-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

M. Rastrelli, N. Passuello, D. Cecchin, U. Basso, A.L. Tosi, C.R. Rossi, Metastatic malignant soft tissue myoepithelioma: a case report showing complete response after locoregional and systemic therapy, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2013, Issue 12, December 2013, rjt109, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjt109

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We report on the case of a 61-year-old man with a soft tissue malignant myoepithelioma of the second toe of the right foot. After removal of the primary tumor, the patient developed in-transit metastases of the limb that we later treated with limb perfusion, using extracorporeal circulation with complete response. Following the appearance of lymph node metastases, the patient underwent inguinal, iliac and obturator lymphadenectomy. Subsequent pelvis metastases were treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy, with complete response. Currently, after 3 years, the patient is alive and no evidence of any residual disease is apparent.

INTRODUCTION

Soft tissue malignant myoepithelioma (STMM) is an extremely rare disease and very few cases have been reported in the literature [1–3]. The first described STMM was a retroperitoneal lesion reported by Burke in 1995 [4]. In 2002, STMM was incorporated into the World health Organization Classification and in 2003 Fletcher published a series of 101 cases in which he proposed the anatomopathological criteria for malignancy [5]. The survival rate that can be observed from a review of the literature is ∼24 months with a follow-up range between 4 months and 9 years. These tumors are described with a considerable amount of local recurrence [1, 5] (30%) and are able to give lymph node metastasis (∼11.8%) and distant, especially pulmonary, metastasis [2, 3, 5] (∼15%). In general, a surgical excision with free margins [1] and the absence of moderate/severe cellular atypia after histological examination [6] have been identified as positive prognostic criteria. Finally, STMM seems to prefer the limbs and the pelvic girdle as its primary location [5]. This case report describes our experience regarding a patient affected by an STMM with in transit and subsequent systemic metastases.

CASE REPORT

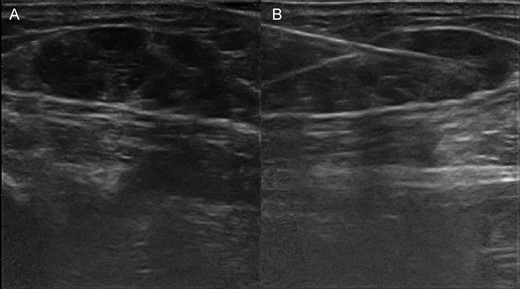

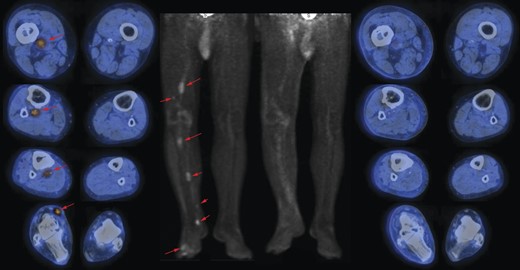

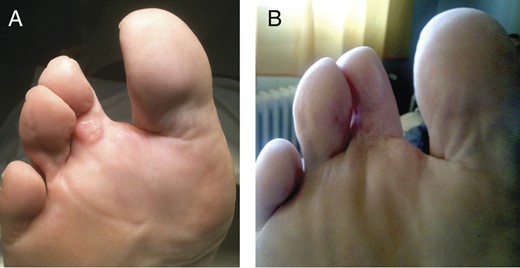

A 61-year-old male patient with no particular previous illnesses was diagnosed with a well-differentiated STMM of the plantar surface of the second toe of the right foot, with infiltrated margins after excisional biopsy. Microscopically, myoepithelioma consists of nests and cords of epithelioid, plasmacytoid or spindle cells, with inconspicuous nucleoli, mainly eosinophilic cytoplasm and, in some cases, clear cells. The cells are embedded in a chondromyxoid, collagenous or hyalinized stroma; no significant nuclear pleomorphism is usually observed and mitoses are scarce. The malignant variant is exclusively recognized by its histological features, showing a marked cytologic atypia, prominent nucleoli, necrosis and a high mitotic index (>7/10 HPF) [2, 5]. The patient underwent computerized tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen for staging; the results were normal. Considering the residual disease in the previous excision of the nodule, the patient underwent a radical disarticulation of the toe 20 days after excisional biopsy. Three months later, the patient presented a lump on the plantar surface of the third toe of his right foot, a subcutaneous nodule on the right ankle and another nodule on the back of the foot; excisional biopsy of the latter showed de-differentiated STMM. Because of these findings, a positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) [7] was performed, which showed the presence of in-transit metastases in the right lower limb, extending to the middle third of the thigh. Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was performed at the level of the most accessible of these lesions, which confirmed secondary STMM (Fig. 1). The patient was then treated with hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion (HILP) using human recombinant tumor necrosis factor 1 mg and melphalan 90 mg. During the subsequent follow-up, a complete response was documented (Figs. 2 and 3).

(A) Ultrasonography shows in-transit metastases by malignant myoepithelioma in the soft tissue of the leg. (B) Performing fine-needle aspiration under ultrasonography guide of the in-transit metastases of the leg.

On the left side: images (transaxials fused and maximum intensity projection) of pre-HILP 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET/CT showing areas (red arrows) of increased uptake representing in-transit metastases in the right lower limb, extending to the thigh; on the right side: images (transaxials fused images and maximum intensity projection) of post-HILP showing clear reduction of pathological uptake of 18F-FDG.

(A) Local recurrence of STMM on the third toe. (B) Disappearance of local recurrence of STMM on the third toe (post-HILP).

Fourteen months after the removal of the primary tumor, a pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (RMI) identified the presence of lymph nodes highly suspicious for malignancy in the right groin region. FNAC confirmed the presence of metastases from STMM and a complete surgical dissection of the inguinal-iliac-obturator lymph nodes was performed. The histological report documented the presence of metastases from differentiated STMM at the inguinal and iliac lymph nodes. During the following months, the patient was followed up clinically and radiologically, and all examinations were negative.

Twenty-two months after the removal of the primary tumor, pathologic non-lymphatic nodules at the inguinal and iliac areas were noticed and initially treated with cisplatin plus doxorubicin, but concomitant pelvic progression was ascertained. Afterwards, three cycles of ifosfamid in continuous infusion (14 g/mq in 14 days every 28 days) and radiotherapy (50.4 gray in 28 fractions to the inguinal-iliac-obturator region and one boost of 64.8 gray into the area where the recurrences were found) were administrated with complete response. Currently, 36 months from the original diagnosis, the patient is alive and in good health, and undergoes follow-up examinations every 4 months.

DISCUSSION

STMM is a rare disease, and diagnosis, staging and treatment of STMM are not yet standardized. Therefore, each single case of STMM should be discussed by a multidisciplinary team and treated in highly specialized sarcoma centres. Given the aggressiveness of the disease, which frequently evolves into distant metastases (41%) [5], CT of the chest and abdomen or PET-CT is useful in the initial staging and follow-up inspections every 4 months. In the literature, no case of in-transit metastasis from STMM has been reported. Thus, taking into consideration our case with deep in-transit metastases of the lower limb, we believe that PET-CT should be considered for staging instead of CT scan. From data analysis in the literature, STMM metastasizes to lymph nodes in 11.8% of cases; therefore, no indication is given for sentinel lymph node biopsy. It is important to proceed to a radical wide surgical excision, as the early local recurrence rate reported in the literature is ∼30% [5]. Regarding the use of HILP as a curative procedure, no experience has so far been reported in the literature for STMM with in-transit metastases. In our case a complete tumor response obtained in this case after HILP made it possible to avoid limb disarticulation. In the literature three cases of STMM unresectable and solitary (without metastases in transit) are reported, who underwent HILP without response, and led to amputation of the limb [6, 8]. Despite this, HILP may be proposed in the neo-adjuvant setting for STMM with in-transit metastases based on the results obtained in our patient.

STMM is generally described as poorly responsive to systemic chemotherapy [1, 6]; however, we observed a complete response with ifosfamid and melphalan. The role of RT alone, as a solitary treatment, seems to be marginal and with little evidence of effectiveness. It may have a role in the adjuvant setting after marginal removal of the primary tumor. In our experience, it was also effective in combination with chemotherapy for the local control of unresectable metastases. Finally, it is interesting to note that, from a histological point of view, the tumor of our patient underwent multiple differentiations (primitive tumor: differentiated; metastases in-transit: de-differentiated; finally ileo-inguinal lymph node: re-differentiated). These different phases may explain the positive response to HILP and chemotherapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dott.ssa Christina Drace for her translation advice. The authors permit to reproduce copyright material, for print and online publication in perpetuity. The authors confirm written patient consent is available for the case report.