-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Inez Ohashi Torres, Jesus Sebastian Luna Medrano, Samuel Pugliero, Gisela Serra Rodrigues Costa, Erasmo Simão da Silva, Nelson De Luccia, Young patient with aortoduodenal fistula post-tumour resection and aortic graft reconstruction in childhood: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2026, Issue 1, January 2026, rjaf1091, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf1091

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Aortic graft infection is a rare but threatening condition. Early recognition is important but might be challenging. A 25-year-old woman presented with Osler nodes, malaise, fever and multifocal osteomyelitis. Her medical history included a ganglioneuroma resection during her childhood, with aortic reconstruction. A positron emission tomography-computed tomography scan revealed an aortic graft infection. After 2 years of conservative treatment, the patient developed an aorto-enteric fistula, undergoing surgical intervention: graft removal and axillary-femoral bypass. At 20 months follow-up, she remains free of bacteremia. Therefore, graft infection should be considered even many years post aortic reconstruction. Individualized treatment can promote favourable outcomes.

Introduction

Aortic vascular grafts are increasingly used to treat life-threatening diseases, including advanced cancer [1]. However, graft-related complications, particularly infections, occur in up to 4% of cases, causing major morbidity and mortality [2–7].

Managing vascular graft infection is challenging. Antibiotics alone is frequently insufficient requiring graft removal, and revascularization [8]. While extra-anatomic bypasses were once the standard approach, in situ reconstruction has become favoured today [9]. Nonetheless, in contaminated fields, especially in the presence of secondary aortoenteric fistula, extra-anatomic bypass remains a viable option [10, 11]. Aortoenteric fistula mortality rates reach up to 57%.

This case highlights diagnostic challenges and management of a 27-year-old woman with aortoenteric erosion 19 years after aortic reconstruction.

Case report

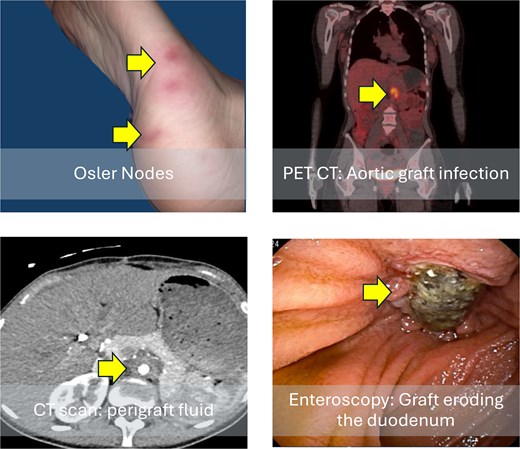

A 25-year-old female presented to the outpatient clinic with recurrent, red, tender, and painful lesions on the plantar region of the right foot, which appeared every 15 days, accompanied by malaise and fever, occurring 1 month after initiation of methotrexate therapy. The plantar lesions were diagnosed by dermatologists as Osler nodes (Fig. 1). Consequently, methotrexate was discontinued, and investigations for potential septic embolization sources initiated.

Clinical and radiological findings at patient admission. Osler nodes (red, tender, painful lesions on the plantar region of the right foot); computed tomography scan shows perigraft fluid; positron emission tomography (PET) scan with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose increased metabolic activity in the graft region in axial; and image of an enteroscopy showing the graft eroding the third portion of the duodenum.

The patient’s medical history included three abdominal surgeries: a major surgery to resect a ganglioneuroma affecting the abdominal aorta and the left kidney, where an aortic reconstruction with a Dacron graft (age 8), a cholecystectomy (age 21), and a laparotomy for acute abdominal obstructive syndrome, with segmental enterectomy and a sigmoid suture (age 23). At age 22 the patient developed a multifocal osteomyelitis involving the femur and tibia, with negative cultures. Nonspecific pulmonary imaging findings and a sputum rapid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positive for traces of Mycobacterium tuberculosis led to the diagnosis of tuberculosis. She had rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol for one year, but persisted with clinical symptoms and elevated inflammatory markers. A hypothesis of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis was considered and methotrexate was started.

After echocardiogram resulted negative for endocarditis, computer tomography (CT) scan revealed a perigraft collection. A positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) with 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose scan revealed an infection at the site of the previous aortic reconstruction. Endoscopy was normal, and peripheral blood cultures were negative. Perigraft fluid culture (obtained under CT guidance) resulted negative. After multidisciplinary meeting it was decided for conservative treatment and the patient was discharged on sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim.

After 6 months, the patient had an episode of bacteremia, receiving vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam for 2 weeks. She remained asymptomatic and was discharged with teicoplanin and ertapenem for 6 months. After that, the patient remained without antibiotic therapy.

After 2 years of conservative treatment, the patient had abdominal pain, fatigue, weight loss, intermittent fever, and an episode of moderate haematemesis. A CT scan revealed an aortoduodenal fistula, confirmed with an enteroscopy. In this context, a Klebsiella aerogenes susceptible only to carbapenems, polymyxins, and aminoglycosides was isolated in peripherical blood cultures.

Vancomycin and piperacillin–tazobactam were initiated, and the patient underwent a right axillary-to-femoral bypass using a 7-mm ring-reinforced expanded polytetrafluoroethylene graft. Immediately afterward, a median laparotomy was performed, the infected aortic graft was removed, and the infrarenal aorta was closed with Prolein 3–0 suture, preserving the integrity of the aortic bifurcation. A partial duodenectomy with duodenojejunal anastomosis was performed. At the end of surgery, distal pulses were palpable bilaterally, and limb perfusion was satisfactory.

The following day, the patient experienced haemodynamic deterioration, requiring epinephrine (0.3mcg/kg/h) and showing worsening perfusion of the left lower limb, despite the axillofemoral bypass remained patent. A femoral-femoral bypass was performed.

The patient remained in the ICU for 15 days and was discharged in good condition after 18 days of hospitalization. Culture of the explanted graft was positive for multidrug-sensitive Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli (multisensitive), and Candida Albicans. The fungal pathogen was isolated after hospital discharge, and due to clinical stability, it was not treated. At discharge, she was prescribed ciprofloxacin and later it was exchanged to levofloxacin for the past year.

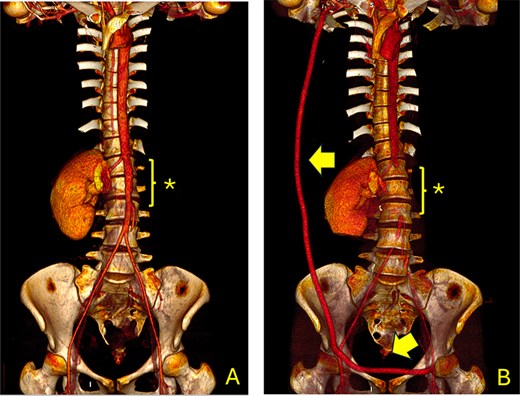

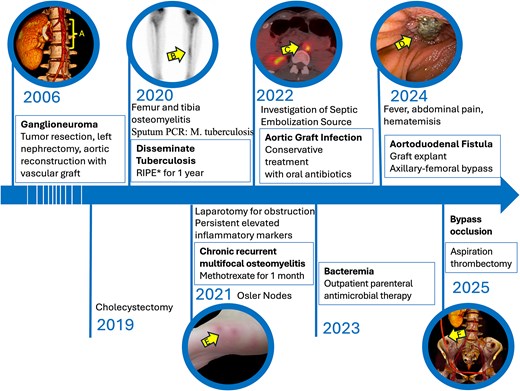

Eighteen months postoperatively, she underwent an aspiration thrombectomy due to acute graft thrombosis. At 24 months of follow-up, she remains free of bacteremia, with a patent bypass as shown in Fig. 2. A timeline in shown in Fig. 3.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) showing the aorta and iliac arteries. (A) Pre-operative CTA shows the area of the previous aortic graft (*); (B) Post-operative CT scan shows the axillofemoral bypass (arrow) and the aortic ligation (*).

Timeline of patient’s symptoms, signs, diagnosis and interventions. (A) Computed tomography (CT) scan highlighting the region of the aortic graft. (B) Bone scan revealing an osteogenic lesion in the left tibia; *RIPE: Rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. (C) Positron emission tomography CT scan with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose indicating infection of the aortic graft. (E) Enteroscopy showing erosion of the duodenal wall. (E) Osler nodes in the patient’s foot. (F) CT scan depicting the axillobifemoral bypass.

Discussion

This report describes a 27-year-old patient who developed aortoduodenal erosion 19 years after an aortic reconstruction. Antibiotic therapy was effective for 2 years until the patient developed an aortoduodenal erosion, requiring graft removal, aortic ligation, and duodenectomy. Reconstruction was performed with an axillobifemoral bypass.

Conservative management of aortic graft infections is generally reserved for high-risk cases [10, 12, 13]. In this patient, surgical difficulties were anticipated due to three prior laparotomies, with limited information on initial tumour resection and aortic reconstruction. Although case series report a 30-day mortality of 100% with conservative therapy [10], our patient remained largely asymptomatic on antibiotics for 2 years. This is consistent with a retrospective study of 50 patients, which showed acceptable outcomes with microbiological-directed antibiotics and biofilm eradication [12].

In suitable surgical candidates, management typically involves the complete removal of the infected graft [10]. Historically, extra-anatomic reconstruction was preferred; however, it carries risks such as stump blowout and occlusion. Consequently, in situ reconstruction has become the preferred approach [10].

However, in this case, an axillofemoral bypass was selected due to a severely infected surgical site, with an aortoduodenal erosion and resistant bacteria identified. This choice is supported by data from a systematic review of 1467 patients showing lower mortality with this approach (31%) versus 47% for in situ reconstruction [11].

Nevertheless, there are concerns regarding the durability of this bypass in a young patient, prompting the consideration of elective in situ reconstruction if the bypass results in frequent reoperations. However, evidence suggests that femorofemoral bypass procedures are safe, with few reported infections [14–16], with a secondary patency rate of 99% over 4 years [16].

The description of this case is limited by fragmented follow-up data, limited details on initial procedure and delaying suspicion of graft infection.

Despite this, the case emphasizes the need for patient education, and vigilance in vascular graft management. Graft infection should be considered in the differential diagnosis, even years post-surgery. Individualized care and multidisciplinary management are vital for improved outcomes.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no disclosures.

Funding

No funding was provided.

References

- aorta

- osler's node

- bacteremia

- aortoenteric fistula

- fatigue

- fever

- pathologic fistula

- child

- follow-up

- gangliocytoma

- osteomyelitis

- reconstructive surgical procedures

- surgical procedures, operative

- tissue transplants

- medical history

- neoplasms

- positron

- aortoplasty

- axillofemoral bypass

- graft infections

- conservative treatment

- aortic graft infection