-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Romke Rozema, Joke-Afke van der Zee, Jacqueline J C van der Meij, Daniel A Hess, Ewoud H Jutte, Fatal liver failure due to retroperitoneal hemorrhage in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy—a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 2, February 2026, rjag034, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjag034

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Postoperative complications following elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy are rare but can have serious clinical consequences. Major complications include bleeding, bile duct injury, bile leakage, as well as bowel and vascular injuries. This case describes a 68-year-old patient in whom elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy was complicated by bile leakage and fatal retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Computed tomography was performed due to postoperative abdominal pain and revealed both intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal fluid. Diagnostic laparoscopy identified free intraperitoneal bile without active signs of bile leakage. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showed no evidence of bile leakage or choledocholithiasis. Computed tomography was obtained due to acute liver failure and demonstrated increased retroperitoneal fluid causing compression of the pancreatic head, duodenum, inferior vena cava, and porta hepatis. Anatomical variations of the hepatic arterial vasculature were also observed. The patient deceased due to multi-organ failure. Autopsy revealed massive retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

Introduction

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the procedure of choice for the surgical management of symptomatic cholelithiasis. Well-known complications of this surgery include injury to the common bile duct or common hepatic duct, bile leakage, and intra-abdominal hemorrhage. We report a case of fatal retroperitoneal hemorrhage as a rare complication following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This case has been reported in accordance with the SCARE criteria [1].

Case presentation

A 68-year-old man with a history of atrial fibrillation underwent an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. The procedure was performed according to the standard of care. The critical view of safety was achieved, and no perioperative complications were observed. On postoperative Day 1, the patient reported mild abdominal discomfort, while vital parameters showed no signs of shock. On postoperative Day 2, laboratory analysis revealed a hemoglobin level of 13.0 mmol/l, a C-reactive protein level of 324 mg/l, a white blood cell count of 17.6 × 109/l, an increase in serum creatinine from 96 to 165 μmol/l, total/direct bilirubin levels of 103/63 μmol/l, and elevated liver function tests (AST: 87 U/l; ALT: 122 U/l). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) demonstrated both intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal fluid, no signs of intra- or extrahepatic biliary dilatation, and focal hypodensity of the pancreas, potentially related to early pancreatitis. In addition, right-sided peripheral pulmonary emboli were diagnosed, and therapeutic nadroparin was initiated. Based on these findings, bile leakage was considered the most likely diagnosis, either due to leakage from the cystic duct stump or accessory bile ducts, or secondary to increased biliary pressure resulting from choledocholithiasis. Post-surgical hemorrhage was considered less likely given the normal hemoglobin levels.

A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. During the procedure, ~800 ml of bile-like fluid was aspirated. The Calot’s triangle was clearly visualized, with three clips in situ and no active signs of bile leakage. A surgical drain was placed in the region of interest. Postoperatively, the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed no choledocholithiasis. Subsequently, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed because of the high suspicion of bile leakage and the absence of another explanatory diagnosis. No choledocholithiasis or bile leakage was observed on cholangiography. An endoprosthesis was placed in the hepatopancreatic ampulla. Based on the cumulative findings, the most likely etiology was a passed choledocholithiasis resulting in transient bile duct leakage and focal pancreatitis.

Unfortunately, during the ICU stay, the patient developed progressive shock, requiring mechanical ventilation and vasopressor therapy. Continuous veno-venous hemofiltration was initiated because of acute kidney failure. Repeat laboratory tests showed a hemoglobin level of 6.7 mmol/l, a C-reactive protein level of 213 mg/l, a white blood cell count of 24.9 × 109/l, and evidence of acute liver failure (total bilirubin 135 μmol/l, AST: 5720 U/l; ALT: 1620 U/l, prothrombin time: 1.9). Multiphase liver protocol CT demonstrated increasing retroperitoneal oedema with complete encasement of both arterial and portal vasculature, resulting in markedly reduced arterial liver perfusion (Fig. 1). An anatomical variant of the hepatic vasculature was noted, with the right hepatic artery arising from a small accessory branch of the coeliac trunk, and the left hepatic artery partially originating from the left gastric artery and partially from the gastroduodenal artery.

Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrating hemorrhage within the hepatoduodenal ligament and decreased arterial liver perfusion.

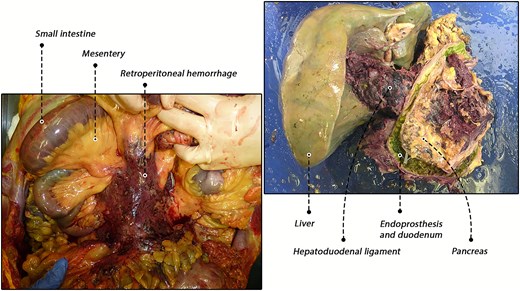

On postoperative Day 8, the patient developed multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and deceased. Autopsy revealed extensive retroperitoneal hemorrhage, most pronounced around the coeliac trunk and superior mesenteric artery (Fig. 2). The aberrant hepatic artery anatomy was confirmed, with a notably small lumen diameter of both arteries. In addition, subtotal hepatic necrosis with thrombosis of the portal and hepatic veins was observed. No other explanatory pathology was found.

Autopsy findings. Left: in situ view of the retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Right: ex situ hepatopancreatobiliary specimen demonstrating hemorrhage within the hepatoduodenal ligament.

Discussion

Although uncommon in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy, complications can have significant clinical consequences. Major complications have been reported in ~1.2% of cases [2]. Hemorrhagic complications range from minor hematomas to life-threatening injuries, such as damage to major abdominal vessels. Depending on the definition applied, these complications have been reported in up to 10% of cases [3]. In most instances, hemorrhage was related to the peritoneal cavity or abdominal wall. Retroperitoneal hemorrhage has been mentioned as a potential complication but has not been extensively described previously [4]. In one study, eight patients were reported with large retroperitoneal vascular injuries during various types of laparoscopic surgery that were not related to trocar or Veress needle insertion [5]. In most of these cases, the inferior vena cava or iliac arteries were affected in patients with distorted abdominal anatomy due to adhesions. Another study reported eight patients with retroperitoneal vascular injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and appendectomy [6]. However, in these cases the injuries resulted from trocar or Veress needle placement.

In the present report, we describe a rare case of fatal liver failure due to retroperitoneal hemorrhage in a patient undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. To our knowledge, such a complication has not been previously reported. The clinical course was extensively discussed internally, and two significant postoperative events warrant further consideration. First, the suspicion of bile leakage in the early postoperative phase. The incidence of bile leakage after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is estimated at 0.3%–2.7% [7]. The most common sources include leakage from the cystic duct stump or accessory ducts in the gallbladder fossa, such as the ducts of Luschka. Although bile leakage was suspected, no definitive cause was identified and the condition was therefore considered self-limiting, potentially originating from a duct of Luschka. The second critical event was retroperitoneal hemorrhage followed by liver failure. An important finding was the anatomical variation of the left and right hepatic arteries. At autopsy, these arteries were shown to have a notably small diameter, making them potentially more susceptible to mechanical traction during laparoscopy or postoperative retroperitoneal changes such as pancreatitis. In addition, the administration of therapeutic-dose nadroparin for pulmonary emboli increased the patient’s risk of bleeding. Our team hypothesized that the retroperitoneal hemorrhage caused compression of the hepatoduodenal ligament and the fragile hepatic arteries, ultimately resulting in ischemic liver failure.

In conclusion, this case demonstrates a rare instance of fatal liver failure due to retroperitoneal hemorrhage in a patient undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anatomical variation of the hepatic arteries was considered a key factor contributing to liver failure. In most patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis, preoperative imaging of the hepatic vasculature is not routinely performed. In these situations, the critical view of safety is applied to avoid biliary and arterial complications. Nevertheless, retroperitoneal hemorrhage should be considered in cases of unexplained postoperative shock.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

None declared.