-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tarik Deflaoui, Anas Derkaoui, Rihab Amara, Abdelali Guellil, Rachid Jabi, Mohammed Bouziane, Left postpartum diaphragmatic hernia with colonic incarceration: a rare emergency after vaginal delivery, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf630, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf630

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 34-year-old multiparous woman presented three days after spontaneous vaginal delivery with progressive abdominal distension and left-sided dyspnea. Computed tomography imaging revealed an 8 cm left posterolateral diaphragmatic hernia containing the splenic flexure and omentum, associated with upstream bowel dilation and massive ascites. Emergency laparotomy confirmed incarceration of viable colonic and omental structures. After gentle reduction, the defect was repaired using interrupted non-absorbable sutures, and thoracoabdominal drains were placed. The postoperative course was uneventful. This rare case highlights the importance of early imaging and prompt surgical intervention in postpartum diaphragmatic rupture.

Introduction

Spontaneous diaphragmatic rupture in the postpartum period is an exceedingly rare event and is typically associated with sudden increases in intra-abdominal pressure during labor [1]. The left hemidiaphragm is more frequently involved due to its embryological weakness and lack of hepatic protection [2]. Most reported cases follow forceful or prolonged second-stage labor. We report a rare case of postpartum diaphragmatic hernia complicated by colonic incarceration after a non-instrumental vaginal delivery.

Case report

A 34-year-old multiparous woman with no prior surgical or medical history presented three days after spontaneous vaginal delivery with abdominal distension, epigastric pain, and dyspnea. Labor had been unremarkable and without fundal pressure.

On examination, she was hemodynamically stable with tympanic distension and decreased breath sounds on the left. Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis (13 200/mm3), CRP 98 mg/l, and mild anemia (Hb 10.1 g/dl).

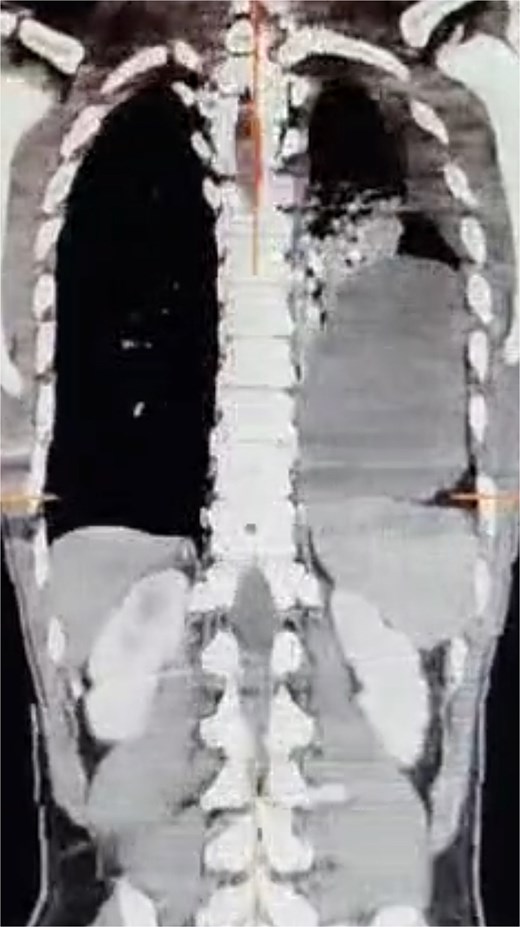

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan revealed an 8 cm posterolateral defect in the left hemidiaphragm with herniation of the splenic flexure and omentum. The herniated bowel appeared viable, with upstream distension and large ascites. A left pleural effusion was also present (Fig. 1).

Contrast-enhanced CT scan showing an 8 cm left posterolateral diaphragmatic defect with herniation of the splenic flexure and omentum into the left thoracic cavity.

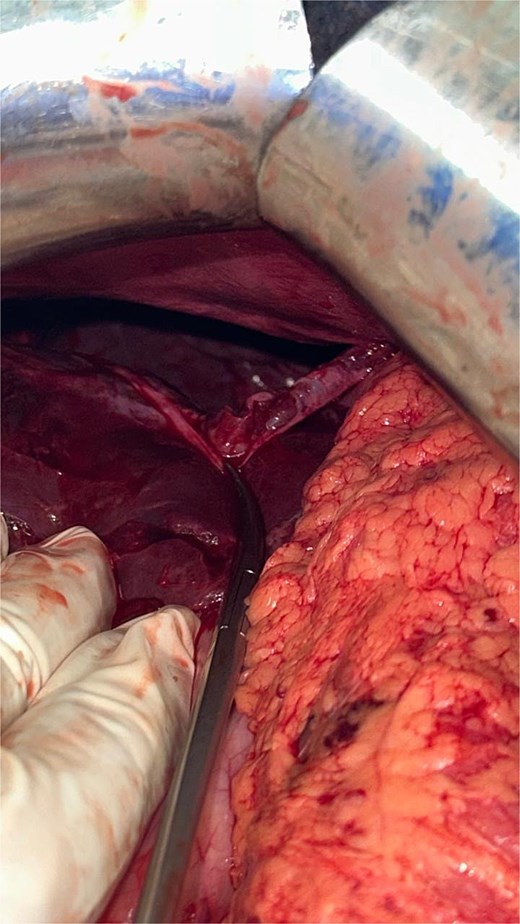

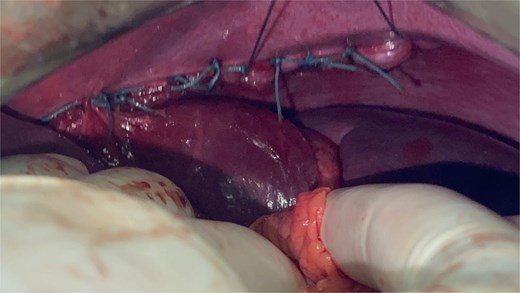

Emergency midline laparotomy confirmed incarceration of the splenic flexure and omentum (Fig. 2). Gentle reduction was achieved. The diaphragmatic defect was repaired with interrupted non-absorbable sutures (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Video 1). Thoracic and abdominal drains were placed. The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged on postoperative day six. At three-month follow-up, CT imaging showed no recurrence.

Intraoperative view showing a full-thickness diaphragmatic rupture at the left posterolateral hemidiaphragm after reduction of the herniated contents.

Surgical repair of the diaphragmatic defect using interrupted non-absorbable sutures.

Discussion

Although rare, diaphragmatic hernias can occur postpartum due to intense intra-abdominal pressure during labor, especially in women with underlying congenital defects such as a Bochdalek hernia [3, 4]. The second stage of labor has been shown to generate pressures exceeding 100 mmHg, sufficient to rupture a weakened diaphragm [5].

Left-sided ruptures are more frequent, as the liver provides natural protection to the right hemidiaphragm, while the left posterolateral area remains vulnerable. The splenic flexure and omentum are commonly involved due to their anatomical proximity and mobility [6, 7].

The clinical presentation is often subtle and misleading, including nonspecific symptoms like abdominal discomfort, nausea, or respiratory difficulty. In the postpartum setting, such symptoms may be misattributed to ileus, constipation, or pulmonary embolism, delaying diagnosis [8]. This highlights the importance of early cross-sectional imaging in postpartum patients with unexplained thoracoabdominal symptoms.

Contrast-enhanced CT is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosis. It allows clear visualization of the diaphragmatic defect, assessment of herniated content viability, and detection of associated complications such as bowel ischemia or ascites [9].

Surgical intervention is always required in symptomatic or incarcerated hernias. In emergency settings, laparotomy is preferred over laparoscopy due to better exposure and control, especially when massive ascites or thoracic involvement is present [10, 11]. The repair of acute ruptures typically involves primary closure with non-absorbable sutures. Mesh reinforcement is reserved for chronic cases or large defects with tissue loss [12].

Postoperative care includes thoracic drainage for re-expansion of compressed lung tissue and close monitoring for abdominal compartment syndrome. Respiratory support, early mobilization, and nutritional optimization play a crucial role in recovery.

Although the literature contains few cases, similar presentations have been reported following vaginal deliveries, sometimes requiring thoracotomy or prosthetic repair [13, 14]. Obstetricians and surgeons should maintain a high index of suspicion in postpartum women with atypical respiratory or digestive complaints, especially multiparas or those with intense expulsive effort.

Limitations

This report is limited by its retrospective, single-patient design, which precludes generalizability or causal inference. While the clinical course was illustrative, the conclusions remain observational. These constraints are inherent to case reports, as outlined by Nissen and Wynn.

Nonetheless, such reports contribute to clinical awareness, especially regarding rare complications of childbirth.

This limitation should be acknowledged as part of any clinical interpretation and educational use of the case [15].

Suggestions for practice include:

Maintaining vigilance for diaphragmatic hernias in the postpartum differential.

Prompt use of thoracoabdominal CT in atypical cases.

Interdisciplinary coordination between obstetricians, radiologists, and surgeons.

Consideration of congenital diaphragmatic anomalies in patients with suggestive symptoms even before labor.

Conclusion

Postpartum diaphragmatic hernia is a rare but life-threatening condition. Prompt diagnosis via imaging and emergency surgical repair are critical. This case illustrates the importance of maintaining clinical suspicion in postpartum patients with nonspecific thoracoabdominal symptoms and underscores the value of rapid multidisciplinary management.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.