-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mark George, Tobias Evans, Andreas L. Lambrianides, Accessory spleen in pancreatic tail, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2012, Issue 11, November 2012, rjs004, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjs004

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Intrapancreatic accessory spleens are common asymptomatic masses that generally cause no problems. Usually, they are incidentally found on imaging as a pancreatic mass and they pose a diagnostic and management dilemma due to equivocal imaging findings. Evolving imaging modalities and increasing use of endoscopic ultrasound with fine needle aspirate may result in the avoidance of unnecessary operations and surveillance. We report a case of distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy for a pancreatic tail solid lesion.

INTRODUCTION

Accessory spleens result from the failure in the fifth week of foetal life of groups of mesodermal cells in the dorsal mesogastrum [1]. They are relatively common, with an autopsy study involving 3000 patients identifying 364 accessory spleens, of which 61 were found in the pancreatic tail [2]. Whilst the pancreatic tail and the splenic hilum are the most common sites, accessory spleens can be found in the stomach, jejunum, mesentery as well as the ovaries and testis [2]. Despite being common, they are rarely noted radiologically because the spatial resolution has been too low [3]. Accessory spleens themselves have no clinical consequence unless a patient suffers from a disease like idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura. However, as they are commonly mistaken for tumours, patients undergo needless operations for removing the lesion. Consequently, it is important to accurately differentiate an accessory spleen from other pancreatic lesions requiring more aggressive treatment.

CASE REPORT

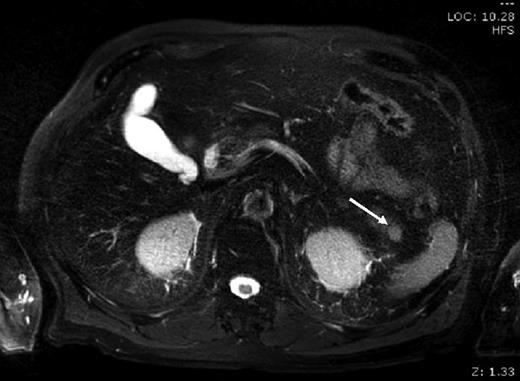

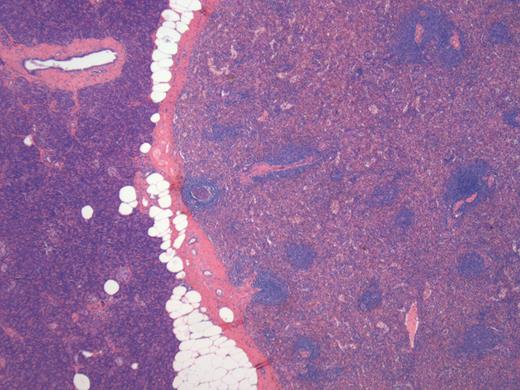

A 76-year-old male presented to his general practitioner with nausea, weight loss and change in bowel habit. A recent colonoscopy was unremarkable, a computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis showed a homogenously enhancing 13-mm lesion in the tail of the pancreas, with the reported differentials including neuroendocrine tumour or a pancreatic adenocarcinoma. A subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) illustrated the lesion enhancing homogenously in the portal venous post-contrast phase suggesting a solid neoplastic lesion, likely to be primary (Fig. 1). He went on to have a distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy with an uneventful recovery. Pathology revealed a splenunculus with no evidence of malignancy (Fig. 2).

MRI: small round lesion in the pancreatic tail measuring 1×1 cm, enhancing homogenously in the portal venous post-contrast phase suggesting a solid neoplastic lesion. The differential includes primary pancreatic lesion such as a small mucinous cystic pancreatic tumour or an islet cell tumour

Histology of the lesion showing the normal pancreas on the left with the accessory spleen on the right

DISCUSSION

Pancreatic cancer was the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in Australia in 2010 [4]. Surgery offers the only chance of cure; however, most patients have unresectable disease at the time of presentation. In potentially resectable disease, the high false-negative biopsy rate of 20% and the potential complications arising from the biopsy generally discourage most surgeons from pre-operative tissue biopsy [5]. Because of this, radiological methods are used to differentiate the bulk of malignant and benign lesions. MRI, CT, ultrasound scan (USS) and scintigraphy are all used for this purpose.

Ultrasound usually shows an accessory spleen as a round, mildly echogenic mass with homogenous texture and posterior enhancement [6]. Importantly, Doppler USS has a sensitivity of 90% when a vascular hilum entering the lesion is identified [6]. Also, inhomogenous enhancement due to the differing flow rates between the red and white pulp of the accessory spleen may indicate splenic tissue. During the other phases, the lesion enhances homogenously.

CT is commonly the modality in which the pancreatic lesion is first identified. Triple-phase CT is usually performed to differentiate pancreatic lesions, and the attenuation of accessory spleens in the pancreas is usually identical to that of the spleen in all three phases. Generally, this means that the splenic tissue will be brighter than the normal surrounding pancreatic tissue. In comparison, most pancreatic tumours (including islet cell tumours) are brighter on the arterial phase, and lower on the venous phase.

MRI has only recently been readily used for differentiating pancreatic lesions. Pancreatic tumours share signal characteristics with that of the spleen [3], which makes differentiation difficult. Despite this, the fact that the signal intensity (SI) of accessory spleens is usually identical to that of the spleen can lead to the diagnosis. In rare instances, the SI is different due to differing amounts of the red and white pulp in the accessory spleen. Another differentiation can be found with the fact that tumours usually contain areas of haemorrhage and necrosis, which is readily demonstrated with MRI. A solid, homogenously enhancing mass would be very unusual for a neoplasm [7].

Scintigraphy using Tc-99m heat-damaged red blood cells (HDRBCs) is a highly specific medium used to detect accessory spleen tissue. The technique uses autologous HDRBCs which are converted into rigid spherocytes, injected and then sequestered in the spleen, as well as any functioning accessory splenic tissue. Despite this, the sensitivity is poorer than other modalities as it requires a certain amount of functioning splenic tissue. Consequently, scintigraphy is ideally suited to confirm the diagnosis of an accessory spleen.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine needle aspirate (FNA) is increasingly used to characterize both solid and cystic lesions in the pancreas and obtain specimens for pathological diagnosis. There is minimal literature on pre-operative diagnosis of intrapancreatic accessory spleens (IPAS) with isolated case reports of confirmation on histology and immunohistochemical staining for CD3 and CD20 [8] to distinguish from adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Adequate sampling with confident pathological reporting may result in the avoidance of distal pancreatectomy and also of prolonged surveillance if a ‘watch and wait’ approach is utilized.

Modern radiological techniques will lead to an increasing number of IPAS identified and this poses a significant diagnostic and treatment challenge. Pre-operative diagnosis based on radiological findings can be difficult and aspiration cytology can be misleading. Identifying the IPAS is very important as it can mimic either primary or secondary lesions of the pancreas which may result in an unnecessary operation with the involved risks entailed. In our case, emerging imaging modalities may have resulted in an operation being avoided with confident radiological/cytological diagnosis. Emerging techniques such as EUS with FNA may provide confident diagnosis of IPAS; however, equivocal pathological findings will continue to lead to unavoidable operations for IPAS.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.