-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Laura J. Halliday, Management of a bilobed testicle in a 12-year-old boy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2013, Issue 12, December 2013, rjt112, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjt112

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A bilobed testicle is an extremely rare congenital malformation, with only five cases published to date. We present the case of a 12-year-old boy with a bilobed testicle. With so few cases available, much of what is known about the management of this condition is based on cases of polyorchidism and the complications associated with this, including malignancy and torsion. Whilst surgery may play a role in some patients, uncomplicated cases can be managed conservatively. There is no long-term data on the outcome of conservative management but we propose this patient can be discharged if no further changes are identified after 18 months.

INTRODUCTION

A bilobed testicle is an extremely rare congenital malformation. Five cases have been reported to date. This report is of a bilobed testicle in a 12-year-old boy, which presented as an atypical testicular mass. It is thought to be a variant of polyorchidism, which is associated with an increased risk of malignancy and testicular torsion. Due to the extremely rare nature of bilobed testes, it is important to report our findings and start to gather information on the long-term outcome of this condition.

CASE REPORT

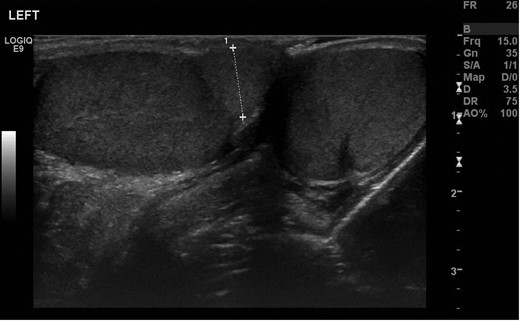

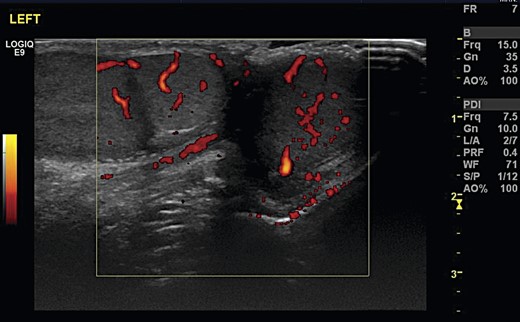

A 12-year-old boy was referred by his GP to the paediatric surgery clinic in a district general hospital with a 6-week history of a lump near the inferior pole of his left testicle. It was non-tender, non-erythematous and had not changed in size or consistency. He was otherwise fit and well, with no family history of urological disorders. On examination, his abdomen was soft and non-tender, with a normal right testis and right spermatic cord. A smooth well-defined lump was palpated on the inferior pole of the left testis. The rest of the testicle had a normal consistency with a normal left cord. Ultrasound demonstrated that both testicles were of a similar size, with normal vascularity and normal epididymi. The palpable lump corresponded to a well-defined 1-cm mass attached to the lower pole of the left testicle (Fig. 1). It had a similar echo pattern to the testicle with normal vascularity (Fig. 2), consistent with the finding of a bilobed testis.

Transverse ultrasonography of the scrotum. A mass is seen attached to the left testicle with the same echo pattern as the normal testicular tissue.

Transverse ultrasonography of the scrotum. A mass is seen attached to the left testicle with the same vascularity as surrounding testicular tissue.

The boy was reviewed 3 months later in outpatient clinic. The size of the lump was unchanged, although he now reported intermittent pain and swelling of the lump. He was referred to a consultant paediatric urologist and his testicle rescanned 6 months after his initial presentation. He was asymptomatic at this time. The ultrasound findings were unchanged and confirmed normal testicular architecture. He will be reviewed again in 12 months, with a view to discharging him if no further changes are seen.

DISCUSSION

Of the five previously reported cases of a bilobed testicle, four are in children aged from 3 to 13 [1–4] with the other occurring in a 30-year-old man who had been symptomatic for 10 years [5]. A bilobed testicle is thought to represent an incomplete division of the genital ridge by peritoneal bands during the development of the testis from 6 weeks of embryological life. Polyorchidism occurs with the complete division of the genital ridge. Ultrasound and MRI imaging of polyorchidism have demonstrated that the combined length of a supernumerary and ipsilateral testicle are the same as the contralateral testicle [6], supporting this theory.

Approximately 100 cases of polyorchidism have been reported [7]. Due to the larger number of case reports in comparison with a bilobed testicle and the presumed similar aetiology, we are reliant on the literature on polyorchidism when considering the management of a bilobed testicle. The risk of malignancy in a supernumerary testicle is reported between 5.7 and 7% [5], in comparison with 6 in 100 000 in the general population and 24 in 100 000 in cryptorchidism. There are no published cases to date of malignancy associated with a bilobed testicle and the reported cases of malignancy have occurred when the supernumerary testicle was found in a non-scrotal position [7]. Consequently, whilst an increased risk of malignancy is possible, the evidence is insufficient to advocate surgical management.

A testicular tumour should be considered as a differential diagnosis of any scrotal mass. In view of the normal testicular architecture and vascularity on ultrasound, we excluded a tumour in our patient due to the high sensitivity of ultrasound [8]. Consequently, tumour markers such as alpha-fetoprotein and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin were not measured. Spermatogenesis is normal in 50% of supernumerary testicles [6] and it is likely that this figure is higher for bilobed testicles. A growing number of case reports suggest that conservative management with regular follow-up and imaging is appropriate for polyorchidism with normal echotexture on ultrasound and uncomplicated cases of bilobed testis [1, 2, 5–7].

A review published in 2004 found the risk of testicular torsion of a supernumerary testicle to be 15% [6], in comparison with 0.025% of the general population and 0.25% in cryptorchidism. Of the five reported cases of bilobed testis, one case presented with torsion resulting in orchidectomy [2]. Patients and their families should be made aware of the increased risk of torsion. They must know the signs and symptoms of torsion and be encouraged to present early if it is suspected. Unlike cryptorchidism, surgery is not otherwise required for a bilobed testicle and therefore orchidopexy is not appropriate for uncomplicated cases. In our case, the child reported intermittent pain and swelling at his first follow-up appointment. However, he was asymptomatic when examined with no ultrasound changes and so it was not felt that orchidopexy was indicated.

There is no long-term data on the outcome of a bilobed testicle. Regular hospital appointments can produce unnecessary distress and concern for the patient and their family. If no changes are seen in a further 12 months, our patient will be discharged to primary care. Self-examination of the testicle may be challenging due to the distorted anatomy but should be advocated to detect early changes. Ultrasound must be undertaken promptly if there is any concern about changes to the testicle. Monitoring tumour markers may be appropriate in non-scrotal polyorchidism due to the significantly increased risk of malignancy. As the current literature does not provide strong evidence of malignancy associated with bilobed testis, it should not be advocated for this condition.

Conservative management appears to be appropriate in uncomplicated cases such as the one we present. It is unclear how the risk of torsion and malignancy in polyorchidism is applicable to a bilobed testicle. The risk of unnecessary surgery needs to be balanced against the risk of these serious complications. It is important that any long-term complications are reported to further our knowledge of this extremely rare condition.