-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Wei Chen, Youfeng Zhou, Chunbo Tang, Xiangcheng Qin, Delayed diagnosis of bladder squamous cell carcinoma secondary to massive bladder stone, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf682, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf682

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 53-year-old man presented to a local hospital for 4 months with lower back discomfort. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a 76 × 74 mm bladder stone. He then underwent bladder incision for stone removal and diversion. Post-surgery, the incision became infected and did not heal. Abdominal CT and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging showed thickened bladder walls and soft tissue in the front of the pelvic area. Pathological examination of abdominal wall tissue biopsy indicated moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. He later received chemotherapy along with immunotherapy. Follow-up CT showed no tumor shrinkage and persistent bleeding. Although rare, bladder squamous cell carcinoma secondary to bladder stones requires awareness to avoid delayed diagnosis and improve early treatment.

Introduction

Urinary system stones are a prevalent group of urinary tract disorders, with bladder stones accounting for ⁓5% of all urinary tract stones [1]. With better living standards and routine check-ups, massive bladder stones are now rare. Bladder squamous cell carcinoma is a relatively uncommon histological subtype among malignant bladder tumors, constituting ⁓2%–3% of all bladder cancers [2]. Such cases are rare and poorly documented. In this report, we present a case of this rare occurrence to urological surgeons. Our aim is to share experiences, raise awareness, enhance diagnostic rates, reduce misdiagnoses, and improve patient outcomes.

Case report

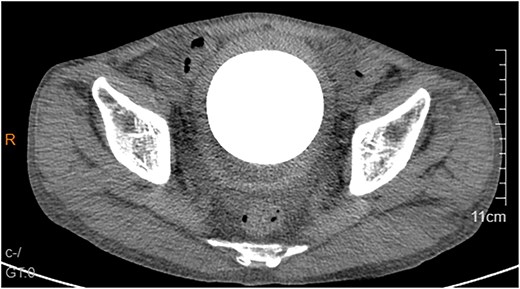

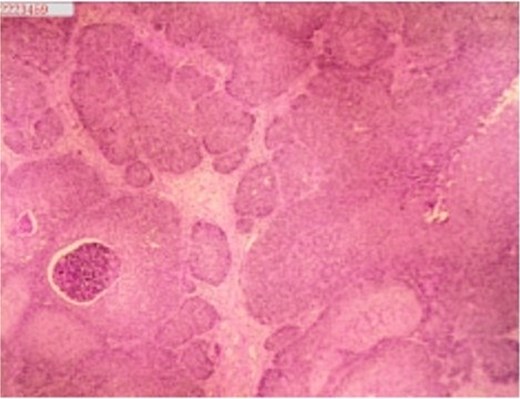

A 53-year-old male, presented to a local hospital in April 2021 due to lower back discomfort. There was no weight loss, fatigue, fever, or other systemic symptoms. Urinalysis showed leukocytes (+++); computed tomography (CT) revealed a 76 × 74 mm stone, bladder wall thickening, and dilation of the bilateral renal pelvis and ureters (Fig. 1). Subsequently, he underwent pubic bladder incision for stone removal and bladder diversion at that hospital. Postoperatively, the incision site was swollen, exuding fluid, and did not heal over an extended period. A total of 14 months after the initial surgery, he was admitted to our hospital. On examination, there was excessive granulation tissue proliferation around the bladder incision wound and near the bladder diversion tube, with surface exudation and easy bleeding upon touch (Fig. 2). Upon admission, urinalysis showed leukocytes (++), occult blood (++), glucose (++), and protein (++). Postprandial blood glucose level was 19.58 mmol/l. Urine culture indicated tropical pseudo-filamentous yeast and Enterococcus. Secretion culture showed E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae subsp. Blood routine test indicated white blood cell count and highly sensitive C-reactive protein within normal ranges. He received infection control, glucose management, and wound care, but the wound did not heal. Abdominal CT and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed bladder wall thickening and soft tissue in the anterior pelvic area (Fig. 3). Histopathological results from abdominal wall tissue biopsy indicated moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry indicated: CK(pan)(+), CK20(−), CK7(−), PAX-8(−), GATA3(−), P63(+), P53(+), Ki-67(+) at 40% (Fig. 4).

Abdominal CT showed a massive bladder stone measuring 76 × 74 mm, thickened bladder walls.

On examination, there was excessive granulation tissue proliferation around the bladder incision wound and near the bladder diversion tube, with surface exudation and easy bleeding on touch.

Abdominal CT and pelvic MRI revealed bladder wall thickening and soft tissue in the anterior pelvic area.

Histopathology of abdominal wall tumor: moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry (10 × 10):CK(pan)(+),CK20(−), CK7(−), PAX-8(−), GATA3(−), P63(+), P53(+), Ki-67(+) at 40%.

A month later, gemcitabine plus cisplatin chemotherapy was initiated, along with concurrent trilpiumab immunotherapy. Follow-up CT after 2 weeks showed no tumor shrinkage. The wound continued to resist healing and recurrent bleeding ensued, leading to severe anemia requiring multiple blood transfusions. Therefore, internal iliac artery embolization was performed. Follow-up abdominal CT indicated no noticeable reduction in the tumor size. Subsequently, two more cycles of gemcitabine plus cisplatin chemotherapy and one cycle of trilpiumab immunotherapy were administered. Nevertheless, the tumor exhibited no apparent changes, with persistent bleeding and necrosis. The patient chose to discontinue further treatment and passed away 3 months after discharge.

Discussion

Bladder stones typically occur under conditions such as bladder outlet obstruction, pelvic surgery, neuro-genic bladder, or the presence of foreign objects within the bladder [3]. In adults without risk factors, spontaneous occurrence of bladder stones in adults is rare. Massive bladder stones are generally defined as those exceeding 100 g in weight or 4 cm in diameter [4, 5]. In this case, the patient reported a history of symptoms including urinary frequency, hematuria, and interrupted urination, persisting for several years, but he did not seek care until bilateral renal dilation and lower back discomfort. This delay in seeking treatment could be attributed to the patient's prolonged single status and lack of family support. Bladder squamous cell carcinoma can be categorized into non-schistosomiasis-associated and schistosomiasis-associated types [5, 6]. In schistosomiasis-endemic areas, it accounts for ⁓59% of bladder cancers [7]. Non-schistosomiasis-associated bladder squamous cell carcinoma is associated with conditions causing chronic bladder irritation. These include bladder stones, recurrent urinary tract infections, chronic bladder outlet obstruction, indwelling catheters, exposure to cyclophosphamide, and even intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin injection. These conditions can lead to frequent regenerative changes and malignant transformation of the bladder epithelium [6, 8]. Reports by Wahyudi et al. described the occurrence of bladder squamous cell carcinoma invading the muscle layer due to a bladder stone measuring ⁓14 × 9 cm, suggesting that chronic mucosal damage caused by bladder stones contributes to the development of bladder squamous cell carcinoma [2]. Cho et al. documented a case of a 76-year-old Caucasian female wit-Mh hematuria and urinary difficulty. Cystoscopy revealed diffuse thickening of the bladder wall with numerous bladder stones, bladder masses, and blood clots. Histopathology of the mass biopsy indicated a high-grade carcinoma with squamous differentiation [3]. Some studies also indicate a positive correlation between bladder cancer risk and kidney or ureteral stones [9–11]. Bladder squamous carcinoma is aggressive, often diagnosed at advanced stages [12]. The majority are of high histological grade [13]. Ploeg et al. found 87.8% of cases had muscle invasion [14]. Kassouf et al. reported that ⁓10% of newly diagnosed bladder squamous cell carcinoma patients already had metastasis. The 5-year and 2-year overall survival rates for non-schistosomiasis-associated bladder squamous cell carcinoma were 10.6% and 47.6% [15].

We believe that for massive bladder stones, a high degree of vigilance towards potential secondary bladder squamous cell carcinoma is necessary. After removing the bladder stone, bladder should be examined during surgery to avoid missed tumors. Patients without obvious tumors should undergo multi-point biopsy of the bladder mucosa, especially those with preoperative imaging suggesting bladder mucosal thickening. For cases where the incision from bladder stone removal surgery does not heal promptly, the possibility of bladder squamous cell carcinoma should be considered as a priority, and timely comprehensive tissue biopsy should be conducted.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

None declared.

Ethical statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient and this study followed the Declaration of Helsinki.

References

- hemorrhage

- biopsy

- squamous cell carcinoma

- urinary bladder calculi

- surgical procedures, operative

- urinary bladder

- neoplasms

- pelvis

- surgery specialty

- abdominal wall

- squamous cell carcinoma of bladder

- lower back

- abdominal ct

- magnetic resonance imaging of pelvis

- delayed diagnosis

- soft tissue

- diversion procedure