-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Malcolm C. Aldridge, Camilla Nederstrom, Rajiv Swamy, Splenic marginal cell lymphoma (SMZL): report of its presentation with spontaneous rupture of the spleen, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2013, Issue 12, December 2013, rjt105, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjt105

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Rupture of the spleen is a potentially life-threatening condition, which most often occurs secondary to abdominal trauma. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen is a much rarer event, usually occurring secondary to infections and less frequently secondary to haematological malignancies causing massive splenomegaly. We present a case of a 71-year-old woman who presented in the emergency department with acute abdominal and back pain and no history of trauma, with a CT scan diagnosis of splenic rupture. Splenectomy was performed and the histological examination of the specimen revealed splenic marginal cell lymphoma (SMZL), which is classified under the non-Hodgkins lymphomas (NHL) and accounts for <1% of NHL. There is only one previously reported case of spontaneous splenic rupture SMZL and this is the first recorded case of spontaneous splenic rupture in a patient without massive splenomegaly.

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous splenic rupture occurs usually secondary to abdominal trauma, most often in a spleen affected by infection or haematological malignancy [1]. Spontaneous splenic rupture is extremely rare, especially presenting in a patient subsequently diagnosed with splenic marginal cell lymphoma (SMZL), which itself is rare and as a result only one case has been described in the literature so far.

CASE REPORT

We report a case of a 71-year-old woman with a past medical history of inflammatory myelitis, osteoporosis, asthma, coeliac disease and chronic back pain who was admitted as an emergency with new onset and severe back and abdominal pain. She described a 5-day history of persistent bilateral back pain radiating to the shoulder tips and groin worse when lying flat. There was no reported history of trauma or falls.

The patient was haemodynamically stable with a slightly distended soft but generally tender abdomen. On admission the haemoglobin was 61 g/l and haematocrit 0.189 l/l. She attended the emergency department 3 days before with a similar complaint but discharged home the same day. The haemoglobin was noted to be 117 g/l during that admission. The inflammatory markers were following: CRP 88 and white cell count 12.3; biochemistry and clotting screen was normal.

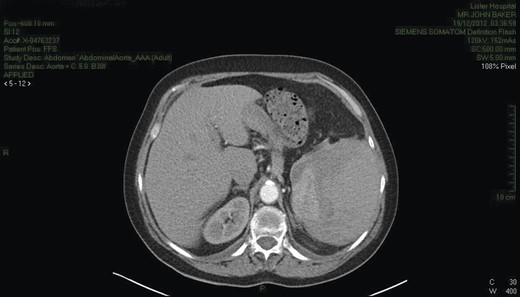

CT scan (Fig. 1) was consistent with splenic rupture. Laparotomy was performed and a large splenic haematoma with ∼1 l of blood in the abdomen and a splenectomy was performed. The postoperative period was complicated by a lower respiratory tract infection and some difficulty with mobilization but the patient made good recovery otherwise. During the post-operative period she developed a hypoglossal nerve palsy, which was assessed by the neurologist. An MRI scan failed to reveal a cause and the palsy settled spontaneously. She was discharged after 21 days.

CT chest/abdomen demonstrating a large splenic haematoma with hyper- and hypo-dense areas. High attenuation fluid is present within the pelvis consistent with blood.

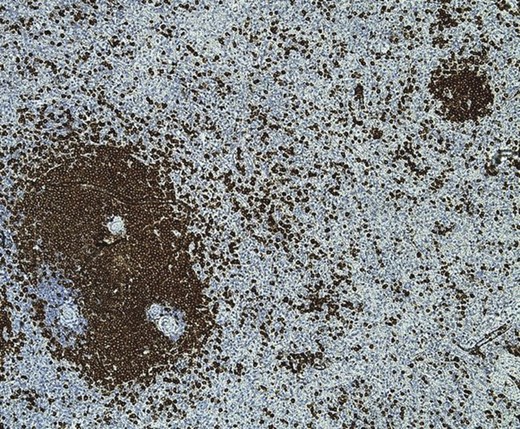

The excised spleen weighed 560 g with blood clots and was macroscopically normal. Microscopically (Figs 2–4), the histology and immunohistochemistry was consistent with a diagnosis of SMZL. Subsequently, a bone marrow biopsy and staging CT were performed and no distant spread of disease was demonstrated. The patient is undergoing regular follow-up in the haematology clinic.

CD79a immunohistochemistry ×20. CD79a highlights the presence of marginal expansion of the white pulp lymphoid mantle with satellitosis (nodular infiltrates) in the red pulp. The monomorphic population of medium-sized lymphoid cells also stained positive for CD20, Bcl2, IgM and IgG consistent with SMZL.

Marginal expansion of the white pulp lymphoid mantle with satellitosis in the red pulp.

DISCUSSION

The term spontaneous rupture is poorly defined in the literature and distinguished from pathological rupture of the spleen. Dating back to 1958 Peskin and Orloff described true spontaneous rupture in cases where there is no trauma pre- or intraoperativly, the spleen is not affected by any disease, no perisplenic adhesions present indicating previous splenic trauma and on gross and histological examination of the spleen must be normal. However, in the current literature, spontaneous splenic rupture describes a splenic rupture occurring without trauma whether the spleen is involved in pathology or not [3]. Three main mechanisms can explain splenic rupture. First, in haematological malignancies, the splenic parenchyma gets congested with blast cells causing increased intrasplenic tension, which exceeds the capacity of the non-distensible splenic capsule and eventually results in rupture. Secondly, vascular occlusion secondary to reticular endothelial hyperplasia results in thrombosis and infarction, which may distort the splenic architecture making it weaker and thirdly deranged coagulation, which may be part of a systemic disease or caused by thrombocytopenia secondary to massive splenomegaly [4].

Splenic rupture is a life-threatening event and a differential diagnosis in a patient presenting with acute abdomen, although not all cases present with abdominal pain. Haemodynamic instability and Kehr's sign, defined as left hypochondriac pain radiating to the left shoulder, occurs in 20% of cases although neither signs are sensitive nor specific. Ultrasound scanning, which is usually readily available in emergency departments, is often a choice of initial imaging and is 72–78% sensitive and 91–100% specific [2].

Treatment of splenic rupture depends on the site and size of rupture, whether the patient is haemodynamically stable and the underlying pathology causing the rupture. In haemodynamically stable patients it is becoming more common to treat patients by splenic artery embolization, whilst unstable patients require surgical management [5, 6].

Splenic marginal zone lymphoma is classified under the non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHL) and account for <1% of these. Marginal cell lymphomas are indolent small B-cell lymphomas, which originate from the marginal zone of the lymphoid follicle, which consists of a germinal centre surrounded by a corona that is divided into the marginal zone and the mantle zone. The World Health Organization classifies the marginal zone-derived lymphomas into splenic (SMZL), lymph node (nodal marginal zone lymphoma) and extra-nodal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) despite having a common origin in the marginal zone of the B-follicle as they have distinct clinical and molecular characteristics [2, 7].

SMZL usually presents as massive splenomegaly and/or with abnormalities in the full blood count, especially anaemia and thrombocytopaenia usually secondary to splenic sequestration rather than bone marrow infiltration [5, 7]. Retrospective analysis of blood results dating back a number of years, revealed no abnormalities in the full blood count; therefore, it appears that splenic rupture was the first presentation in this case and she is in remission at present after undergoing splenectomy as no distant disease was found.

The treatment of SMZL is not standardized and there are no reported prospective studies comparing outcome with immunotherapy, chemotherapy or splenectomy. In the past splenectomy was regarded as a choice of treatment until rituximab was introduced, which has shown responses of up to 100%. This trial concludes that splenectomy should not be regarded as first-line treatment but considered in patients who do not respond to immunotherapy or chemtotherapy. Patients with splenomegaly may suffer abdominal discomfort, early satiety and cytopaenias where splenectomy is indicated for palliative purposes [7, 8]. As this lady presented with spontaneous splenic rupture, it raises the question that when and if splenectomy should be performed prophylactically if picked up on a scan or whether surveillance is indicated but at present the literature does not address this question but ultimately comes down to assessing each individual case taking into account their overall health and stage of disease.