of the evidence on this underreported problem. A comprehensive English language literature search was performed using Embase, Medline and Pubmed. Twenty cases have been reported in the literature and all were diagnosed post-operatively (range 2 days–16 years). Eighteen cases (90%) required surgical correction. Five cases (25%) were initially diagnosed as mild Volkmann's contracture yet at surgery no case was found to have evidence of previous muscle ischaemia. Although subclinical or mild Volkmann's ischaemic contracture is a recognized complication of closed forearm fracture, this report highlights the importance of considering a diagnosis of muscle entrapment in cases of flexion contracture.

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of paediatric forearm fractures is increasing worldwide despite the falling overall injury rate [1]. Flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) entrapment in forearm fractures is a recognized complication but in the 20 cases reported in the literature so far the recognition of the problem occurred following fracture resolution [2–8]. We report a case of entrapment of the ring finger FDP at the musculotendinous junction in a 12-year-old male with a both-bone greenstick forearm fracture, and review the literature surrounding this unusual complication.

CASE REPORT

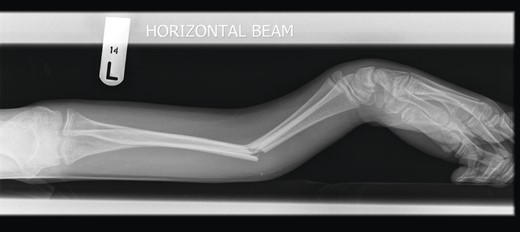

A 12-year-old male patient sustained a closed midshaft both-bone forearm fracture of their non-dominant arm from a fall on a trampoline (Figs 1 and 2). Anatomical reduction was achieved with a manipulation under anaesthesia (MUA), but it was noticed that there was a mechanical block to extension of the ring finger. The radius and ulna were therefore approached through separate incisions and it was discovered that the FDP was entrapped at the ulna fracture at the level of the musculotendinous junction. Following release the fingers regained a full range of motion and the patient went on to heal without further complication (Figs 3 and 4).

Pre-operative lateral radiograph showing dorsally angulated both-bone forearm greenstick fracture.

Pre-operative anteroposterior (AP) radiograph showing level of fracture at the junction of proximal two-thirds and distal one-third.

Three months post-operative lateral radiograph showing radiological union.

DISCUSSION

The origin of the ringer finger FDP fibres are almost exclusively from the volar aspect of the ulnar, whereas the origin of the fibres going to the index and middle fingers is the interosseous membrane [7]. The fibres to the little finger do arise from the ulna but from the medial side with a fibrous attachment that is more linear, whereas the ring finger origin is over a wide surface area [7].

Of the 20 reported cases, all were diagnosed at follow-up, ranging from 2 days to 16 years [2–8]. Two patients (10%) [4] were successfully managed within a few days of the initial MUA by repeated MUA. However, 18 (90%) eventually required surgical intervention with exploration of the ulna fracture following failed conservative management with hand therapy. In cases of early surgical intervention (days) muscle was released from the fracture site but if the diagnosis was delayed scar tissue was encountered at the fracture site, which was released subperiosteally. A pre-operative diagnosis of mild Volkmann's ischaemic contracture made in 5 (25%) yet at surgery none of the 20 patients had any evidence of muscle necrosis.

There was one report of FDP entrapment with flexible intramedullary nailing [3]. Cullen et al. [9] has described the complications that can occur with intramedullary fixation of these injuries, including muscle entrapment, thereby making it essential to examine the fingers following the use of intramedullary nails. Radiographic union of the fracture associated with ulna cortical defect [3] and lack of active finger extension is pathognomonic of entrapment at the fracture site and such cases should be explored surgically.

Sub-clinical or mild Volkmann's ischaemic contracture is a recognized complication of closed forearm and other fractures [8]. However, this report highlights the importance of considering a diagnosis of muscle entrapment in cases of flexion contracture, particularly in the absence of other signs or symptoms of compartment syndrome. The inability to extend the fingers following closed reduction should be regarded as a definite indication to surgically explore the fracture site. This and other case studies support the idea that FDP is more likely to be entrapped at the ulna and the level can be surprisingly proximal. In our own experience the problem was recognized following closed manipulation and was surgically corrected immediately. However, the literature is consistent in that in all cases there was either no mention of finger range of motion post-operatively or that the problem was not recognized until follow-up. This may be due to a lack of awareness of entrapment as a potential complication of midshaft forearm fractures. To our knowledge, this is the first case report of surgical exploration at the time of the initial manipulation to rectify entrapment.

Flexion contractures secondary to FDP entrapment can be avoided, first by awareness of this potential complication, and secondly by careful examination of the fingers after closed treatment of a forearm fracture. Following closed manipulation or intramedullary fixation of forearm fractures, it is essential to document examination of the ipsilateral fingers in order to exclude entrapment. If entrapment is diagnosed then it should be managed surgically as conservative measures have not been shown to be effective. Surgery can be expected to yield excellent results even in cases of delayed diagnosis, but failure to make the diagnosis may lead to chronic morbidity.

Level of evidence: Levels III and IV.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There are no conflicting interests and there has been no financial support for this work.