-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Jessica A Nicholson, Andrew G Nicholson, Mahmoud K Abd-El-Hafez, Pankti Shah, Mark J Lieser, John M Chipko, Trauma Whipple at a community level 1 trauma center: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf657, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf657

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The Whipple operation is oftentimes considered one of the most challenging and complex abdominal operations, usually reserved for duodenal and hepatopancreatobiliary malignancies. In cases of duodenal and/or pancreatic trauma with disruption of the biliary systems, a Whipple reconstruction can be performed. Such operative traumas are rare and carry with them a high level of morbidity and mortality. This case report presents a challenging 46-day clinical course of a 22-year-old African American female, who suffered multiple gunshot wounds, resulting in severe abdominal injuries. These injuries included a grade 3 duodenal injury, grade 4 pancreatic injury, and a grade 4 renal injury. The patient underwent a staged Whipple operation. Postoperative complications included pancreaticojejunostomy leak, feeding tube leak, and mesenteric bleeding, all of which required surgical and interventional radiology management. After a 46-day hospitalization, the patient was discharged to a rehab facility, achieving an impressive recovery 2 years post-surgery.

Introduction

A traumatic pancreaticoduodenectomy, also known as a ‘Trauma Whipple’ procedure, is a rare and complex surgical intervention primarily utilized in severe traumatic injuries to the pancreas, duodenum, and periampullary region [1]. This is in contrast to its elective counterpart, which is predominantly employed for the treatment of hepatopancreatobiliary malignancy. Traumatic injuries to the pancreas and duodenum are relatively uncommon (<5%) but can have devastating consequences [2]. The procedure consists of removal of the gallbladder, distal antrum, duodenum, and the head of the pancreas, followed by a hepatobiliary and GI reconstruction to restore continuity. For an oncologic resection, the mortality rate is 5% when performed by a sub-specialized surgical oncology/hepatobiliary-trained surgeon [3]. In the setting of trauma, the mortality rate at some institutions has been reported to be as high as 31%–50% [4, 5]. In addition, definitive diagnosis of these injuries on imaging alone may be challenging [6]. We present a Trauma Whipple procedure performed on a 22-year-old female, 2 days following multiple gun-shot wound (GSW) to the upper quadrant.

Case report

A 22-year-old African American female presented to a level-one trauma facility following multiple GSW. Patient was intubated in the trauma bay for a Glasgow Coma Score of 3. Secondary survey revealed bullet wounds to the scalp, upper abdomen, and left thigh. Mass transfusion protocol was activated on arrival for hemorrhagic shock and patient was taken emergently for an exploratory laparotomy following appropriate resuscitation.

Intraoperatively, patient was found to have a grade 3 duodenal, grade 4 pancreatic, grade 4 renal, and extensive injuries to the jejunum and ascending colon. A right nephrectomy, right hemicolectomy and multiple jejunal small bowel resections were performed, leaving the patient in discontinuity. Due to ongoing hemodynamic instability, attempts at surgical repair of the transected pancreatic duct was abandoned. The circumferential defect of the duodenum was oversewn and patient was temporarily closed and transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

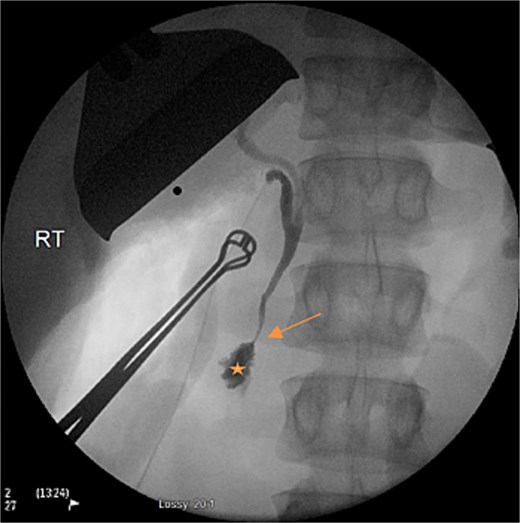

Second-look laparotomy was performed 12-hours following the index operation. A cholecystectomy was performed and jejunal continuity was re-established. Intraoperative cholangiogram was performed (Fig. 1), which showed no contrast flowing into the main pancreatic duct. Drains were placed and the abdomen was again temporarily closed.

Intraoperative cholangiogram on second-look laparotomy demonstrating the lack of filling of the main pancreatic duct (arrow), prior to contrast entering the duodenum (star).

Third-look laparotomy on postoperative day (POD) 2 was performed with the assistance of a hepatobiliary-trained surgeon. The proximal pancreatic duct appeared completely transected and the duodenum was contused, ischemic, and had dehisced its previous repair. The decision was made for a Whipple reconstruction. The duodenum was mobilized and the common bile duct along with the gastroduodenal artery was ligated. The antrum was transected proximally and the duodenum was transected distal to the Ligament of Treitz. The pancreas was divided at its neck following the ligation of the superior/inferior pancreatic arteries. Following the removal of the specimen, a two-layered pancreaticojejunostomy, choledochojejunostomy, and an antecolic gastrojejunostomy anastomosis was created. A jejunal feeding tube was placed via the Witzel technique. Drains were placed, the abdomen was closed, and patient was transferred back to ICU.

On POD 6, refractory hypotension prompted a computed tomography (CT) scan, which showed evidence of obstruction at the J-tube and dehiscence of the pacreaticojejunostomy anastomosis. The abdomen was re-explored, the anastomosis was oversewn, the j-tube was revised, and a decompressive Stamm gastrostomy tube was placed. On POD 11, worsening leukocytosis and distention prompted another re-exploration, which revealed dehiscence of the J-tube enterotomy site, with leakage of enteric content. The site of the j-tube was resected and another j-tube was placed. On POD 20, refractory hypotension prompted another CT, which showed active bleeding along a jejunal branch of the superior mesenteric artery, which prompt embolization by interventional radiology. Patient was discharge to rehab following a 46-day hospital course. On her two-year outpatient follow-up, patient continues to be asymptomatic and without new complaints (Table 1).

Timeline of the surgeries and IR intervention that took place during the hospital admission

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Timeline of the surgeries and IR intervention that took place during the hospital admission

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discussion

Traumatic hepatopancreatobiliary injuries present a challenging scenario in the field of surgery [4]. Treatment of these injuries is guided by their severity, as defined by the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. The scale ranges from grade I (minor injury) to V (complete parenchymal disruption or devascularization) [2]. The decision to perform a Trauma Whipple is controversial, and only justifiable in stable patients with severe combined injuries [7]. This procedure is plagued by intraoperative challenges, including an often-unstable hemodynamics, technical complexities from the blast injuries, and severe intraoperative coagulopathy, acidosis, and hypothermia [7].

Consensus favors damage control laparotomy followed by a staged-pancreaticoduodenectomy, over a one-staged operation. This results in a significant reduction in 30-day mortality, as demonstrated by two single-center studies involving 19 and 15 patients undergoing delayed Whipple reconstruction [5, 9]. The staged-pancreaticoduodenectomy approach prioritizes hemorrhage and contamination control, rather than establishing visceral continuity [4, 8]. This also facilitates the gathering of the proper personal and resources needed for the operation.

The traumatic pancreaticoduodenectomy should be reserved for stable patients presenting with grade 5 pancreatic/duodenal injuries [5]. This cautious approach is necessitated by the tarnished reputation of emergency pancreaticoduodenectomy, due to high morbidity/mortality rates reported in the literature. Krige et al. conducted an analysis of 61 publications, covering a total of 220 cases of traumatic pancreaticoduodenectomy, and discovered an overall mortality rate of 34% [5]. In a review of the National Trauma Data Bank's register for pancreaticoduodenal injuries between 2008 and 2010, it was found that 13 out of 39 patients (33%), who underwent a Trauma Whipple, succumbed to their injuries [10]. There are only a few published series treating more than ten patients with traumatic pancreatoduodenectomy [5].

The role of total pancreatectomy in the trauma setting is limited and considered a last resort when other reconstituting procedures are unfeasible (i.e. Trauma Whipple, lateral pancreaticojejunostomy). This limitation is secondary to the resulting severe and often chronic endocrine/exocrine insufficiency, not reliably ameliorated by islet autotransplantation.

While pre-hospital care advancements, balanced resuscitation, and damage control surgery have significantly reduced trauma-related deaths from hemorrhage over the past decade, the adoption of traumatic pancreaticoduodenectomy among trauma surgeons has remained limited. This reluctance stems from concerns over morbidity rates, with several studies reporting rates as high as 50% to 80% [11, 12]. Postoperatively, our patient's complications (pancreaticojejunostomy leak, mesenteric bleeding, J-tube leak) were managed with interventions. Other potential complications following a Trauma Whipple include pancreatic fistula, pancreatitis, pseudocyst, intra-abdominal abscesses, enterocutaneous fistulas, wound infections, ventral hernias, and ICU-related medical complications [11, 12].

Acknowledgements

There are no personal financial disclosures, non-financial support, or conflict of interest to be acknowledged during the making of this case report. This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities. No external funding was obtained for the completion of this case report.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.