-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shahana Gupta, Sanjeev Kumar, Ayusman Satapathy, Udipta Ray, Souvik Chatterjee, Tamal Kanti Choudhury, Ascaris lumbricoides: an unusual aetiology of gastric perforation, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2012, Issue 11, November 2012, rjs008, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjs008

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gastrointestinal (GI) infestation with Ascaris lumbricoides is common in the tropical countries, particularly in children. A wide range of clinical presentations are reported for GI ascariasis in both adults and children. We report a case of gastric perforation due to Ascaris, a rare presentation.

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal (GI) tract infestation with Ascaris lumbricoides is a worldwide phenomenon with up to 25% of the world's population, mostly in the third world countries, infested with the worm [1]. While most infested patients are asymptomatic, a wide range of manifestations like bowel obstruction, appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis and perforations have been reported [1]. We report a case of prepyloric gastric perforation due to Ascaris.

CASE REPORT

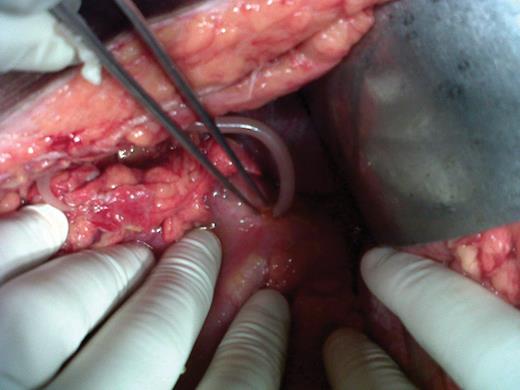

A 48-year-old male patient presented to the emergency room with severe upper abdominal pain along with vomiting for 2 days. There was no history of any drug intake, alcoholism or dyspepsia. He gave a history of occasional passage of round worms with stool. On examination, the patient was febrile with a pulse rate of 130/min and a blood pressure of 110/70 mm Hg. He was severely dehydrated with a low urine output. An abdominal examination revealed evidence of peritonitis. A straight X-ray abdomen showed free gas under both domes of diaphragm. His white blood cell count was 11000/µl, serum urea was 24.1 mmol/l, creatinine was 0.141 mmol/l, sodium was 120 mmol/l and potassium level was 3.1 mmol/l. After adequate resuscitation, an exploratory laparotomy was carried out. On opening the abdomen, air came out and around 1.2 l of bilious fluid was drained. A 1 cm × 1 cm perforation was found in the prepyloric region of stomach and two live Ascaris were seen protruding through the perforation (Figs 1 and 2). There was no scarring or induration around the perforation to suggest a long-standing peptic ulcer disease. A bundle of worms could be palpated within the small bowel. A biopsy from the margin of the perforation was taken. A rapid urease test of the biopsy specimen was negative. The perforation was repaired with Graham's omental patch after extracting the worm protruding through the perforation. Thorough peritoneal lavage was done and the abdomen was closed after placing a drain in the pelvis. The postoperative period was uneventful apart from wound infection which was treated conservatively. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 8 on anthelmentics. A histopathology report of the biopsy from the margin of perforation showed evidence of a focal acute inflammatory reaction. An upper GI endoscopy performed 1 month later did not show any evidence of peptic ulcer disease. These findings helped us in ruling out peptic ulcer disease as an aetiology for the prepyloric ulcer.

DISCUSSION

Ascariasis is a helminthic infestation of global distribution with >1.4 billion persons infested throughout the world. An estimated 1.2–2 million such cases with 20 000 deaths occur in endemic areas per year [2]. The highest prevalence of ascariasis occurs in tropical countries where warm and wet climates provide environmental conditions that favour year-round transmission of the disease. More often, recurrent infestations lead to malnutrition and growth retardation in children in endemic areas. Surgical complications due to Ascaris are rarer in adults [3]. Ascaris is acquired by the ingestion of the embryonated eggs contaminating raw vegetables and fruits. Adult worms inhabit the lumen of the small intestine, usually the jejunum or ileum. Intestinal ascariasis is usually detected as an incidental finding. This can result in a wide range of clinical presentations ranging from asymptomatic worm infestation to intestinal obstruction, perforation, especially ileal, and bleeding [2].

The intestine has an immense capacity for dilatation and can possibly accommodate >5000 worms without any symptoms [4]. The commonest complication of ascariasis is intestinal obstruction due to a worm bolus [5], especially in children with heavy worm load. The obstruction may be acute or subacute. The mechanism of obstruction is occlusion of the intestinal lumen by worms packed in distal ileum as well as localized volvulus of a segment of terminal ileum owing to the weight of the worms inside. Gangrene or perforation may occur as a result of pressure necrosis by roundworms or due to localized volvulus. In intestinal ascariasis, the cause of perforation of the small intestine remains controversial. In the tropics, patients often have associated diseases such as typhoid enteritis, tuberculosis and amebiasis which are known to cause intestinal ulcerations. Intestinal ulcers can also develop due to Crohn's disease, trauma, lymphoma or non-specific ulceration induced by drugs like non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The worm may escape into the peritoneal cavity through perforations at these sites of ulceration [6]. Another possible explanation is that the large worm bolus can lead to pressure necrosis and gangrene [7]. The bowel thus becomes susceptible to perforation by the burrowing action of the worm [2].

Intussusceptions due to Ascaris have also been reported [8, 9]. Acute appendicitis and appendicular perforation can occur as a result of worms entering the appendix. Perforation of Meckel's diverticulum has also been reported to be caused by Ascaris. Granulomatous peritonitis in ascariasis is reported to be due to the presence of dead adult worms in the peritoneal cavity or caused by reaction to the eggs [2]. Ascariasis should thus be investigated in patients with non-specific abdominal pain or intestinal perforation especially in tropical countries to avoid such potentially fatal complications.

There are only two reports in the literature on duodenal perforation possibly caused by Ascaris presenting as an acute abdomen [1, 2]. In a report by Louw [4], a bleeding duodenal ulcer with Ascaris adherent to the ulcer site was found on endoscopy. A gastric outlet obstruction due to Ascaris worm bolus has also been reported [10].

An extensive literature search revealed only one report [3] from Nigeria on possible gastric perforation caused by Ascaris. The lack of any evidence of a chronic gastric ulcer possibly supports the view that the perforation was caused by the worm rather than the worm exiting through a pre-existing perforation. The case we report also has similar findings in the form of absence of any evidence of peptic ulcer disease or NSAID use in a patient with prepyloric perforation through which Ascaris was found to protrude.