-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Shubu Parajuli, Shruti Sah, Narendra Pandit, Malignant melanoma of the anal canal: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf700, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf700

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Anal melanoma is a rare and aggressive malignancy with early local invasion and high metastatic potential, leading to poor outcomes. Limited to case reports, the literature offers little guidance on standardized treatment. We report a case of a 71-year-old male with a year-long history of perianal pain and painful defecation, following decades of mild anal discomfort. He underwent hemorrhoidectomy for presumed hemorrhoids, but histopathology revealed invasive malignant melanoma. On presentation, per rectal exam showed perianal satellite nodules and black pigmentation of the anal canal. Imaging confirmed anal canal thickening with hepatic and pulmonary metastases. Given the advanced stage and positive margins, the patient was managed palliatively with systemic chemotherapy.

Introduction

Malignant melanoma of the anal canal is a rare and aggressive neoplasm, accounting for ⁓1% of all anorectal malignancies and 0.4%–1.6% of all melanomas [1]. Its clinical presentation often mimics benign conditions such as hemorrhoids or anal fissures, leading to delayed diagnosis and poor prognosis. This malignancy originates from melanocytes located between the anal transition zone and the dentate line, derived embryologically from the neural crest [2].

Unlike cutaneous melanoma, anorectal melanoma is not associated with ultraviolet exposure and most commonly involves the rectum, anal canal and the anal verge. While cutaneous melanomas frequently harbor N-ras mutations (especially at codon 61), such alterations are uncommon in mucosal melanomas. Diagnosis is confirmed via biopsy [3].

Satellite lesions defined as cutaneous or subcutaneous nodules within 2 cm of the primary tumor, representing early locoregional spread, are well-documented features of cutaneous melanoma but are rarely described in anorectal presentations [4–6]. Given its high invasiveness, anorectal melanoma responds poorly to both local therapies and radical surgery. Up to 60% of cases are misdiagnosed at first presentation, and over 70% present with metastatic disease [7]. The 5-year survival rate remains ⁓10%, with mean survival between 15 and 25 months [8]. Owing to its low incidence, evidence remains limited to individual case reports and small series [9].

We present a case of malignant melanoma of the anal canal with visible satellite lesions, contributing to the sparse existing literature.

Case presentation

A 71-year-old male presented to our center with chief complaints of persistent perianal pain and painful defecation for the past one year. He reported a 35-year history of dull, aching anal discomfort, which had worsened one year prior, prompting him to seek medical attention. At that time, hemorrhoids were diagnosed and he subsequently underwent hemorrhoidectomy four months later. He denied history of per-rectal bleeding.

Histopathological examination of the excised specimen revealed a proliferation of atypical epithelioid cells arranged in sheets and nests, extending to the resected base. The tumor cells exhibited marked pleomorphism, prominent eosinophilic nucleoli, finely dispersed chromatin, and abundant pale cytoplasm. Additionally, spindle-shaped cells, atypical mitotic figures, and bizarre cellular forms were identified. These findings were consistent with invasive malignant melanoma. The patient was referred to our center with histopathology report.

Upon presentation, vital signs were stable. General examination revealed pallor, without icterus, clubbing, cyanosis, or edema. Per rectal examination revealed multiple perianal satellite nodules, ⁓6 cm in total distribution, involving the anal verge and perianal region (Fig. 1a). Proctoscopy revealed blackish discoloration of the anal mucosa and a pigmented tumor within the anal canal (Fig. 1b).

(a) Clinical image showing multiple perianal satellite nodules ⁓6 cm in total distribution. (b) Proctoscopic image showing blackish discoloration of anal mucosa with pigmented tumor within anal canal.

Baseline investigations revealed a hemoglobin level of 9.82 g/dL, leukocyte count of 7810 cells/μL (neutrophils 73%); carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was 3.701 ng/mL. Renal function was normal. Coagulation profile showed PT of 12 s and INR of 0.9. Serum alkaline phosphatase was elevated at 232 U/L.

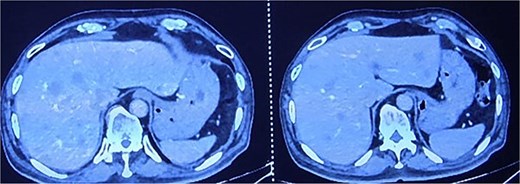

(1) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated enhancing circumferential wall thickening involving the anal canal and lower rectum, with obliteration of the intervening fat plane between the tumor and the prostate. Multiple peripherally enhancing lesions were identified in both hepatic lobes, suggestive of hepatic metastases (Fig. 2a). Several pleural-based pulmonary nodules were seen bilaterally, consistent with metastatic deposits (Fig. 2b).

CECT abdomen and pelvis showing hepatic metastasis and pulmonary metastasis.

Given the positive surgical margins, metastases, and patient’s financial constraints, a palliative management approach was adopted. The patient was started on systemic chemotherapy aimed at symptom control and delaying disease progression.

Discussion

Anorectal malignant melanoma (ARMM) is a rare and highly aggressive tumor, comprising ⁓0.05% of all colorectal and upto 4.6% of all anorectal malignancies [10]. Originating from melanocytes in the squamous or transitional zone of anal canal, ARMM often presents with nonspecific symptoms such as pain, a palpable mass, or altered bowel habits, frequently misdiagnosed as benign conditions such as hemorrhoids.

Histologically, ARMM may exhibit epithelioid or spindle cell morphology. Immunohistochemical staining with S-100, HMB-45, and Melan-A confirms the diagnosis [11]. In our patient, histopathology revealed classic malignant melanoma features including pleomorphism, atypical mitoses, and tumor infiltration to the resection margin.

Notably, the presence of perianal satellite lesions indicate locoregional spread associated with poor prognosis [12]. Imaging confirmed extensive local invasion with hepatic and pulmonary metastases, consistent with ARMM’s early lymphovascular dissemination.

While surgical resection (wide local excision or abdominoperineal resection) is the mainstay for localized disease, advanced cases like this one preclude curative surgery.

Immunotherapy, particularly checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting PD-1 such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and CTLA-4 pathways like ipilimumab have demonstrated promising results in mucosal melanoma cohorts, with improved response rates when used in combination [13, 14]. However, financial barriers limited access in our case, and the patient received palliative chemotherapy.

This case highlights the necessity for heightened clinical vigilance in patients with persistent anorectal symptoms and histopathological evaluation in all excised anorectal tissues.

Conclusion

Primary malignant melanoma of the anal canal with satellite lesions is exceedingly rare and aggressive. Often misdiagnosed as benign anorectal conditions, this malignancy presents late, limiting curative treatment. Early diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion, especially in patients with persistent perianal symptoms. Proctoscopy may reveal characteristic pigmentation, aiding detection. Surgery is often palliative. Routine histopathological evaluation of all anorectal specimens is crucial to avoid missed diagnoses.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.