-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dhruv Gandhi, Shivangi Tetarbe, Preeti Sheth, Ira Shah, Penoscrotal swelling as a presentation of Crohn’s disease, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf704, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf704

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Metastatic Crohn’s disease (MCD) is a rare extraintestinal manifestation of Crohn’s disease (CD), particularly in pediatric patients. It refers to cutaneous involvement at areas distant and non-contiguous from the bowel. We present a boy with a 1.5-year history of perianal lesions, penoscrotal swelling, and intermittent hematochezia. Examination revealed hepatosplenomegaly, perianal erythematous plaques, and inguinoscrotal swelling. Biopsy of the scrotal skin revealed non-caseating granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of MCD. Stool calprotectin was elevated, however, gastrointestinal biopsies were suggestive of indeterminate colitis. Initial management with symptomatic treatment provided limited relief, and he was later started on oral immunomodulators. This case highlights MCD as a rare but significant initial presentation of CD in pediatric patients and emphasizes the need for increased awareness of MCD in children with unexplained cutaneous lesions.

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic relapsing granulomatous disorder which may involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract, typically involving the ileum and the proximal colon [1, 2]. Pediatric patients typically present with abdominal pain, loss of weight, fever, bloody or non-bloody diarrhea, failure to thrive, growth impairment, and delayed puberty [2]. Extra-intestinal manifestations in CD are common, with the skin being reported as the most common site of involvement. Cutaneous manifestations in CD are commonly due to direct extension of the intestinal disease to the adjoining skin in the form of perianal abscesses, fistula, fissures, or ulcers. However, rarely, there may be cutaneous involvement in such patients at areas non-contiguous and distant from the bowel, a condition described as metastatic CD (MCD). MCD typically presents with red-to-purple coloured plaques or nodules in the intertriginous area, face, limbs, and genital region [3]. We present a boy with a penoscrotal swelling who was diagnosed with MCD of the scrotal skin on a cutaneous biopsy.

Case

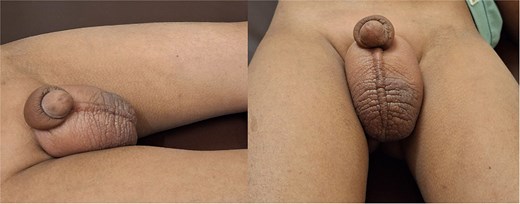

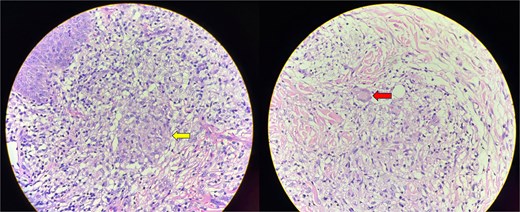

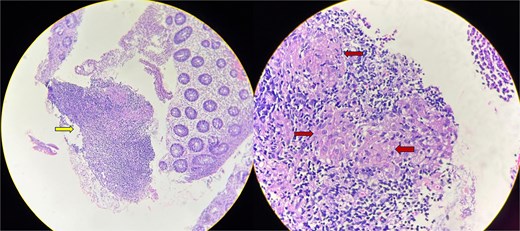

A 6.5-year-old boy presented in July 2024 with perianal skin lesions, scrotal and penile swellings and occasional passage of blood in stool for 1.5 years. On presentation, his height was 113 cm (between 10th and 25th percentile according to the Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) charts), weight was 18.7 kg (between 25th and 50th percentile according to the IAP charts), and head circumference was 44 cm. On examination, he had microcephaly, hepatosplenomegaly, perianal erythematous plaques, and an erythematous swelling in the inguinoscrotal region (Fig. 1). Scrotal ultrasound showed diffuse scrotal wall edema with no funiculitis or epididymo-orchitis. Scrotal skin biopsy showed focal epidermal thinning and an epidermal neutrophilic infiltrate. Dermis and subcutaneous tissue showed an inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphoplasmacytes and foamy macrophages, ill-defined granulomas with epithelioid-like cells, multinucleated giant cells and no evidence of necrosis (Fig. 2). Stool examination found eight erythrocytes/high power field (HPF) and 30 leukocytes/HPF. Stool calprotectin was 146 g/gm. Abdominal ultrasound showed hepatomegaly with coarse echotexture, splenomegaly, terminal ileal thickening (4.5 mm), and reactive subcentimetric mesenteric lymphadenopathy. Other investigations are shown in Table 1. Ileocolonoscopy showed caecal pitting and a solitary rectal ulcer which was excised by snare. Esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy found white spots in the duodenum. Colon biopsy showed mucosal ulceration, mixed inflammation in the lamina propria, crypt branching, cryptitis, few ill-defined epithelioid cell granulomas, and no evidence of necrosis (Fig. 3). Duodenal biopsy showed chronic lymphoplasmacytic inflammation in the lamina propria and maintenance of the crypt:villous ratio. Xpert MTB/Rif of the skin tissue, colon tissue, stool, and gastric lavage was negative. He received symptomatic treatment with oral colchicine, oral hydroxyzine, mupirocin ointment for local perianal application, fluticasone cream for scrotal application, and probiotics. At the 6-month follow-up, his inguino-scrotal swelling and perianal rash was persistent. The stool calprotectin in January 2024 was 716.46 g/gm. Repeat abdominal ultrasound showed mildly edematous bowel loops. Scrotal ultrasound in January 2025 showed diffuse chronic scrotal wall thickening with minimal edema and inflammatory changes. In view of the cutaneous histopathological findings, he was diagnosed with scrotal CD with indeterminate colitis and was started on oral immunomodulators and asked to follow-up after 1 month.

Skin biopsy showing an inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages. Ill-defined, non-caseating granulomas with epithelioid cells are present (arrow in the first image). Langhans-type of multinucleated giant cells are seen (arrow in the second image).

| Parameters . | July 2023 . | January 2024 . | Reference ranges . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | 9.6 | 10.7 | 11.5–15.5 |

| White blood cell count (cells/cumm) | 7900 | 10 840 | 5000–13 000 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (cells/cumm) | 4819 | 7696 | 2000–8000 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/cumm) | 2528 | 2602 | 1000–5000 |

| Platelets (106 cells/cumm) | 3.9 | 3.68 | 1.50–4.50 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 22 | 17 | 0–15 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 0.6 | < 5 | |

| ALT (IU/L) | 7 | 15 | < 41 |

| AST (IU/L) | 10 | 39 | < 41 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 199 | 304 | 142–335 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.2 | 0.0–1.10 | |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.1 | 0.0–0.60 | |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.1 | 0.10–0.80 | |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 9 | 5–18 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.38 | 0.3–0.59 | |

| Serum total protein (gm/dl) | 7.5 | 7.9 | 6.0–8.3 |

| Serum albumin (gm/dl) | 3.9 | 4.4 | 3.8–5.4 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 15.5 | 15.8 | 10.3–13.1 |

| INR | 1.35 | 1.38 | 0.8–1.2 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | 9.4 | 8.8–10.8 | |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dl) | 3.7 | 3.0–5.4 |

| Parameters . | July 2023 . | January 2024 . | Reference ranges . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | 9.6 | 10.7 | 11.5–15.5 |

| White blood cell count (cells/cumm) | 7900 | 10 840 | 5000–13 000 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (cells/cumm) | 4819 | 7696 | 2000–8000 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/cumm) | 2528 | 2602 | 1000–5000 |

| Platelets (106 cells/cumm) | 3.9 | 3.68 | 1.50–4.50 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 22 | 17 | 0–15 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 0.6 | < 5 | |

| ALT (IU/L) | 7 | 15 | < 41 |

| AST (IU/L) | 10 | 39 | < 41 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 199 | 304 | 142–335 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.2 | 0.0–1.10 | |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.1 | 0.0–0.60 | |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.1 | 0.10–0.80 | |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 9 | 5–18 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.38 | 0.3–0.59 | |

| Serum total protein (gm/dl) | 7.5 | 7.9 | 6.0–8.3 |

| Serum albumin (gm/dl) | 3.9 | 4.4 | 3.8–5.4 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 15.5 | 15.8 | 10.3–13.1 |

| INR | 1.35 | 1.38 | 0.8–1.2 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | 9.4 | 8.8–10.8 | |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dl) | 3.7 | 3.0–5.4 |

Note: ESR- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP- C-reactive protein, ALT- Alanine aminotransferase, AST- Aspartate aminotransferase, ALP- Alkaline phosphatase, BUN- Blood urea nitrogen, INR- International normalised ratio.

| Parameters . | July 2023 . | January 2024 . | Reference ranges . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | 9.6 | 10.7 | 11.5–15.5 |

| White blood cell count (cells/cumm) | 7900 | 10 840 | 5000–13 000 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (cells/cumm) | 4819 | 7696 | 2000–8000 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/cumm) | 2528 | 2602 | 1000–5000 |

| Platelets (106 cells/cumm) | 3.9 | 3.68 | 1.50–4.50 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 22 | 17 | 0–15 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 0.6 | < 5 | |

| ALT (IU/L) | 7 | 15 | < 41 |

| AST (IU/L) | 10 | 39 | < 41 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 199 | 304 | 142–335 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.2 | 0.0–1.10 | |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.1 | 0.0–0.60 | |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.1 | 0.10–0.80 | |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 9 | 5–18 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.38 | 0.3–0.59 | |

| Serum total protein (gm/dl) | 7.5 | 7.9 | 6.0–8.3 |

| Serum albumin (gm/dl) | 3.9 | 4.4 | 3.8–5.4 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 15.5 | 15.8 | 10.3–13.1 |

| INR | 1.35 | 1.38 | 0.8–1.2 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | 9.4 | 8.8–10.8 | |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dl) | 3.7 | 3.0–5.4 |

| Parameters . | July 2023 . | January 2024 . | Reference ranges . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | 9.6 | 10.7 | 11.5–15.5 |

| White blood cell count (cells/cumm) | 7900 | 10 840 | 5000–13 000 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (cells/cumm) | 4819 | 7696 | 2000–8000 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/cumm) | 2528 | 2602 | 1000–5000 |

| Platelets (106 cells/cumm) | 3.9 | 3.68 | 1.50–4.50 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 22 | 17 | 0–15 |

| CRP (mg/dl) | 0.6 | < 5 | |

| ALT (IU/L) | 7 | 15 | < 41 |

| AST (IU/L) | 10 | 39 | < 41 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 199 | 304 | 142–335 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.2 | 0.0–1.10 | |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.1 | 0.0–0.60 | |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.1 | 0.10–0.80 | |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 9 | 5–18 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.38 | 0.3–0.59 | |

| Serum total protein (gm/dl) | 7.5 | 7.9 | 6.0–8.3 |

| Serum albumin (gm/dl) | 3.9 | 4.4 | 3.8–5.4 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 15.5 | 15.8 | 10.3–13.1 |

| INR | 1.35 | 1.38 | 0.8–1.2 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | 9.4 | 8.8–10.8 | |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dl) | 3.7 | 3.0–5.4 |

Note: ESR- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP- C-reactive protein, ALT- Alanine aminotransferase, AST- Aspartate aminotransferase, ALP- Alkaline phosphatase, BUN- Blood urea nitrogen, INR- International normalised ratio.

Colon biopsy showing mucosal ulceration and mixed inflammatory infiltrate (arrow in the first image). Poorly-defined epithelioid granulomas (arrows in the second image) with no evidence of necrosis seen.

Discussion

MCD has been rarely reported in current literature, with <100 documented cases, and even fewer cases in the pediatric population [4, 5]. MCD is commonly seen between the ages of 20 and 40 years. In children, the most common age group involved is 10–14 years [4]. MCD is believed to result from immunological dysregulation resulting in the migration of immune cells to the skin and local cutaneous cytokine-mediated inflammation. While the exact pathophysiology remains unclear, similarities to the immunological mechanisms underlying CD, suggest that MCD represents a form of systemic CD activity [5].

Most adult patients of MCD have prior well-documented intestinal CD. However, in pediatric patients, as in our patient, MCD tends to be the initial presentation prior to the diagnosis of intestinal disease, adding to the difficulty in diagnosing such patients. Genital MCD tends to present in children prior to the onset of intestinal CD as seen in our patient, whereas non-genital MCD has never been reported in children as the initial presentation [4]. Clinically, MCD may present with solitary or multiple lesions including erythematous plaques, nodules, or ulcers. A variety of sites may be involved including the extremities, trunk, face, buttocks, and genitals [4, 5]. A review of MCD cases in children concluded that the most common site of involvement in girls was the labia (65%) and in boys was the penoscrotal region (78.6%) [4].

The diagnosis of MCD requires a combination of clinical examination, histopathology, and exclusion of other differential diagnoses. A key feature of MCD is the presence of non-caseating granulomatous inflammation in the skin at sites distant from the gastrointestinal tract without any direct continuity. This distinguishes MCD from reactive skin manifestations of CD, such as erythema nodosum, Sweet syndrome, and pyoderma gangrenosum, which have distinct histopathological features [3]. However, differentiating MCD from other granulomatous dermatoses such as sarcoidosis, foreign body reaction, mycobacteria, and fungal infections, can be challenging [4, 5]. Dermoscopy and imaging modalities, such as ultrasound or MRI, may assist in evaluating the extent of skin and subcutaneous involvement [5].

Management of MCD remains challenging due to its variable response to conventional treatments. First-line therapies typically involve topical/systemic corticosteroids. Immunomodulators, such as azathioprine and methotrexate, have shown variable success. In refractory cases, biologic agents, such as infliximab and adalimumab, have shown efficacy in controlling cutaneous disease. These agents, already widely used for CD, have demonstrated promising results in MCD by modulating systemic immune responses [4, 5]. Antibiotics such as metronidazole and dapsone have been reported to provide symptomatic relief in some cases [5]. Thalidomide also appears to be useful in such cases. In severe or refractory cases, localized surgical excision may be necessary. However, recurrence remains a concern, highlighting the need for ongoing systemic therapy and close dermatologic follow-up [5]. MCD prognosis varies based on disease severity and treatment response. While some cases resolve with appropriate therapy, others exhibit chronic, relapsing courses requiring long-term immunosuppression [5].

Author contributions

D.G. and S.T. did review of literature and wrote the manuscript. P.S. and I.S. reviewed and edited and the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicting interests to declare regarding this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Guarantor

Ira Shah is the guarantor for this manuscript.

Consent

Informed patient consent was obtained from the parent of the child.