-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ziad A Bataineh, Abdullah S Al-Darwish, Sumaiah Alkhulaifi, Thekraiat M Al Quran, Tension gastrothorax in a late-presenting congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a case report and review of the literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf750, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf750

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), a rare but potentially life-threatening anomaly resulting from incomplete diaphragm closure during fetal development, typically presents neonatally but can rarely manifest later in infancy as tension gastrothorax—a critical condition of intrathoracic gastric herniation and distension causing severe respiratory distress and mediastinal shift; we describe a 2-month-old male infant who developed sudden dyspnea and mediastinal shift due to a left-sided Bochdalek hernia with a distended stomach occupying the thoracic cavity, requiring emergent laparotomy with gastric decompression and defect repair using non-absorbable sutures, leading to full lung re-expansion and recovery; this case highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of late-presenting CDH complicated by tension gastrothorax, the importance of distinguishing it from other causes of respiratory distress, and emphasizes that prompt recognition, timely decompression, and surgical repair are vital for favorable outcomes, urging clinicians to maintain high suspicion when imaging reveals an air-filled hemithorax in distressed infants.

Introduction

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) results from incomplete fusion of the pleuroperitoneal membranes during fetal development, leading to a defect that permits herniation of abdominal organs into the thoracic cavity [1, 2]. Most cases are diagnosed prenatally or immediately after birth, with an estimated survival rate of 67% [3]. The incidence is ~0.8y or imme 000 live births [1, 4]. Tension gastrothorax, a rare but severe complication of CDH, occurs when the stomach herniates into the thorax and becomes distended due to volvulus or obstruction, causing mass effect, lung collapse, and mediastinal shift [5, 6].

This report describes a rare presentation of tension gastrothorax in a 2-month-old infant with undiagnosed CDH, emphasizing the diagnostic pitfalls and surgical management required.

Case presentation

A 2-month-old male infant, born full term via cesarean section, presented to the pediatric emergency department with acute dyspnea and feeding intolerance for 2 days. He had a history of unexplained respiratory distress requiring pediatric intensive care admission one month prior.

On admission, the infant was irritable, hypoactive, dehydrated, and in severe respiratory distress. Vital signs revealed tachycardia and tachypnea. Physical examination showed absent breath sounds over the left lung field and heart sounds more prominent on the right, consistent with rightward mediastinal shift. The trachea was deviated to the right.

Laboratory workup demonstrated leukocytosis with elevated C-reactive protein and lactate. Electrolytes and blood glucose were within normal limits.

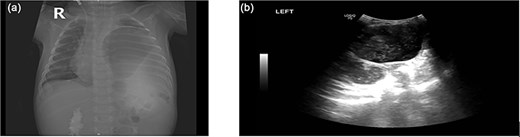

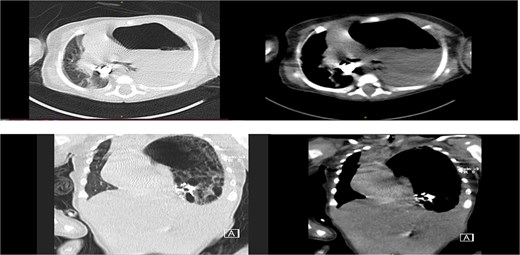

Chest radiograph showed an opaque left hemithorax with mediastinal shift to the right and a large air-fluid level, raising suspicion for diaphragmatic hernia with gastric herniation (Fig. 1a). Abdominal ultrasound revealed a cystic structure in the left thorax consistent with the stomach (Fig. 1b). Computed tomography confirmed a left posterolateral diaphragmatic defect with herniation of the stomach into the thorax, consistent with Bochdalek hernia and tension gastrothorax (Fig. 2).

(a) Opacified left hemithorax with shifting of the mediastinum to the right side due to possible left diaphragmatic hernia also there is right perihilar infiltrate. (b) US showed: Large cystic structure noted in the left side of chest likely stomach, diaphragmatic hernia cannot be ruled out.

Axial, coronal CT chest revealed: Left diaphragmatic hernia (Bochdalek hernia) stomach herniation to the left hemithorax with a shift in the mediastinum.

Operative management

Emergency laparotomy was performed. Intraoperatively, a left posterolateral (Bochdalek) defect was identified. The stomach was grossly distended and herniated through the defect into the thorax with a single mesoaxial twist, compressing the left lung and shifting the mediastinum. The gastroesophageal junction was in place. A large orogastric tube was passed to decompress the stomach, allowing safe reduction into the abdomen. The diaphragmatic defect was repaired primarily with interrupted non-absorbable sutures after refreshing the defect margins.

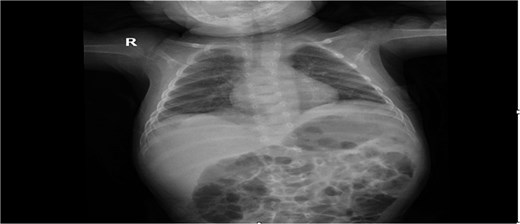

Postoperative recovery was uneventful. Chest radiography showed full re-expansion of the left lung and normalization of the mediastinal position (Fig. 3).

Post-op chest X-ray was normal and show a full expansion of the left lung, with normal diaphragm, normal stomach gas in the intraperitoneal region.

Discussion

CDH is a significant developmental anomaly that results from incomplete fusion of the pleuroperitoneal membranes during the embryonic period, typically between the 8th and 10th weeks of gestation [1, 2]. The most common type, the Bochdalek hernia, accounts for >90% of cases and occurs posterolaterally, more frequently on the left side due to the protective effect of the liver on the right hemidiaphragm [2, 3]. While the majority of CDH cases present during the neonatal period with severe respiratory distress and pulmonary hypoplasia, approximately 5rrupted non-abso later in infancy or childhood [4, 7, 8]. These late-presenting cases pose a unique diagnostic challenge because their symptoms are often subtle, intermittent, or attributed to more common pediatric conditions such as pneumonia, bronchiolitis, or gastrointestinal reflux [7, 9].

Tension gastrothorax is a rare but life-threatening complication of CDH and is defined as herniation of the stomach into the thoracic cavity with progressive distension due to volvulus or obstruction, creating a space-occupying mass that compresses the ipsilateral lung and shifts the mediastinum contralaterally [4–6]. The mechanism typically involves gastric volvulus, which may be organoaxial or mesoaxial, leading to closed-loop obstruction and progressive gastric dilation [5]. This results in severe respiratory distress, compromised venous return, and hemodynamic instability, mirroring the pathophysiology of a tension pneumothorax [5, 6].

Early recognition is critical yet challenging. Clinical signs include sudden-onset dyspnea, cyanosis, tachypnea, asymmetric breath sounds, and tracheal deviation away from the affected side [4, 5]. Misdiagnosis as pneumothorax or pleural effusion is common, especially when chest radiography reveals an air-filled or fluid-filled structure in the hemithorax with mediastinal shift [6, 7]. Inappropriately placing a chest tube in this setting may lead to gastric perforation or iatrogenic contamination of the pleural space [4–6]. Therefore, when tension gastrothorax is suspected, insertion of a nasogastric or orogastric tube to decompress the stomach should be the first-line intervention, followed by confirmatory imaging and emergent surgery [5, 6].

Radiographic features suggestive of tension gastrothorax include a large air-fluid level occupying the hemithorax, collapsed lung tissue, and contralateral mediastinal shift [5, 7]. A distended stomach may sometimes be misinterpreted as a large pneumothorax or cystic lung lesion [5]. An upper gastrointestinal contrast study or computed tomography can clarify the diagnosis by delineating the herniated viscera and confirming the diaphragmatic defect [5–7].

The definitive treatment of tension gastrothorax is urgent surgical intervention. Initial resuscitation includes oxygenation, fluid resuscitation, and prompt gastric decompression with a large-bore nasogastric or orogastric tube [5, 6]. Emergent laparotomy is preferred over thoracotomy because it allows safe reduction of the herniated viscera, detorsion of the stomach if volvulus is present, inspection for ischemia, and repair of the diaphragmatic defect [2, 5, 6]. In our case, the stomach was found to be herniated and rotated with a mesoaxial twist, producing a one-way valve effect that caused progressive distension and mediastinal shift. Primary repair with non-absorbable interrupted sutures remains the standard for small to moderate defects [1–3]. In larger defects, patch repair may be required [1, 2].

Awareness of this rare but critical condition is vital for pediatric surgeons, emergency physicians, and pediatricians alike. Timely diagnosis and intervention can be life-saving and are associated with excellent outcomes if managed appropriately [4, 6]. Long-term follow-up is warranted to monitor for recurrence, pulmonary complications, or gastroesophageal reflux, which may occur in a subset of patients [2, 9, 10].

In conclusion, this case reinforces the importance of considering late-presenting CDH complicated by tension gastrothorax in any infant with unexplained acute respiratory distress, especially in the context of previous intermittent respiratory or feeding difficulties [5, 6, 9]. A high index of suspicion, careful radiographic interpretation, and prompt surgical management are essential to prevent unnecessary morbidity and mortality [11, 12].

Conclusion

This case highlights the importance of including tension gastrothorax in the differential diagnosis for infants with acute respiratory distress and radiological evidence of an air-filled structure in the hemithorax. Prompt radiographic evaluation and emergent surgical intervention are critical for favorable outcomes.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

References

Han XY, Dassios T, Ali K, et al.

Puligandla PS, Grabowski J, Austin M, et al.

Ali K, Dassios T, Khaliq SA, et al.

Chiu CY, Chen YC, Wu JR, et al.