-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David Bodansky, Robert Jones, Olga N. Tucker, An alternative option in the management of blunt splenic injury, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2013, Issue 8, August 2013, rjt061, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjt061

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Splenic injury is a preventable cause of mortality following blunt trauma. The majority of splenic injuries can be managed conservatively. Laparotomy is indicated in the haemodynamically unstable patient, or those with other intra-abdominal injuries requiring surgery. Angio-embolization can be used to achieve haemostasis and preserve splenic parenchyma. The expertise and experience of the multidisciplinary trauma team and resources of the receiving facility are critical in determining the optimal management approach. We present a patient with a successful outcome following selective angio-embolization for ongoing bleeding from a Grade 4 splenic injury.

INTRODUCTION

Blunt splenic trauma can result in life-threatening haemorrhage, and the majority can be managed conservatively. Interventional radiology is increasingly employed for haemostasis and organ function preservation.

CASE REPORT

A 27-year-old passenger was ejected from a car following a high-speed collision. On arrival at the emergency department, she was normotensive, tachycardiac, complaining of abdominal pain. Examination revealed tenderness along the left lower chest wall and upper abdomen, with multiple facial and anterior leg lacerations. She had a persistent tachycardia which responded to intravenous crystalloids and two units of packed red cells.

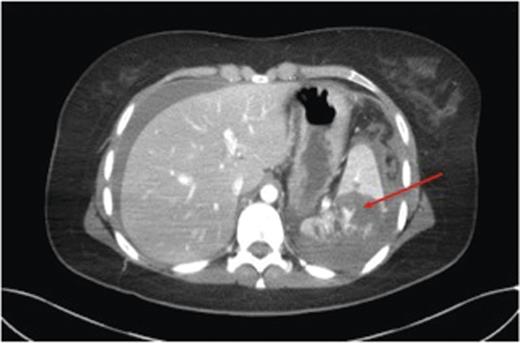

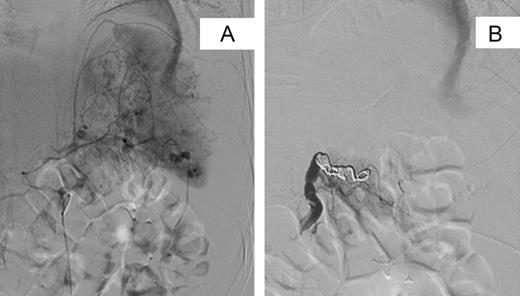

An urgent contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan of head, neck, thorax, abdomen and pelvis was performed, demonstrating a Grade 4/5 splenic laceration with several foci of active haemorrhage and a large volume of peri-splenic free fluid consistent with blood with no other intra-abdominal injuries (Fig. 1). Following review, a decision was taken to perform angiography with a view to selective angio-embolization as the patient remained haemodynamically stable. Contrast angiography demonstrated multiple small pseudoaneurysms within the peripheral branches of the splenic artery with active contrast extravasation. The splenic artery was selectively catheterized and embolized at its mid-point with several coils (Fig. 2). At the end of the procedure, collaterals were seen supplying the residual non-injured splenic tissue, with the absence of active contrast extravasation. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for continuous haemodynamic monitoring for 36 h. Appropriate additional plain facial and long limb imaging was performed when stable, and no additional injuries were noted. She made an uneventful recovery and was discharged 9 days following admission. An abdominal ultrasound scan, 6 weeks later, confirmed almost complete resolution of the peri-splenic haematoma.

CECT demonstrating a grade 4 splenic injury with contrast extravasation suggesting active haemorrhage (arrow).

Selective digital subtraction angiography pre- and post-splenic artery embolization. (A) Pre-embolization image demonstrating multiple focal areas of haemorrhage. (B) Post-embolization image demonstrating coils within the main splenic artery with early filling of collateral vessels.

DISCUSSION

In a haemodynamically unstable patient with blunt abdominal trauma, the goal is identification of the source and control of ongoing haemorrhage. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) is available in major emergency departments to detect free fluid in the upper quadrants of the abdomen, pelvis and pericardial sac. Although rapid, non-invasive and reproducible, assessment of the retroperitoneal cavity by FAST is limited with reported false-negative rates of 20–59% [1]. Whole-body CECT scanning has become the gold standard diagnostic approach in blunt polytrauma, with resultant early intervention leading to greater survival rates [2]. Using CECT solid intra-abdominal organ injury following blunt abdominal trauma is graded using the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) scale (Table 1) [3]. Importantly, these grades do not account for ongoing haemorrhage or additional organ injury. In patients with active haemorrhage, CT angiography visualizes contrast extravasation associated with haematoma [4]. Recent advances in CECT imaging facilitate a whole-body scan in <20 s facilitating rapid assessment. The safe performance of a CECT is determined by the availability, ease of access and proximity of the CT to the patient [4].

| Grade . | Injury . | Description . |

|---|---|---|

| I | Laceration | Capsular tear, <1 cm parenchymal depth |

| II | Haematoma | Subcapsular, 10–50%, surface area |

| Intraparenchymal, <5 cm in diameter | ||

| Laceration | 1–3 cm parenchymal depth, which does not involve a trabecular vessel | |

| III | Haematoma | Subcapsular, >50% surface area or expanding; ruptured subcapsular or parenchymal haematoma |

| Intraparenchymal haematoma >5 cm or expanding | ||

| Laceration | >3 cm parenchymal depth or involving trabecular vessels | |

| IV | Laceration | Laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels producing major devascularization (>25% of spleen) |

| V | Laceration | Completely shattered spleen |

| Vascular | Hilar vascular injury which devascularizes spleen |

| Grade . | Injury . | Description . |

|---|---|---|

| I | Laceration | Capsular tear, <1 cm parenchymal depth |

| II | Haematoma | Subcapsular, 10–50%, surface area |

| Intraparenchymal, <5 cm in diameter | ||

| Laceration | 1–3 cm parenchymal depth, which does not involve a trabecular vessel | |

| III | Haematoma | Subcapsular, >50% surface area or expanding; ruptured subcapsular or parenchymal haematoma |

| Intraparenchymal haematoma >5 cm or expanding | ||

| Laceration | >3 cm parenchymal depth or involving trabecular vessels | |

| IV | Laceration | Laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels producing major devascularization (>25% of spleen) |

| V | Laceration | Completely shattered spleen |

| Vascular | Hilar vascular injury which devascularizes spleen |

| Grade . | Injury . | Description . |

|---|---|---|

| I | Laceration | Capsular tear, <1 cm parenchymal depth |

| II | Haematoma | Subcapsular, 10–50%, surface area |

| Intraparenchymal, <5 cm in diameter | ||

| Laceration | 1–3 cm parenchymal depth, which does not involve a trabecular vessel | |

| III | Haematoma | Subcapsular, >50% surface area or expanding; ruptured subcapsular or parenchymal haematoma |

| Intraparenchymal haematoma >5 cm or expanding | ||

| Laceration | >3 cm parenchymal depth or involving trabecular vessels | |

| IV | Laceration | Laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels producing major devascularization (>25% of spleen) |

| V | Laceration | Completely shattered spleen |

| Vascular | Hilar vascular injury which devascularizes spleen |

| Grade . | Injury . | Description . |

|---|---|---|

| I | Laceration | Capsular tear, <1 cm parenchymal depth |

| II | Haematoma | Subcapsular, 10–50%, surface area |

| Intraparenchymal, <5 cm in diameter | ||

| Laceration | 1–3 cm parenchymal depth, which does not involve a trabecular vessel | |

| III | Haematoma | Subcapsular, >50% surface area or expanding; ruptured subcapsular or parenchymal haematoma |

| Intraparenchymal haematoma >5 cm or expanding | ||

| Laceration | >3 cm parenchymal depth or involving trabecular vessels | |

| IV | Laceration | Laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels producing major devascularization (>25% of spleen) |

| V | Laceration | Completely shattered spleen |

| Vascular | Hilar vascular injury which devascularizes spleen |

The management of blunt splenic injury is determined by haemodynamic stability of the patient, and the presence or absence of other intra-abdominal injuries requiring surgical intervention. Options include conservative non-operative management (NOM) with frequent monitoring of clinical status. Other options include angiography and angioembolization, partial or complete splenectomy. Since the early 1980s, NOM of haemodynamically stable patients with blunt splenic injury has become the standard of care in paediatric and adult populations [5]. Successful outcome following NOM is reported as up to 97% of patients regardless of the grade of splenic injury [6]. However, significant blunt splenic injury can be associated with other intra-abdominal and/or extra-abdominal injuries in 7.5–69% [7]. Haemodynamically stable patients with low-grade splenic injury and minimal haemoperitoneum managed conservatively have a reported delayed splenectomy rate of 10% [8]. Emergency splenectomy provides definitive treatment but carries a small lifelong risk of postsplenectomy sepsis syndrome. Consequently, selective hepatic artery embolization is being increasingly employed in patients with confirmed active bleeding on CECT and/or selective hepatic angiography [9]. An on-call interventional radiological service is recommended in all level 1 trauma centres [4].

At angiography, haemostasis can be achieved using a range of approaches. Arterial occlusion with an inflatable balloon is rapid and simple, and can halt life-threatening blood loss. Stenting is indicated for disrupted vessels that may be difficult to gain access to at laparotomy or where vessels are tamponaded by surrounding haematoma when laparotomy may result in further haemorrhage and instability. Stenting can provide vessel wall support in traumatic pseudo-aneurysms and/or dissections. In addition, angio-embolization can also be used to arrest haemorrhage after unsuccessful laparotomy or in a patient who rebleeds after a period of stability following blunt abdominal trauma.

The choice of embolization agent depends on the durability of the occlusion required and the diameter of the affected blood vessel. In blunt abdominal trauma, haemorrhage arrest with transient occlusion is usually performed using a temporary occluding agent such as gel-foam. Alternatively, permanent agents including coils or glue can be considered. In unstable patients, a large catheter can be threaded swiftly into the main splenic artery and angio-embolization achieved. However, the optimal approach is catheter placement in close proximity to the bleeding site to minimize de-vascularization of remnant normal tissue to preserve organ function [9, 10]. A micro-catheter can be advanced creating a selective block even to a terminal arteriole. Complications of angio-embolization are uncommon occurring in ≤5% usually related to arterial access, inserting and advancing the catheter, or rarely the contrast material including anaphylaxis and nephropathy. Arterial inflow to non-target parenchyma may occur. Splenic necrosis can occur, causing pain and pyrexia with insufficient collateral vascular supply or following prolonged main vessel balloon occlusion [4]. However, collateral supply through the short gastric or pancreatic vessels reduces the risk of organ ischaemia. Post embolization syndrome, a triad of pain, pyrexia and nausea or vomiting is a rare complication [4].

Isolated blunt splenic trauma is uncommon. Laparotomy and splenectomy are indicated in the haemodynamically unstable patient or those with other intra-abdominal injuries requiring laparotomy. Increasingly selective splenic artery embolization is being employed in haemodynamically stable patients with evidence of ongoing haemorrhage on CECT to avoid the need for surgery and to preserve splenic parenchyma.