-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nihal A Wadid, Rasha A Salama, Hesham A Hamdy, Talaat M Tadross, Hidden in plain sight: diagnostic challenges of gastric trichobezoar in an adolescent—a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf614, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf614

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gastric trichobezoars are rare and often pose a diagnostic challenge due to their nonspecific symptoms and association with underlying psychiatric disorders. In this case, a 14-year-old girl presented with a 3-month history of intermittent abdominal pain, vomiting, early satiety, and a palpable epigastric mass. Although she initially denied any history of trichophagia or trichotillomania, further questioning revealed a year-long habit of hair ingestion that began after an appendectomy. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography imaging confirmed a large gastric trichobezoar extending into the duodenum. Surgical removal of the mass was performed, followed by psychiatric and nutritional counseling. This case highlights the phenomenon of “hidden in plain sight,” where behavioral causes of physical symptoms are initially overlooked. It emphasizes the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for trichobezoars in adolescents with vague gastrointestinal complaints and reinforces the need for a multidisciplinary approach to ensure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and comprehensive follow-up care.

Introduction

Bezoars are concretions of indigestible material that accumulate in the gastrointestinal tract, most commonly within the stomach. Among the various types of bezoars, trichobezoars are formed primarily from ingested hair and represent ~20% of all bezoar cases [1]. In some rare and severe presentations, the hair mass extends from the stomach into the small intestine—a condition known as Rapunzel syndrome [2].

Trichobezoars are strongly associated with trichotillomania, a compulsive disorder characterized by hair pulling, and trichophagia, the compulsive ingestion of hair. These behaviors are classified under body-focused repetitive behavior (BFRB) disorders and are often linked to the obsessive-compulsive spectrum [3, 4]. While the exact etiology remains unclear, these behaviors are believed to be triggered and maintained by psychological stress, trauma, or anxiety, and they may persist due to a reinforcing cycle of temporary emotional relief followed by guilt and concealment [5].

Although bezoars themselves are rare, trichobezoars are particularly uncommon in the pediatric population, occurring in <1% of cases [6], and are predominantly seen in adolescent females [7]. Due to social stigma and embarrassment, many affected individuals conceal their hair-pulling and hair-eating behaviors, delaying diagnosis and intervention [8]. Clinical presentations are typically vague and nonspecific, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, early satiety, and a palpable abdominal mass. Diagnostic tools such as abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy aid in confirming the diagnosis [9].

Management requires not only surgical intervention to remove the mass but also psychiatric support to address the underlying behavioral disorder and prevent recurrence [10]. Here, we present what we believe to be the first reported case in Ras Al Khaimah, UAE, of a trichobezoar in an adolescent girl with associated trichotillomania and trichophagia. The case highlights the diagnostic challenges and the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach.

Case presentation

A 14-year-old girl presented to our emergency department with complaints of intermittent abdominal pain for the past 3 months. The pain had worsened over the preceding 2 weeks and was now associated with repeated episodes of vomiting and early satiety. The patient also noticed a growing mass in her upper abdomen. Initially hesitant to disclose any psychiatric history, she eventually admitted to a habit of eating her hair, which began after undergoing an appendectomy a year prior.

On physical examination, she was alert, afebrile, and vitally stable. Scalp examination revealed diffuse thinning of hair, although no areas of complete alopecia were observed. Abdominal examination revealed a firm, nontender, mobile mass in the epigastric region. Laboratory results were largely unremarkable, although her amylase and lipase levels were mildly elevated.

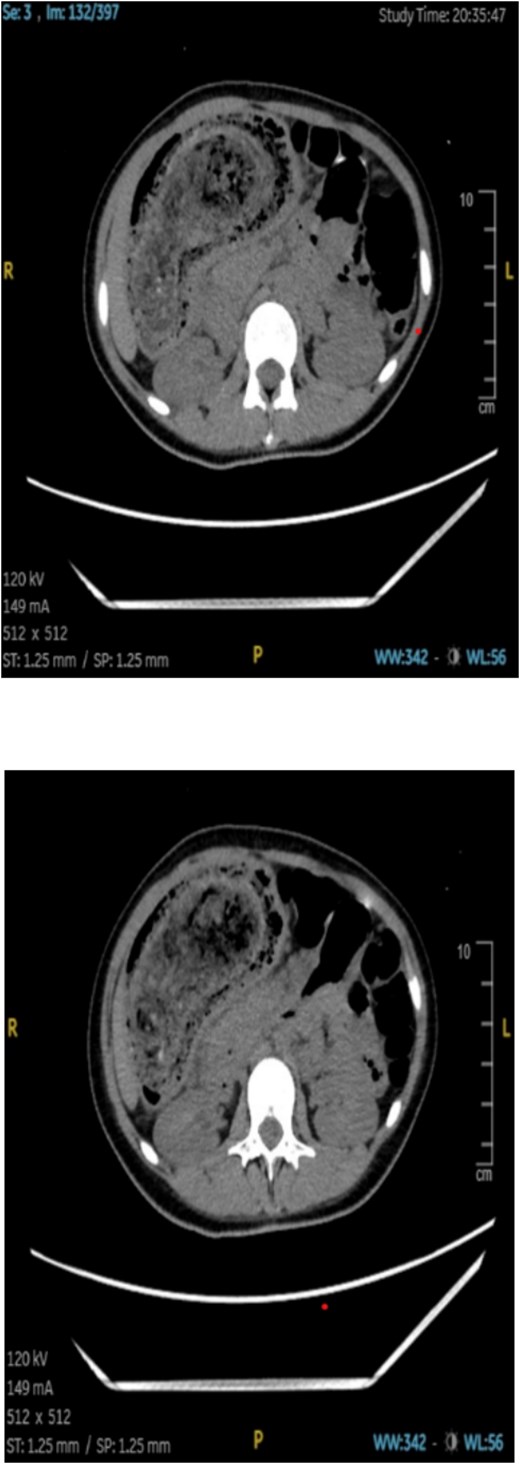

An abdominal CT scan showed a large, intragastric mass with a characteristic mottled appearance and gas entrapment (Figs 1 and 2), consistent with a trichobezoar. The mass extended into the duodenum, confirming the diagnosis of Rapunzel syndrome.

The patient was scheduled for exploratory laparotomy under general anesthesia. Intraoperatively, a large trichobezoar composed of hair and undigested food material was identified and removed via a gastrotomy. The mass measured ~22 × 7 × 8 cm and had a tail extending into the duodenum (Fig. 3). The stomach and intestinal wall were intact, with no evidence of ulceration or perforation. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was started on intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and analgesics. Oral feeding was gradually resumed, and she was discharged in stable condition 5 days after surgery.

During the hospital stay, a psychiatric evaluation was conducted. The patient came from a low-income family and was the eldest of five siblings, two of whom had developmental disabilities. Her mother worked long hours, leaving limited supervision at home. The patient reported persistent urges to pull and eat hair, which she initially engaged in for comfort following her surgery but which later became habitual and distressing. She exhibited signs of emotional dysregulation, moderate depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire – Adolescent version (PHQ-A): 10), anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7): 9), and social withdrawal.

A diagnosis of trichotillomania with trichophagia, along with comorbid depressive and anxiety features, was made. She was started on sertraline 50 mg/day and referred for outpatient cognitive behavioral therapy, focusing on habit reversal training and emotional regulation strategies. Her parents received psychoeducation regarding her condition, its complications, and the importance of ongoing psychiatric care.

Discussion

Trichobezoars typically result from prolonged ingestion of hair, which is resistant to digestion due to its keratin content [11]. Over time, swallowed hair accumulates and entangles with food particles, forming a dense mass within the stomach. Gastric peristalsis fails to expel the mass due to the smooth and slippery nature of hair, allowing it to grow in size [8]. If the mass extends into the small intestine, it is termed Rapunzel syndrome—a rare but more severe presentation.

Studies revealed that most cases are diagnosed in adolescent females, reflecting the higher prevalence of trichotillomania and trichophagia in this demographic [6, 7, 12]. The onset often coincides with psychological stress, trauma, or unmet emotional needs. In our patient, the development of symptoms shortly after an appendectomy and her psychosocial background—including lack of parental supervision, low socioeconomic status, and emotional burden from caregiving—may have contributed to the onset and persistence of her compulsive behaviors.

The clinical presentation of trichobezoar can be subtle or mimic other gasterointestinal (GI) conditions [7, 13]. Early satiety, abdominal mass, and vomiting are common but nonspecific symptoms. In this case, the presence of a palpable epigastric mass and the patient’s eventual disclosure of hair ingestion prompted further imaging, leading to an accurate diagnosis.

CT imaging played a crucial role in the diagnosis; the characteristic “mottled gas” appearance of the mass helped differentiate the trichobezoar from other gastric masses or tumors. Upper GI endoscopy can also be diagnostic and therapeutic in smaller cases, but large bezoars like the one described typically require surgical removal.

Management does not end with surgery. Without addressing the underlying psychiatric disorder, recurrence is likely. Studies suggest that up to 20% of patients may redevelop trichobezoars if psychiatric intervention is not pursued [14, 15]. Our case also highlights barriers to care. The patient and her family were unaware of the psychiatric nature of her symptoms and delayed seeking help due to social stigma. This highlights the need for increased mental health awareness, particularly in adolescents presenting with unusual GI symptoms.

Conclusion

Gastric trichobezoars arising from trichotillomania and trichophagia are uncommon but can cause serious GI complications before psychiatric behaviors are recognized. Prompt diagnosis, via detailed patient history and imaging, and a coordinated treatment plan that includes both surgical removal and mental health intervention are essential to prevent recurrence. This case underscores the need for greater mental health awareness among clinicians and public education to uncover hidden psychiatric contributors to physical illness.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.