-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Mohanad Ibrahim, Ammar Aleter, Ali Toffaha, Hamza A Abdul-Hafez, Mohammed Yousif, Mohamed Kurer, Desmoid tumor causing large bowel obstruction: an extremely rare diagnosis with an innovative treatment approach, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf644, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf644

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Desmoid tumors are rare, benign, slow-growing, fibroblastic neoplasms that originate from musculoaponeurotic structures throughout the body. Desmoid tumors originating from the abdominal wall or retroperitoneum are extraintestinal lesions that can rarely infiltrate the small bowel or stomach, let alone compress the colon, which is an extraordinary incident leading to mechanical bowel obstruction. Here, we present a rare case of large bowel obstruction caused by a desmoid tumor originating mostly from the abdominal wall that invaded the splenic flexure and stomach in a patient with no history of familial adenomatous polyposis or prior surgical procedures. The extracolonic compression causing obstruction was treated initially with colonic stenting. Such a method of treatment is infrequent with extracolonic lesions since the possibility of migration or failure to release the obstruction is significantly high. The obstruction was released successfully followed by surgery.

Introduction

Abdominal wall or intra-abdominal desmoid tumors typically present as slow-growing, painless lesions [1]. Desmoid tumors that are not linked to familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) generally present with well-defined margins and a lower propensity for infiltration. It is associated with FAP, Gardner syndrome, previous surgical interventions, or post-traumatic incidents.

Mesenteric fibromatosis most commonly arises from the mesentery of the small intestine but can also originate from the ileocolic mesentery, gastrocolic ligament, and omentum [2]. Intestinal obstruction is a rare complication of intra-abdominal desmoid tumors, with only twelve cases of small bowel obstruction described in the literature over the past 30 years [3–5]. Only one patient was described to have a large bowel obstruction caused by compression of a desmoid tumor [6, 7].

Here, we report an extremely rare case of a 36-year-old male presented with obstructive abdominal symptoms that caused by desmoid tumor in splenic flexure, which confirmed using imaging and biopsy. Surgical intervention achieved complete resection with negative margins and an uneventful recovery. This is, to our knowledge, the second reported case of colonic obstruction caused by a desmoid tumor.

Case presentation

This is a 36-year-old male patient with no past medical or surgical history who presented with on-and-off central abdominal pain and weight loss for a few months. The patient started to have signs of obstruction, including nausea, vomiting and abdominal distention, during the last three days prior to admission. He denied any history of bleeding per rectum or melena.

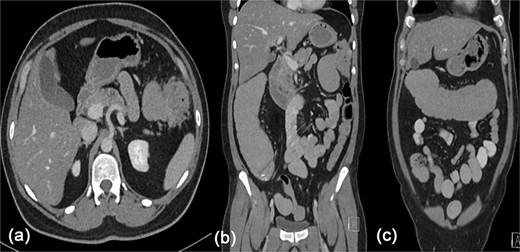

There was significant abdominal distention with mild tenderness during the physical examination, with an unremarkable digital rectal examination. The results of the lab tests were normal, but the computed tomography (CT) scan showed a mass invading the splenic flexure of the colon with an upstream dilation of the transverse colon, ascending colon, and small bowel (Fig. 1).

Contrast enhanced CT scan of the abdomen showing a heterogeneously enhancing lesion at the splenic flexure with upstream dilatation of the transverse and ascending colon.

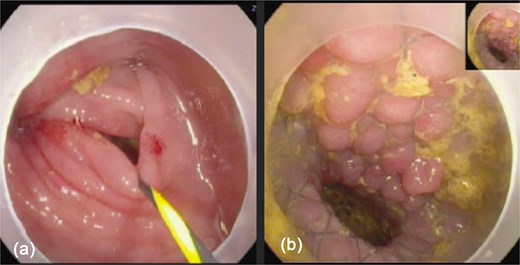

The patient was admitted, and a colonoscopy was done, which showed an area of tight stricture at the splenic flexure with an edematous mucosa. However, no clear mass was identified, denoting the compressing effect of the mass from outside with a clear colonic lumen (Fig. 2). An uncovered stent was deployed across the stricture and the scope was advanced proximally. No mucosal pathology was seen, so no biopsy was taken. Following the stent placement, the patient was able to pass liquid stools and flatus and gradually progressed in diet. As part of the staging work-up, a CT chest was performed, which was negative for metastasis, and tumor markers were also negative. The case was discussed in the gastrointestinal multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. While no distant metastases were detected, the images suggested that the lesion could be invading the greater curvature of the stomach, spleen, and abdominal wall. The MDT decision was to perform Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) and CT-guided biopsy of the lesion followed by resection.

Colonoscopy images: (a) showed tight stricture with normal looking mucosa at the splenic flexure ⁓47 cm from anal verge, (b) shows successfully deployed Niti-S enteral colonic uncovered stent (type D) at the stricture site.

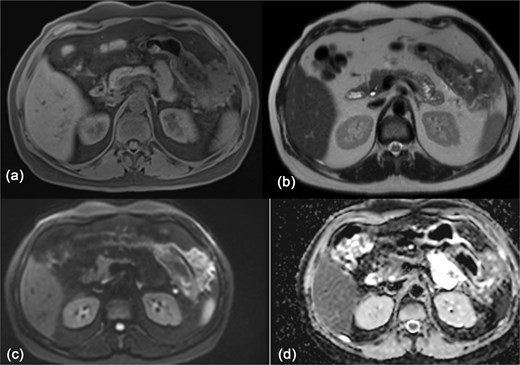

The OGD didn’t show any stomach infiltration or other pathology. CT-guided biopsies were obtained from the mass. Histopathological analysis identified the lesion as a benign fibrous tumor, most consistent with fibromatosis. Further evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an exophytic lesion involving the left lateral abdominal wall with invasion into the splenic flexure and lower pole of the spleen (Fig. 3). The patient was then discharged and scheduled for elective surgery.

MRI of the abdomen showing: (a) T1 weighted image showing isointense exophytic mass at the splenic flexure with close proximity to the abdominal wall and inferior pole of the spleen. (b) T2 weighted image showing heterogeneously hypo-to isointense signal. (c, d) Diffusion weighted images with no diffusion restriction within the mass.

Ten days later, the patient was admitted for elective minimally invasive surgery. Diagnostic laparoscopy revealed a large mass at the splenic flexure that was adherent to the greater curvature of the stomach and anterior abdominal wall. The tumor was not invading the spleen. We proceeded with left hemicolectomy, wedge resection of the stomach and anterior abdominal wall excision.

After complete excision of the tumor, a side-to-side colo-colic anastomosis was achieved. The patient had an uncomplicated post-operative course and was discharged on the seventh postoperative day. The final pathology showed desmoid fibromatosis, involving the abdominal wall, splenic flexure of the colon and gastric wall. All margins are negative. The patient was evaluated in the outpatient clinic, was reassured, and subsequently discharged for regular follow-up.

Discussion

With an incidence of ⁓2–4 cases per million people, desmoid tumors are rare neoplasms that account for 0.03% of all tumors [1]. The term ‘desmoid,’ introduced by Müller in 1838, originates from the Greek word desmos, meaning ‘tendon-like’ [2]. They arise from musculoaponeurotic structures throughout the body, with a predilection for the abdominal wall and intestinal mesentery [3].

Although desmoid tumors lack metastatic potential, they are locally aggressive and frequently infiltrate adjacent tissues, leading to a morbidity rate of ⁓10%. Many patients remain asymptomatic; however, as the tumor enlarges, symptoms may develop due to mass effect and local invasion [6]. In cases of intra-abdominal desmoid tumors, complications such as bowel obstruction and ischemia can occur [8].

Desmoid tumors are typically identified through imaging studies, with CT and MRI being key modalities for assessing the tumor’s extent and its relationship to surrounding structures [4]. MRI is preferred over CT scan for accurately defining the pattern and extent of involvement, particularly before surgical removal [4].

Management of desmoid tumors typically involves a multidisciplinary approach [9]. In an asymptomatic patient, a strategy of close observation is often preferred. However, due to the inevitable progressive growth of desmoid tumors, symptomatic patients typically require surgery with negative surgical margins [7]. Wide local excision with adequate margins has been the mainstay of treatment for over a century, aiming to minimize recurrence and ensure optimal patient outcomes [10]. In 2011, Venkat et al. reported a case of colonic obstruction due to a desmoid tumor, which was treated with a right hemicolectomy [7]. This positions our case as the second documented occurrence in the literature.

In patients presenting with acute left-sided colonic obstruction due to an operable malignancy, self-expanding metallic stent (SEMS) placement facilitates colonic decompression, preoperative bowel preparation, and colonoscopic evaluation for synchronous malignancies [11]. This approach allows for a single-stage surgical procedure instead of creating stoma and multiple-stage surgeries, which may be performed laparoscopically, with primary anastomosis [11].

In our patient, the tumor was extraluminal, evident by the clear colonic lumen. In such cases, stenting is hardly used due to the high possibility of stent migration or stent failure (there is no intraluminal mass for the stent to deploy inside) [12]. Nevertheless, this option was exploited successfully after assessing the tight colonic stenosis caused by the compressing tumor from outside. This is the first described case of colonic obstruction due to an extraluminal desmoid tumor managed by SEMS followed by elective minimally invasive resection [5, 12].

Conclusion

Desmoid tumors are uncommon, with unpredictable clinical behavior. This case represents a unique presentation of large bowel obstruction caused by an extraluminal desmoid tumor. The successful use of an SEMS as a bridging measure for preoperative decompression in this context is both novel and clinically significant, given the uncommon application of stenting in cases of extrinsic colonic compression. This approach enabled a minimally invasive, single-stage resection, avoiding the need for emergency surgery and stoma creation. Our case underscores the importance of multidisciplinary evaluation, individualized treatment planning, and innovative use of endoscopic techniques in managing complex presentations of desmoid tumors.

Author contributions

All authors were contributed to original drafting, literature search, and data conception. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding from an external source.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication and any accompanying images.