-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Reem Khabbaza, Ayat Shawish, Alaa Mahmoud, Mohammad Adib Houreih, Moatasem Hussein Al-janabi, Fouz Hassan, A rare case of hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung initially presenting as a painful skin nodule, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf708, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf708

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the lung (HAL) is a rare and aggressive subtype of pulmonary adenocarcinoma, with cutaneous metastasis being an uncommon clinical manifestation. A 49-year-old male presented with a painful, nodular skin lesion on the upper back. Histopathological examination confirmed it as a cutaneous metastasis of HAL. Subsequent imaging revealed a large primary tumor in the left lung and widespread metastatic disease. Remarkably, the skin lesion was the initial and only presenting feature. This case illustrates the variable clinical presentation of HAL and underscores the need for thorough evaluation of atypical skin lesions.

Introduction

Hepatoid adenocarcinoma (HAC) is a rare and aggressive neoplasm that resembles hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in both morphology and biological characteristics, despite arising in extrahepatic organs. It has an annual incidence of 0.58 to 0.83 cases per million people [1, 2]. The most frequent site of origin is the stomach (accounting for ~63% of cases), followed by the ovaries, pancreas, gallbladder, uterus, and rarely the lungs [3, 4]. HAC of the lung (HAL) represents a ~2.5% of all HAC cases and primarily affects middle-aged male heavy smokers. It is often diagnosed at an advanced stage and associated with a poor prognosis [5]. Common metastatic sites include the lymph nodes (57.5%) and the liver (46.3%) [6].

Cutaneous metastases occur in ~5.3% of all cancers, but in only 0.8% of lung cancers as the initial manifestation [7, 8]. We present a rare case of HAL in which a painful skin lesion was the only presenting symptom.

Case presentation

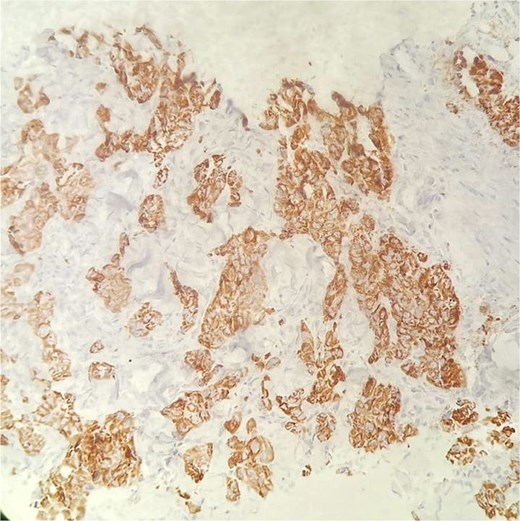

A 49-year-old male with a 20-pack-year smoking history and occasional alcohol consumption presented with a painful, nodular skin lesion on his upper back. The lesion had been present for ~1 month and had progressively increased in size. Clinically, it appeared as a solitary, firm, erythematous nodule with central ulceration and overlying necrotic crust, measuring ~1.5 × 1 cm and surrounded by a violaceous inflammatory halo (Fig. 1). A partial excisional biopsy was obtained from the center of the lesion. Histopathological examination using hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a poorly circumscribed, infiltrating tumor within the dermis. The tumor is composed of cords and nodules of atypical cells dissecting between collagen bundles, with focal areas of gland formation. The tumor extends into the subcutaneous adipose tissue and surrounding soft tissue in an irregular infiltrative pattern. The findings confirmed invasive adenocarcinoma (Fig. 2), prompting further evaluation to assess for metastatic spread. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated a lobulated mass with heterogeneous enhancement centered at the left pulmonary hilum, invading adjacent bronchi and vascular structures (Fig. 3A). Multiple hypodense lesions in the liver were consistent with hepatic metastases (Fig. 3B). Additionally, numerous lytic bone lesions were noted involving the ribs, vertebral bodies, sternum, and right pubic bone, indicating widespread skeletal metastases.A positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) scan was not performed due to lack of availability in Syria. Bronchoscopy revealed complete obstruction of the left upper lobe bronchus, and a biopsy was obtained from the lesion. Histopathological examination demonstrated features consistent with invasive high-grade HAC, characterized by large polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli, resembling HCC morphology (Fig. 4). To further support the diagnosis, immunohistochemical staining was performed. The tumour cells showed strong positivity for CK7, HepPar-1, and CK19 (Fig. 5), and were negative for TTF-1, Napsin-A, p40, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and Glypican-3. Serum AFP level was within normal limits. This immunoprofile supports the diagnosis of HAC of pulmonary origin. In addition, immunohistochemical staining for HepPar-1 was performed on the biopsy from the subcutaneous metastasis, which also showed positive staining (Fig. 6). This finding further supports the lung as the primary site of the hepatoid carcinoma, given the matching immunophenotype between the primary lung tumour and the cutaneous metastasis.

Clinical image showing an erythematous, firm nodule with a central necrotic crust located on the upper back.

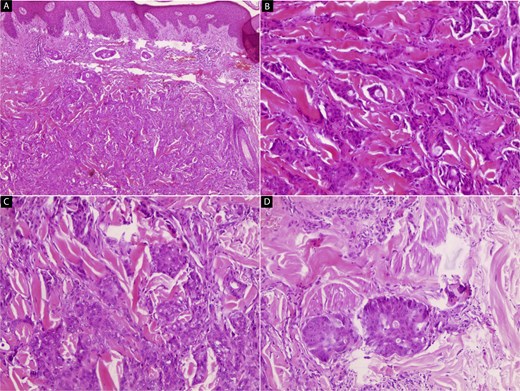

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained microscopic images of the skin lesion. (A, B) Low-power views reveal a poorly circumscribed, infiltrative tumor within the dermis. The tumor is composed of irregular cords and nests of atypical cells dissecting between collagen bundles, with focal glandular differentiation (40× and 100×). (C, D) High-power views show large polygonal tumor cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and pleomorphic, vesicular nuclei containing prominent nucleoli, resembling hepatocytic morphology. The tumor exhibits irregular infiltration into the subcutaneous fat and adjacent soft tissue (200× and 400×).

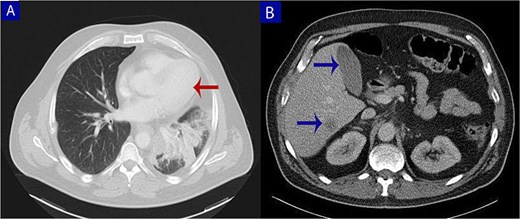

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. (A) Axial chest CT shows a lobulated mass (arrow) with heterogeneous enhancement centered at the left pulmonary hilum, invading adjacent bronchial and vascular structures. (B) Abdominal CT reveals multiple hypodense lesions in the liver (arrows), consistent with hepatic metastases.

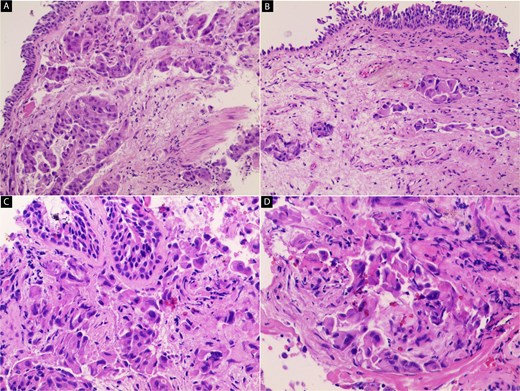

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections of the primary lung tumor. (A, B) Low-power views show an infiltrative tumor composed of irregular nests and trabeculae of malignant cells within desmoplastic stroma. The tumor lacks a well-defined boundary and infiltrates surrounding connective tissue (40×). (C, D) High-power views demonstrate large polygonal tumor cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and centrally located pleomorphic nuclei with prominent nucleoli. These cells exhibit a hepatoid (hepatocyte-like) morphology (100× and 200×).

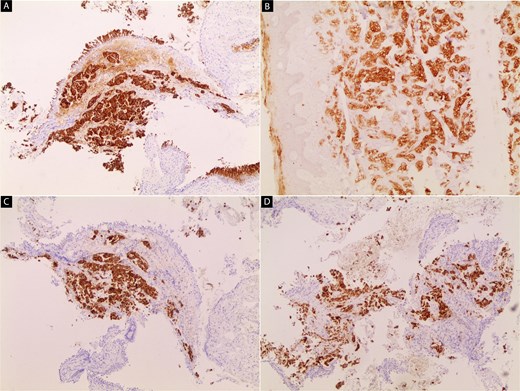

Immunohistochemical staining of the primary lung tumor.

(A) Tumour cells show strong cytoplasmic positivity for cytokeratin 7 (CK7).

(B) Diffuse positivity for cytokeratin 19 (CK19) is observed in the tumor cells. (C, D) tumor cells exhibit strong cytoplasmic staining for hepatocyte paraffin 1 (HepPar-1).

Immunohistochemical staining for HepPar-1 on the skin metastasis biopsy, showing positive cytoplasmic staining in tumor cells.

Approximately ten days after the initial skin lesion, a second painless scalp nodule with central ulceration appeared (Fig. 7). However, biopsy could not be performed due to the patient’s rapid clinical deterioration. Clinical and histopathological images were obtained and will be included as supplementary material. Unfortunately, the patient passed away before any oncologic treatment could be initiated.

Clinical image showing a painless, ulcerated scalp nodule that appeared ten days after the initial skin lesion.

Discussion

HAL is a rare and aggressive subtype of pulmonary adenocarcinoma characterized by hepatocellular differentiation, with or without elevated serum AFP levels [3].

Distinguishing HAL from metastatic HCC remains a significant diagnostic challenge. In this case, immunohistochemistry played a crucial role; the tumor cells were positive for CK7, Hep-Par1, and CK19, and negative for TTF-1, Napsin-A, p40, AFP, and Glypican-3. This immunoprofile supports a primary pulmonary origin and helps exclude metastatic HCC.

Radiologically, the largest mass was centered in the left upper pulmonary hilum, while the hepatic lesions were smaller and more scattered—consistent with secondary liver metastases rather than a primary hepatic tumor.

Although HAL has been reported to most commonly affect the right upper lobe (in 52.9% of documented cases) [3], our patient presented with a dominant lesion in the left hilar region.

To date, only two cases of HAL with cutaneous metastasis have been reported. Notably, the initial and only manifestation in our case was a solitary, painful skin nodule that led directly to diagnosis. In contrast, the previously reported case [9], involved multiple asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules that followed nonspecific lumbar discomfort. These differences highlight the need to consider malignancy in patients presenting with isolated painful skin lesions, even in the absence of systemic symptoms.

Cutaneous metastases are more commonly associated with tumors arising from the upper lobes of the lungs, likely due to hematogenous spread through regional vascular and lymphatic pathways [10]. Although they can occur anywhere, they tend to involve richly vascularized regions such as the scalp, chest, and back [8, 10]. In our case, the first lesion was located on the upper back, followed by a second painless ulcerated nodule on the scalp—findings that are consistent with previous reports. Unfortunately, due to the patient’s rapid clinical deterioration, biopsy of the scalp lesion could not be performed.

Cutaneous metastases in HAL are exceedingly rare, and data on their incidence are lacking due to the rarity of the disease itself. Their presence typically indicates advanced-stage malignancy and correlates with poor prognosis [11].

Currently, there is no standardized treatment protocol for HAL. Available options include surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Nonetheless, prognosis remains poor, with reported median survival ranging from 10 to 18 months [1]. In this case, the patient died before any treatment could be initiated, reflecting the aggressive nature and rapid progression of the disease.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of HAL initially manifesting as a solitary, painful, and rapidly enlarging cutaneous nodule. This atypical presentation underscores the need to consider metastatic malignancy in the differential diagnosis of unusual skin lesions, even in patients with no known primary tumor. Early identification and comprehensive diagnostic evaluation are essential to ensure timely and appropriate management, particularly in aggressive tumors such as HAL.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflict of interest.

Funding

There was no funding for this publication.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval was required for this publication.

Consent

Informed and written consent from the patient was taken prior to publication.