-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

KH Hutson, JC Fleming, JA McGilligan, Just a simple case of tonsillitis? Lemierre’s Syndrome and thrombosis of the external jugular vein., Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2011, Issue 4, April 2011, Page 6, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2011.4.6

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Oropharyngeal infections are routinely encountered within general practice and accident and emergency departments. Most settle with simple analgesia and antibiotics; occasionally such patients may develop Lemierre’s syndrome (LS) a rare and potentially fatal sequela that can be easily overlooked. We aim to highlight the main symptoms, pathology, investigations and management.

INTRODUCTION

LS was first described as a ‘postanginal septicaemia’ in the early 20th century; originally associated with a mortality reaching 90% it involves a classic triad of oropahryngeal sepsis, internal jugular vein (IJV) thrombophlebitis and metastatic abscess formation (1). Clinical findings can therefore vary considerably from neck pain and swelling associated with thrombophlebitis to pleuritic chest pain, haemoptysis, dyspnoea or arthralgia as a result of septic thromboemboli. Meningitis, peritonitis and clinical jaundice have also been described (2). We report a case of predominantly external jugular vein (EJV) involvement in an adolescent male with negative blood culture results.

CASE REPORT

A twelve year old boy presented to the children’s assessment unit with a 24 hour history of unilateral face and neck swelling on a background of seven days progressive sore throat and dysphagia. Minor systemic upset was also noted including headache, vomiting and non specific abdominal pain. A provisional diagnosis of tonsillitis had been made five days earlier by the local GP and a course of erythromycin and penicillinV commenced.

Examination revealed tender swellings over the left temporal area, angle of the mandible and upper third of the sternocleidomastoid extending into the submandibular region. Lymphadenopathy was present and limited to the left submandibular area.

Examination of the oral cavity was complicated by trismus, however no obvious tonsillar enlargement, erythema or exudate was recorded. Further systems examinations were unremarkable, observations were stable and he remained afebrile.

Initial blood results showed an elevated C-reactive protein of 155mg/L and white cell count of 16.6(10*9L). A septic screen was undertaken and blood cultures obtained. A chest x-ray showed clear lung fields with no pulmonary lesions. Initial imaging of the neck comprised an ultrasound scan; this demonstrated normal right sided vasculature but abnormal left EJV and retromandibular veins. These veins appeared dilated with increased wall vascularity and showed no recordable signal on doppler imaging, an appearance in keeping with an inflammatory thrombophlebitis. To note the left IJV remained patent with good demonstrable flow.

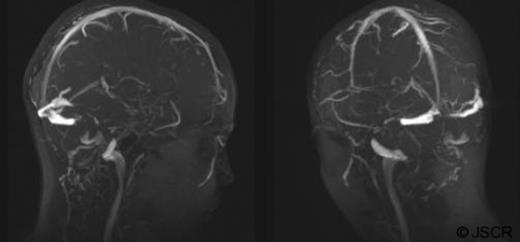

An MRI brain with venography (MRV) sequences provided greater anatomical delineation (figure 1). Despite a coincidental finding of a smaller calibre left venous sinus; thrombus was not seen to extend intracranially. Lastly an echocardiogram was sought confirming a normal heart with no septal defects, vegetations or thrombus.

MRV brain images demonstrate bilateral sagittal, straight, transverse and sigmoid sinuses with no evidence of thrombus extension. Both right and left IJV as well as right EJV are clearly patent. The left EJV could not be demonstrated.

Throat swabs and serial blood cultures failed to successfully isolate any pathogens. Treatment was started promptly on clinical suspicion of LS and consisted of intravenous (IV) metronidazole, benzyl penicillin and dexamethasone; anticoagulation was not given. The patient remained in hospital on IV antibiotics for a total of 14 days, the noted swellings slowly decreased in size, blood results normalized and the trismus resolved. He remained afebrile throughout, developed no subsequent complications and was discharged home to complete seven weeks of oral antibiotics.

DISCUSSION

Despite IJV thrombophlebitis forming a main diagnostic criterion for LS, we report a case in which the primary vascular involvement is that of the EJV, with a corresponding normal IJV. Studies have previously described LS with thrombosis of the carotid artery, intracranial venous sinus and abdominopelvic vessels (1); only three have ever described involvement of the EJV. This unusual finding helps to highlight the variable nature of this condition and the diagnostic confusion it may herald. To note there are reported cases of LS in which there was no demonstrable vascular involvement. Numerous theories have tried to explain the spread of organisms from oropharynx to the surrounding vein; haematogenous via the tonsillar vein, secondary to lymphangitis or via direct spread through deep neck spaces. Non however have been conclusively demonstrated. (3)

The incidence of LS within developed countries is now thought to lie around one per million per year, significantly reduced from the pre antibiotic era, however a resurgence over the last decade has recently been proposed. Mortality has been recorded at 6.9% however morbidity and complications remain high as the early diagnosis can often be missed and treatment delayed. (3)

Although classically described as following an oropharyngeal infection LS has been reported developing from other primary infective sites including the middle ear, sinuses, mastoid and teeth (1). The development of sepsis in LS is often delayed, presenting three to seven days from signs of the primary infection, which may have all but resolved (4), making accurate history taking and a high index of clinical suspicion ever more important.

LS is classically but not exclusively associated with an obligate oropharyngeal gram negative bacillus; fusobacterium necrophorum. Other causative pathogens described in the literature include streptococcus, staphylococci and bacteroides species (5). It has however been reported that in almost 13% of cases no pathogen is isolated on culture (6). Treatment consists of lengthy antibiotic therapy; typically a penicillin plus anaerobe cover. LS can also be associated with thrombophillia (thought to be endotoxin induced) (5). The role of anticoagulation however remains controversial with no conclusive literature evidence; the decision should therefore be made on clinical grounds; assessing severity of symptoms, poor treatment response and degree of thrombus extension.

A recent history of a sore throat in conjunction with sepsis and or a suggestive and often declining clinical picture should always prompt early antibiotic therapy whilst a diagnosis of LS is sought; hopefully preventing the development of late embolic complications. Differential diagnoses to consider include infectious mononucleosis, parapharyngeal abscess, lymphoma, pneumonia (including atypical forms) and other embolic sources (e.g. infective endocarditis).