-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hasib Ahmadzai, Liver abscess or neoplasm? A diagnostic and surgical dilemma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2010, Issue 8, October 2010, Page 5, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/2010.8.5

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma can is often associated with hepatitis B infection. With localised tumours, liver resection can result in a cure. This case presents an unusual finding of concurrent hepatitis B and liver fluke infection with hepatocellular carcinoma in a 50 year old man from Thailand. The discussion illustrates difficulties of arriving at a diagnosis and ensuring appropriate surgical management.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma is known to be strongly associated with hepatitis B infection. This report highlights a rare case of concurrent hepatitis B and liver fluke infection with hepatocellular carcinoma, presenting clinically as a diagnostic and surgical challenge.

CASE REPORT

A 50 year old male from Thailand presented complaining of right upper quadrant abdominal pain, jaundice, 4kg weight loss over 2 months and hepatomegaly. His abdominal pain was sharp and intermittent, exacerbated by deep inspiration, although did not radiate and was not associated with eating. He complained of night sweats and a fever spiking at 40.0°C. He did not experience nausea, diarrhoea and was able to pass brown stool and clear urine. He did not have a significant past medical or surgical history, however, his father had died from cholangiocarcinoma. There was no significant alcohol history. The patient stated he often travelled to north Thailand where he “ate raw fish” but there was no illness reported in contacts.

Physical examination revealed a jaundiced, alert and ambulant patient with no signs of wasting. Cardiorespiratory examination was normal. Abdominal examination revealed tenderness, guarding at right hypochondrium with palpable hepatomegaly and positive Murphy’s sign. There was no abdominal distension or ascites. He was found to be hepatitis B surface antigen positive with moderate to high viral load given by virus DNA levels of 523 277IU/mL. He was positive for hepatitis B core antibody and hepatitis Be antibody, hepatitis Be antigen negative, implying chronic infection. The man had deranged liver function tests including total bilirubin 95μmol/L, ALP 256U/L, ALT 267U/L; AST 289U/L, γ-GT 985U/L but normal albumin (32g/L) and prothrombin time (13.1sec). Full blood count revealed mild anaemia, elevated WCC, neutrophils = 8.9×109/L, eosinophils = 9.1×109/L and CRP = 223mg/L.

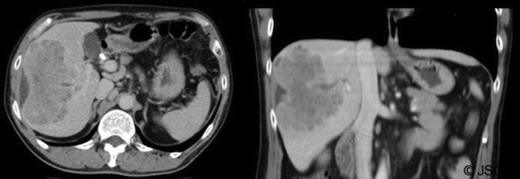

Abdominal ultrasound displayed biliary sludge although no gallstones with normal thin-walled gall-bladder. Abdominal CT-scan with contrast revealed a right liver mass involving segments V to VIII measuring 10.6cm×6cm axially and 10cm craniocaudally with mild caudate lobe hypertrophy suggesting underlying cirrhosis; intra-hepatic bile duct dilation, subcapsular fluid and lymphadenopathy (figure 1).

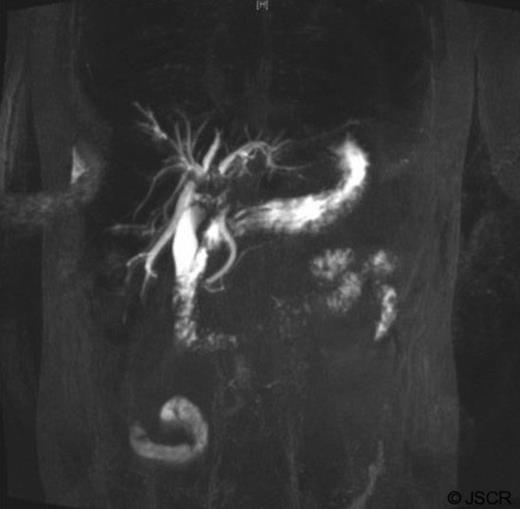

Tumour markers revealed elevated carbohydrate-antigen 19-9 at 807kU/L (normal <40kU/L) suggesting bile-duct disease (1) whilst α-fetoprotein was 4kU/L, within normal range. Magnetic resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) indicated filling defects in right and left bile ducts (figure 2) and portal vein thrombosis.

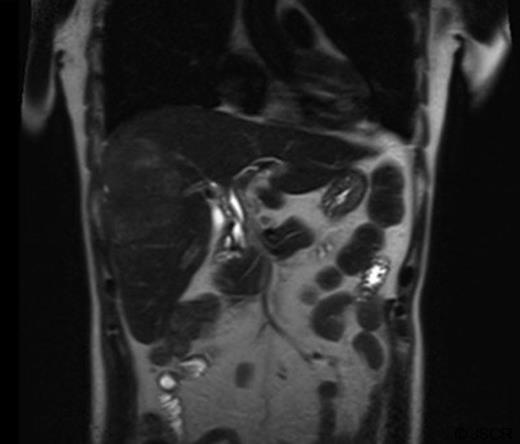

The mass had mild hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images and capsule retraction, suggesting a scirrhous lesion (figure 3); possibly cholangiocarcinoma.

T2 weighted abdominal MRI, coronal view displaying right lobe liver mass.

ERCP showed casts occupying the hepatic ducts and motile liver flukes were identified. A 10-French stent was inserted and sphincterotomy performed to drain sludge. ERCP histopathology specimens revealed necrotic tissue with eosinophils, although no ova/parasites were visualised. Stool samples did not identify ova so blood samples were taken for serology testing including Clonorchiasis andOpisthorchiasis (results pending at time of publication). Total quantitative immunoglobulins revealed elevated IgA (7.05g/L) and total IgE (874 IU/ml), consistent with a parasitic infection and/or neoplasia. The patient was given 3 doses of 75mg/kg praziquantel for parasites; ciprofloxacin and metronidazole for cholangitis and initiated on warfarin for portal vein thrombosis. Three weeks later his symptoms resolved and stent was removed, ERCP indicating drainage and dead flukes. Despite radiological findings suggesting neoplasia, possibility of liver abscess was still likely. A decision was made not to perform liver biopsy, due to potential for peritoneal tumour seeding if the mass was neoplastic and instead he was monitored on an outpatient basis.

Over the next few months, the man was admitted for repeated cholangitis episodes. ERCP now indicated intra-hepatic duct filling defects (figure 4) and sediment was removed with new stents placed. Repeat abdominal-CT scans indicated the mass was similar in size. Following these presentations, the multidisciplinary team decided to undertake laparoscopic liver biopsy.

Core biopsies microscopically showed a tumour with vague trabecular architecture, bands of fibroblastic stroma and focal necrosis. Neoplastic cells were large, granular and glycogen rich. Immunoperoxidase staining was positive for Cam 5.2, Hep Par-1, and CEA, indicating the lesion was most likely hepatocellular carcinoma. Right hemihepatectomy was performed one week later; the patient recovered with no recurrent episodes of cholangitis.

DISCUSSION

The major problem encountered in establishing diagnosis and surgical management in this case was the potential risk of needle-track tumour seeding following percutaneous hepatic biopsy, with a reported likelihood estimated as high as 1% (2). Facilities were not available to perform transjugular hepatic biopsy so it was decided to undertake laparoscopic biopsy. Since the patient had chronic hepatitis B infection, there was also risk that he may have underlying cirrhosis and hence hepatectomy was delayed until biopsy could be obtained to ascertain the nature of the lesion. Biopsy acquisition allowed correct diagnosis and surgical management to be ensued.

This case also presented diagnostic challenges since liver fluke infections can cause liver abscesses, cholangiocarcinoma and recurrent cholangitis (3) whilst hepatocellular carcinoma incidence is ~100 fold higher in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Common human liver flukes include Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrini, Fasciola hepatica and Schistosoma species. Schistosomiasis usually causes other features including urticaria, cough/wheeze, diarrhoea and urinary symptoms. Opisthorchis andClonorchis infection is endemic in South-East Asia, with prevalence up to 80% in some areaa (4) with infection being caused by ingestion of improperly cooked fish, part of the diet in these regions. Cholangiocarcinoma has been linked to C. senesis infection in China and O. viverrini in North Thailand (5,6). It is also known that in Thailand ~70-90% of the population are infected with hepatitis B before age 40, with chronic infection prevalence being 8-15% (7). These findings indicate concurrent hepatitis B and liver fluke infection with both being associated with the patient’s presentation.

This case illustrated both a diagnostic and surgical dilemma, which was solved through imaging and biopsy findings allowing correct surgical management.