-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hammoud Hamid, Muataz Aasi, Ahmad Yousef, Mohammed Alarsan, Muhammad Ghanem, Mais Alreem Basel Mohaisen, Mohamad Sibai, A rare primary occipitocervical hydatid cyst in a 13-year-old girl: a rare case report from Syria, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 9, September 2025, rjaf699, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf699

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Cervical hydatid cysts are extremely rare manifestations of Echinococcus granulosus, typically occurring in the liver or lungs. Their atypical appearance presents difficulties in diagnosis and may divert physicians from considering parasite causes. We report the case of a 13-year-old female who exhibited a painful occipitocervical mass; she came from an endemic area. Imaging revealed a clearly defined cystic lesion; no hepatic or pulmonary involvement was observed. The cyst was surgically removed without any complications. Postoperative albendazole medication was delivered for 4 months, resulting in no adverse hepatic effects and no recurrence during the follow-up period. This case highlights the diagnostic significance of early multimodal imaging (ultrasound and computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging) for evaluating atypical masses in the neck. Primary cervical hydatid cysts in endemic regions must be considered in the differential diagnosis of cystic neck diseases.

Introduction

The parasitic infection known as hydatid cyst is mostly brought on by Echinococcus granulosus [1]. The liver and lungs are the most common locations for cysts. It is extremely rare for it to occur in the head and neck region [2]. In 20%–30% of instances, more than one organ is implicated, and the liver is always involved [3]. Hydatid disease is endemic in the Middle East, India, Africa, South America, New Zealand, Australia, Turkey, and southern Europe. Due to the increase in emigration and trade, it might also happen in nonendemic countries [4]. While domestic and wild canids are definitive hosts, humans are accidental intermediate hosts [5]. We describe a rare instance of a 13-year-old girl who had a primary cervical hydatid cyst but neither pulmonary nor hepatic cysts. Additionally, we discuss the clinical characteristics and options for treatment in the context of the case while highlighting the rarity of neck hydatid cysts and the challenges faced in diagnosing this rare site. This case report has been reported in line with the Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) checklist [6].

Case presentation

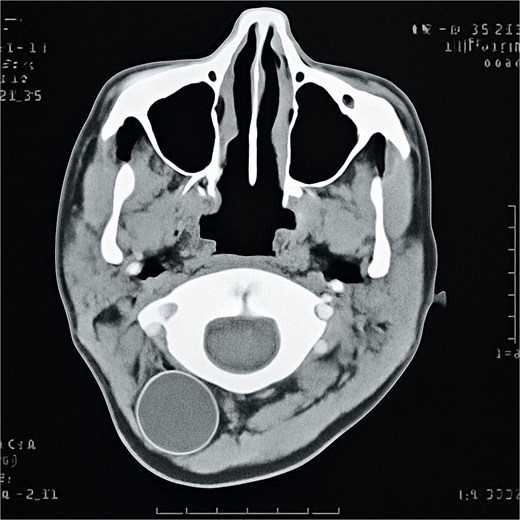

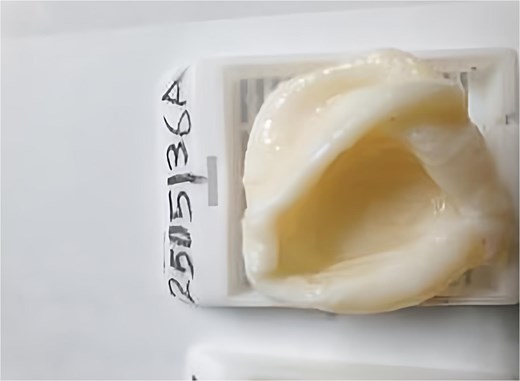

A 13-year-old female patient from the countryside went to the clinic, presenting with an occipitocervical mass. The patient possessed no noteworthy medical history aside from a surgical history of appendectomy. A physical examination indicated a tender and painless occipitocervical mass. Ultrasound identified a 21 × 34 mm fluid-filled cyst. Computed tomography (CT) excluded connection with the meninges or spinal column (Fig. 1). Serologic tests were negative. No additional cysts were identified elsewhere in the body. All laboratory values were within normal limits. The preliminary differential diagnosis included a thyroid cyst, primary thyroid lymphoma, or lymphatic malformations. The patient underwent surgical excision of the cyst without complications and was sent to pathology. Histopathology showed a laminated membrane and inner germinal layer with daughter cysts, consistent with E. granulosus cyst (Figs 2 and 3). Albendazole was administered postoperatively at 400 mg twice daily for 4 months. Throughout this period, liver function tests were monitored biweekly, with results remaining within normal limits. During the follow-up period, there was no recurrence or new cyst formation.

Histopathological image shows daughter cysts in the hydatid cyst.

Discussion

Hydatid disease is a parasitic infection caused by E. granulosus [7]. Hydatid disease is endemic in the Middle East, Africa, India, South America, Australia, New Zealand, Turkey, and southern Europe. It can also occur in nonendemic countries [8, 9]. Humans serve as accidental intermediate hosts, whereas the definitive hosts are wild and domestic canids [7, 8]. Cysts most frequently occur in the liver, lungs, or both (80%–90%) [9, 10]. In our case, the cyst was located in the cervical region, an uncommon site for hydatid disease. Thus, especially in endemic areas, hydatid disease should be taken into consideration when determining a differential diagnosis for cystic cervical masses [5, 11]. In their early stages, hydatid cysts are often asymptomatic and can develop for years without exhibiting any symptoms [9, 10]. The symptoms are frequently determined by the cyst’s size and anatomical location [9]. Cervical infestation symptoms might be mistaken for those of other neck tumors that present with dysphagia, painless or tender swelling, or airway compression [6, 7]. In our case, the patient only presented with a painful occipitocervical mass without any signs of systemic infection or immunological reaction. Medical imaging and laboratory tests are essential for diagnosing hydatid cysts. Ultrasound (US), CT, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the main imaging modalities used for diagnosing hydatid cyst in this region and other body sites [12]. Serological tests have a high sensitivity for the cysts, making them helpful in diagnosis. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is contraindicated in hydatid cysts due to the risk of rupture and anaphylactic shock [13, 14]. Early combined surgical and antiparasitic therapy remains the cornerstone for treatment and to prevent complications and recurrence [12]. In addition to clinical therapy, public health programs such as awareness campaigns, hygiene promotion, and the control of dog and livestock reservoirs are crucial in endemic areas. Similar hydatid cyst cases are extremely rare in the medical literature, such as a 20-year-old male who presented to Hamad Corporation in Doha with a painless neck mass, and the cyst was surgically removed with a good outcome [8]. In our case, physical examination revealed a tender, painful mass, which posed additional diagnostic challenges due to its atypical location and absence of hepatic or pulmonary involvement—i.e. sites usually associated with hydatid disease. As diagnosing hydatid cysts can be hard, we highlight the importance of using early medical imaging to avoid unnecessary interventions and misdiagnosis. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for hydatid cysts in atypical neck masses, particularly in endemic areas. The optimal approach for treatment and prevention of complications and recurrence is a combination of medical therapy with albendazole and surgical excision. Given the diagnostic complexity in such atypical presentations, we highlight the importance of using early medical imaging to avoid inappropriate interventions and misdiagnosis. From a public health standpoint, recognizing such uncommon manifestations may facilitate earlier diagnosis and action, particularly in endemic regions. Hydatid cysts are rare, especially beyond the hepatic and pulmonary areas. This instance underscores the need to include hydatid cysts in the differential diagnosis of neck masses.

Acknowledgement

This work was conducted under the guidance and framework of the Scientific Researchers (SRs) Organization, and we are grateful for their contribution to the coordination and resources that helped make this study possible. (Based in Damascus, Syria. Contact: srsteamsy1@gmail.com)

Author contributions

Mohammad Sibai: Writing original draft. Mais Alreem Basel Mohaisen: Writing, review & editing. Hammoud Hamid, Muataz Aasi, Ahmad Yousef, Mohammed Alarsan, Muhammad Ghanem: Investigation, Reviewing the final manuscript.

M.S. prepared the original manuscript; M.A.B.M. refined, reviewed, and formatted the manuscript. All the authors contributed to reviewing the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images.

Data availability

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Baskaya GHB.

Khazaei S, Rezaeian S, Khazaei Z, et al.

Ahmed EM,