-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Makaela A Bowman, William A Ziaziaris, David M Joseph, Carlo Pulitano, Michael D Crawford, Jerome M Laurence, Intra-operative detection of cholecystohepatic duct during cholecystectomy: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 1, January 2026, rjaf1116, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf1116

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Biliary anatomy is highly variable, and aberrant anatomy increases the risk of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. Awareness of anatomical variation is essential to prevent avoidable complications. A 37-year-old male with acute gallstone pancreatitis underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anatomy on intra-operative cholangiography was unclear, prompting conversion to open, where repeat cholangiogram showed the common hepatic duct draining into the gallbladder infundibulum. A subtotal cholecystectomy preserving the infundibulum was performed. The patient developed a bile leak requiring re-look laparotomy and hepaticojejunostomy on post-operative day 5, later revised after anastomotic breakdown. He recovered fully and was well at 1-month follow-up. Cholecystohepatic duct is a rare biliary anomaly that is difficult to detect pre-operatively. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography may help, but is not routine, so a high index of suspicion is crucial. Intra-operative cholangiography and a critical view of safety help to prevent injury. Surgical management depends on anatomy, but generally hepaticojejunostomy is recommended.

Introduction

Anatomy of the biliary system is highly variable with conventional biliary anatomy present in only 58%–62.6% of individuals [1, 2]. Anatomical heterogeneity increases the risk of bile duct injury (BDI) during cholecystectomy [3]. Right-sided biliary ductal anomalies are more common and are vulnerable to injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy [2, 4]. We present a case of the rare anomaly of a cholecystohepatic duct that was identified intra-operatively and highlight the diagnostic challenges and operative considerations in its management.

Case report

A 37-year-old male presented with a 2-day history of severe epigastric pain, nausea and anorexia. He had no known cholelithiasis history and consumed five standard drinks per week. Examination demonstrated epigastric and right upper quadrant tenderness with normal haemodynamics. Laboratory work-up showed a lipase of 77 U/L, but was otherwise unremarkable, with normal inflammatory markers and liver function tests. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed acute interstitial pancreatitis of the body and tail with no evidence of complications, while abdominal ultrasound demonstrated small gallstones and biliary sludge. The patient was diagnosed with acute gallstone pancreatitis and commenced on best supportive care with a view to index admission laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

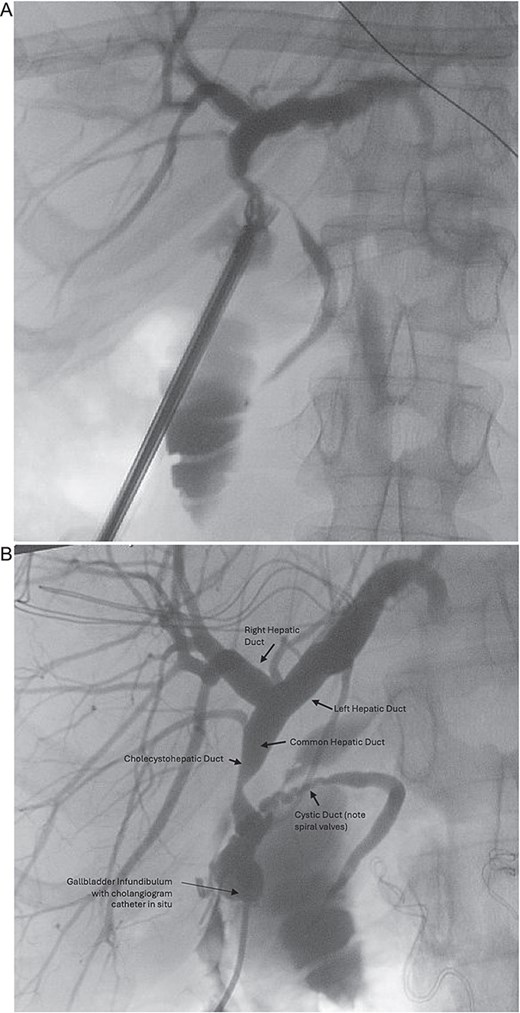

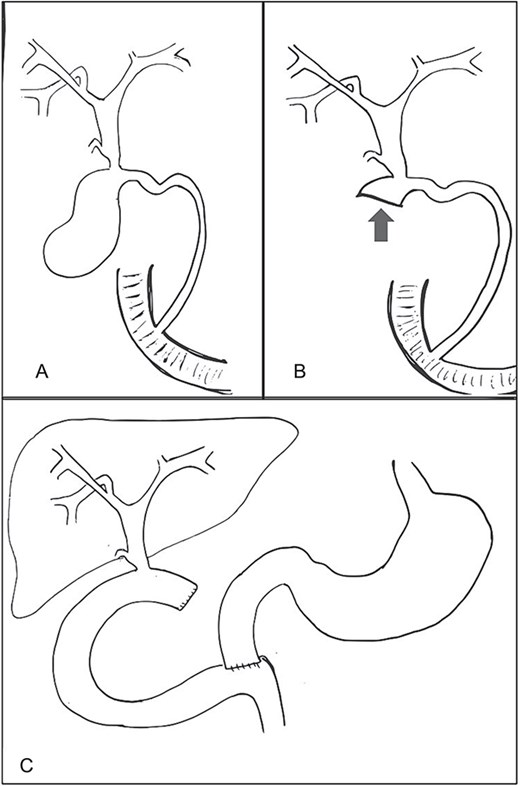

A four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed on Day 3 after symptom resolution. After obtaining the critical view of safety, an incision of the infundibulo-cystic junction was made and intra-operative cholangiogram performed, however biliary anatomy was difficult to interpret (Fig. 1A). The cystic ductotomy was closed and a higher incision on the gallbladder infundibulum made to better delineate the anatomy with a high cholangiogram. Again, biliary anatomy could not be easily interpreted, prompting conversion to open. A third cholangiogram with the gallbladder compressed to facilitate preferential filling of the cystic duct (CD) and common hepatic duct (CHD) was performed, revealing the CHD was draining directly into the gallbladder infundibulum from the liver and that the entire biliary drainage from the liver and gallbladder to ampulla of Vater was via the cystic duct, identified via its spiral valves (Fig. 1B). There was a stricture just proximal to where the CHD drained into the infundibulum, but otherwise the biliary tree was intact with nil evidence of redundancy or stricturing of the CBD (Fig. 2A). There were no large stones, inflammatory erosion, or evidence of cholecystobiliary fistulization to suggest Mirizzi syndrome. After intra-operative consultation with two other consultant hepatobiliary surgeons, a reconstituting subtotal cholecystectomy was performed, ensuring the infundibulum, with the draining CHD and cystic ducts, was preserved (Fig. 2B).

(A) Initial intra-operative cholangiogram, difficult to interpret biliary anatomy. (B) Intra-operative cholangiogram once converted to open, revealed the common hepatic duct was draining directly into the gallbladder infundibulum from the liver, and that the entire biliary drainage from the gallbladder to the ampulla of Vater was via the cystic duct.

(A) Cholecystohepatic duct draining into infundibulum of gallbladder and then via cystic duct to ampulla of Vater. (B) Biliary anatomy following reconstituting subtotal cholecystectomy preserving infundibulum (arrow). (C) Anatomy of bile ducts and drainage following hepaticojejunostomy reconstruction.

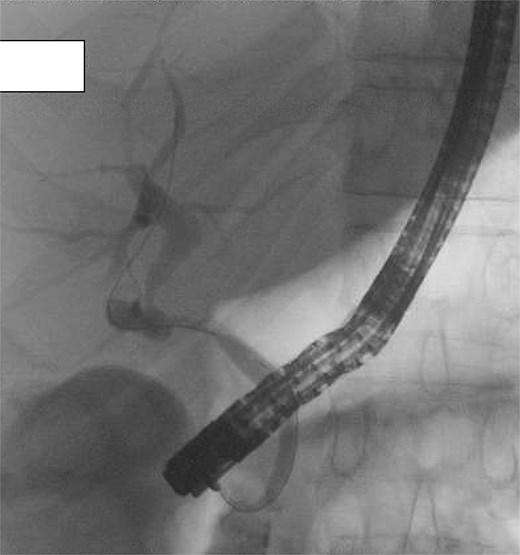

On post-operative day 5, the patient developed abdominal pain and CT cholangiogram suggested possible bile leak. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) demonstrated the flow of contrast into an elongated infundibular-cystic duct channel with no obvious bile leak, filling defects or CBD stricturing (Fig. 3). A sphincterotomy was performed and a 7Fr pigtail stent placed. Symptoms worsened and repeat CT cholangiogram demonstrated large volume intra-abdominal free fluid. On return to theatre, a pinhole perforation in the gallbladder remnant was identified as the source of bile leak, necessitating hepaticojejunostomy. A re-look laparotomy was performed 2 days later, after output >1 L of frank bile in the drain, where a revision hepaticojejunostomy with more proximal duct excision was performed using the Hepp-Couinaud technique [5] to manage anastomotic breakdown (Fig. 2C). The patient recovered well and was discharged. They remained well at 1 month follow-up. Histopathology demonstrated cholecystitis and cholelithiasis with no evidence of malignancy.

Post-operative ERCP demonstrating no filling defects, large stones, or extrinsic compression. Contrast drains from the liver into common hepatic duct and then via an elongated infundibular–cystic duct channel to the duodenum, supporting the diagnosis of a cholecystohepatic duct.

Discussion

This case demonstrates intra-operative identification of a cholecystohepatic duct and its surgical implications. Though, the initial cholangiogram showed a narrowed segment with proximal filling, raising the possibility of a CHD stricture or Mirizzi syndrome, subsequent operative, and endoscopic findings confirmed a cholecystohepatic duct. A cholecystohepatic duct is a rare biliary anomaly where an aberrant hepatic duct drains directly from the liver parenchyma into the gallbladder [6, 7]. While the pathogenesis is not well understood, it is hypothesized to arise from persistent foetal communication between hepatic ducts and the gallbladder with failed recanalization of the CHD [2, 8]. First described by Neuhof et al. in 1945, the combined incidence of all cystohepatic and cholecystohepatic ducts is between 0.2% and 2% [2, 3, 8]. In our case, the entire biliary drainage of the liver was via the gallbladder infundibulum, which is one of the rarest anatomic variations accounted for in this group [7].

Aberrant anatomy is usually detected intra-operatively, often via cholangiography [2, 9]. When aberrancy is suspected, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is the most useful modality for identifying biliary anomalies [2, 4] but pre-operative cholangiography alone does not always delineate biliary anatomy and aberrancy [9]. Awareness of anatomical variation, and maintaining a high index of suspicion is essential for safe cholecystectomy. Although relatively infrequent, with highest quoted incidence ~1% [10], BDI is one of the primary complications of cholecystectomy [4]. Variant biliary anatomy increases this risk because of the vulnerable position of aberrant ducts during dissection [8, 9]. This is further increased if aberrancy is unrecognized pre- or intra-operatively, in cases of surgeon inexperience or as a sequelae of inflammation [3, 4]. Understanding normal and variant biliary anatomy —even extremes such as cholecystohepatic ducts—is therefore important to help prevent iatrogenic injury [4].

Furthermore, we advocate for strict adherence to standard biliary surgical technique and liberal use of intra-operative cholangiography to minimize complications. Meticulous dissection of the hepatocystic triangle and obtaining a critical view of safety allow identification of low hepatic duct insertion and avoidance of BDI [3, 11].

Intra-operative cholangiography is invaluable in delineating both normal and aberrant anatomy, as in this case where it revealed the cholecystohepatic duct as the sole biliary drainage route.

Once identified, surgical management depends on the extent of liver parenchyma drained by the duct and the duct’s entry site into the gallbladder [1]. Conventional management involves ligation of the duct as distal as possible with hepaticojejunostomy reconstruction [3, 7, 8]. In this case, we initially performed a subtotal cholecystectomy as the cholecystohepatic duct connected to the gallbladder and it was deemed possible to preserve the gallbladder infundibulum and leave the CHD and CD intact. This unfortunately broke down secondary to ongoing gallbladder inflammation and, as in most cases, cholecystectomy and biliary reconstruction with a hepaticojejunostomy was necessary [1, 3, 8].

Anatomical variation occurs with sufficient frequency to warrant vigilance among all surgeons performing cholecystectomy. Though rare, our case of a cholecystohepatic duct underscores the importance of understanding biliary variations, using the critical view of safety, routine intra-operative cholangiography and a low threshold to convert to open cholecystectomy should anatomy need further delineation. Here, biliary drainage occurred entirely through the gallbladder, and a subtotal cholecystectomy was attempted but bilioenteric anastomosis is generally recommended.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

None declared.

References

- biliary leak

- cholecystectomy

- cholangiography

- follow-up

- common hepatic duct

- laparotomy

- safety

- surgical procedures, operative

- gallbladder

- laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

- bile duct injuries

- injury prevention

- cholangiogram, intraoperative

- hepaticojejunostomy

- bile leak

- gallstone acute pancreatitis

- infundibular stem