-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

N Ehsani, J Rose, M Probstfeld, Appendiceal endometriosis presenting as a cecal mass, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2012, Issue 4, April 2012, Page 10, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2012.4.10

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Appendiceal intussusception is described, in the surgical literature, as a rare entity with a 0.01% incidence (1). Presenting symptoms can be vague, and preoperative diagnosis is difficult. Given concerns about malignancy, complete surgical removal of the mass and histologic examination of the specimen are paramount, in order to ensure correct diagnosis and proper treatment. Herein, we describe the case of a 44-year-old woman with appendiceal endometriosis leading to intussusception.

INTRODUCTION

Tumors of the appendix are rare entities that are difficult to diagnose preoperatively. Appendiceal masses can present as acute appendicitis. An appendiceal tumor could be a carcinoid, adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, or cystadenoma (2). Therefore, complete surgical resection of the mass and histologic examination of the specimen is central to correctly diagnosing and properly treating appendiceal intussusception, which was first reported in 1858 by McKidd (3). It remains a rare (0.01% incidence) but well-described entity (1,4). Its presentation includes vague intermittent abdominal pain with gastrointestinal symptoms such as episodic diarrhea (1).

When the appendix is involved in endometriosis (proliferation of endometrial glands outside the uterine cavity), the endometriosis deposits can lead to hyperperistalsis and intussusception of the appendix, wholly or partially (1).

The cause of endometriosis is unclear, but several theories postulate direct intraperitoneal shedding of glands through the fallopian tubes and possible lymphovascular spread (5). The common presentation of endometriosis includes pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and infertility, although it can be asymptomatic in some individuals. Endometriosis affects the pelvic reproductive organs and associated peritoneum, followed less frequently by the bowel and bladder (5).

CASE REPORT

A 44-year-old woman came to our medical center with a diagnosis of biliary dyskinesia from an outside institution. However, her symptoms were not consistent with that diagnosis. She had right lower quadrant pain that was intermittent, with no past medical or surgical history of such pain. She was taking only a calcium supplement and a multivitamin. For the past 6 years, she had experienced vague alternating episodes of constipation and diarrhea, with occasional fevers. But she reported no jaundice, no hematochezia, and no weight loss. Her symptoms were not related to meals. We found that her initial vital signs and the results of her laboratory tests and physical examination were within normal limits. Her prior workup had included normal laboratory test results and a normal abdominal ultrasound study; her prior hepatobiliary iminodiacetic (HIDA) scan had revealed a reduced ejection fraction of 7%.

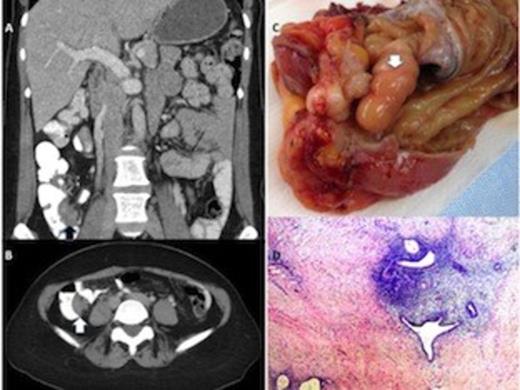

We felt that her symptoms were not consistent with biliary dyskinesia, so we ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan to delineate the cause of her pain (Figure A, B). The CT scan revealed an apparent mass causing a filling defect of the cecum near the appendiceal orifice. A subsequent colonoscopy showed that the appendix was partially intussuscepted, with mucosal thickening at the appendiceal orifice. Because a mucinous cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma was a possibility, we deferred a biopsy.

The patient underwent a laparoscopic ileocecectomy and a cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiography. During the operation, we noted a firm mass at the cecum; in addition, the appendix was partially intussuscepted (Figure C). The specimen was sent for frozen-section analysis, which pointed to a presumptive diagnosis of endometriosis.

The final histopathologic review of the mass was diagnostic of transmural appendiceal endometriosis (Figure D). The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged home. She has since been seen in our clinic and is free of symptoms. She was referred to our gynecology colleagues for management of her endometriosis.

DISCUSSION

In patients with endometriosis, ectopic endometrial tissue typically appears in the pelvis and reproductive organs, but can appear on the bowel and appendix (6). Appendiceal endometriosis is rare (accounting for only 3% of intestinal endometriosis cases) (6), but it can mimic appendicitis, perforation, intussusception, or lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (7). Frequently, such symptoms occur at the time of menses (8). But our patient had intermittent subacute abdominal pain that did not coincide with her menses.

Our gross inspection of the appendix and cecum did not reveal evidence of endometriosis, but rather a firm white mass suggestive of a malignancy. In patients with appendiceal endometriosis, such a lack of a clear pathologic finding is not uncommon; often, the subsequent histologic examination reveals the true diagnosis, with endometrial stroma and glands present in the surgical specimen (9).

In our patient, the appendiceal intussusception found on the CT scan appeared as a cecal mass, more consistent with her symptoms than biliary dyskinesia. It is important to remember that endometriosis can be one of the many causes of an appendiceal mass or a cecal mass, especially in pre-menopausal women. Appropriate treatment includes resection—both to establish a definitive diagnosis and to alleviate symptoms (10). Given the nature of endometriosis, patients like ours should be encouraged to follow up with a gynecologist and should be offered hormonal medical therapy as an adjunct for symptom control.