-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Hala A Abuhomoud, Tariq A AlTwyjry, Hani AlKhulaiwi, Rema S Almohanna, Small bowel perforation due to toothpick ingestion: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 8, August 2025, rjaf452, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf452

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ingested foreign bodies (FBs) usually pass spontaneously through the gastrointestinal tract without causing complications. However, in ~10%–20% of incidents, the FB fails to pass through the gastrointestinal tract, especially if the object is long or sharp, such as toothpicks. Toothpick ingestion is often associated with significant complications, including obstruction, perforation, and hemorrhage. Herein, we report a case of ileal perforation secondary to accidental toothpick ingestion, which was p initially expected to be a chicken bone. Despite the rarity of toothpick ingestion resulting in intestinal perforation, it is crucial to rule it out as a possible diagnosis when a patient exhibits symptoms of acute abdomen. The aim of this report is to highlight the importance of including toothpick ingestion as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with symptoms of acute abdomen.

Introduction

The ingested foreign body (FB) requiring medical attention is infrequently encountered in the adult population and is most commonly observed in elderly patients wearing dentures, mentally challenged patients, or those related to the ingestion of bones or toothpicks [1]. The majority of cases are reported in pediatric populations, with the incidence peaking at the age of 6 months to 6 years [2].

While in up to 80% of cases FB passes naturally through the gastrointestinal tract, major complications such as bleeding, obstruction, and perforation might occur. Endoscopic intervention is indicated in 20% of cases, and in less than 1% of cases, surgical intervention is warranted [3, 4]. The most common locations for the FB impaction are the rectosigmoid junction and the terminal ileum due to angulation [2, 5]. We present a case of ileal perforation following accidental ingestion of a toothpick.

Case presentation

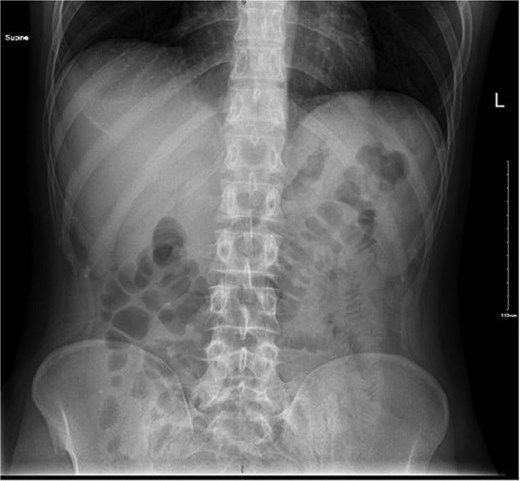

This is a case of a 29-year-old male with no past medical history and a surgical history of open inguinal hernia repair fourteen years ago, who presented to the emergency department complaining of severe abdominal pain for one day. The pain was localized at the lower abdomen, more in the right lower quadrant, and gradually worsened after the patient had eaten his dinner containing poultry. His symptoms were associated with nausea and vomiting, with normal bowel motion. The patient denied fever, hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia. Upon examination, the patient appeared in mild distress due to pain with the following vital signs: temperature: 36.7°C; pulse rate: 96/min; respiratory rate: 19/min; and blood pressure: 138/72 mmHg. The abdominal examination revealed distension, tenderness at the right iliac fossa with signs of muscle guarding and rebound tenderness, and an empty rectum on rectal examination. The laboratory workup results were unremarkable apart from leukocytosis at 13.90 × 109/l. An abdominal X-ray revealed no signs of pneumoperitoneum (Fig. 1).

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed a linear hyperdense structure measuring 3.7 cm in length appearing inside the terminal ileum exiting the lumen medially towards the small bowel loops with no signs of free air, likely representing an ingested bone. There was an edematous wall thickening of the cecum and mucosal hyperenhancement of the appendix, which was likely reactive (Fig. 2).

CT scan showing linear hyperdense structure (arrow) within the terminal ileum perforating medially.

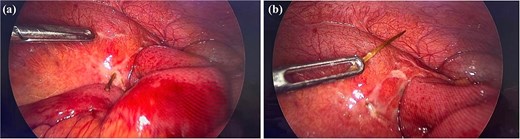

The patient was resuscitated with intravenous fluids, started on ciprofloxacin and metronidazole empirically, and was taken for emergency diagnostic laparoscopy. Intraoperatively, the FB was observed in the distal ileum ~10 cm from the cecum with mild hyperemia, and protruded from the bowel with no other adjacent injuries. It appeared to be a wooden toothpick or similar object (Fig. 3a and b).

Intra operative findings. (a) Demonstrating the toothpick protruding from the ileal wall. (b) The toothpick after extraction.

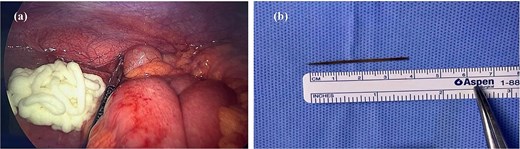

The FB was pulled out of the bowel and the area seemed to be already sealed; thus, a surgifoam was applied at the FB extraction site (Fig. 4a and b).

(a) Demonstrates the surgifoam applied on the previous FB site. (b) The toothpick, measuring 4 cm.

The entire bowel was run after the abdominal cavity was irrigated and suctioned, and no additional obstructions or perforations were found. Upon questioning the patient post-operation, he recalled sleeping with a toothpick in his mouth one day prior to the onset of his symptoms. The patient’s post-operative hospital course was unremarkable, with rapid return of bowel motion on day two, and he was discharged on day three post-operation in stable condition.

Discussion

Toothpick ingestion is considered a medical emergency, necessitating urgent intervention. In a retrospective review of 136 cases of toothpick ingestion, Steinbach et al. reported 79% perforation events with a mortality rate of almost 10% [6]. In the present report, chicken bone was initially suspected to be the cause of perforation. However, after diagnostic laparoscopy and removal of the FB, it was identified to be a wooden toothpick.

The clinical and laboratory data lack specificity, and since wood is radiolucent, imaging studies may not reveal any abnormalities. Toothpicks are frequently missed by standard x-rays or ultrasound scans; however, CT scans provide a more accurate detection method [7].

In a systematic review by Li SF et al. for cases of toothpick ingestion, the definitive diagnosis was made during laparoscopic exploration in up to 53% of the cases, while imaging studies were only helpful in 14% of the patients [8]. Depending on the degree of contamination and the severity of the injury, the treatment strategy may vary from laparoscopic primary repair to intestinal resection.

In the present report, after extraction of the toothpick, the perforation appeared sealed with no apparent contamination, and the site of FB lodgment was managed with a sealant agent. Schwarzova et al. reported a case of toothpick ingestion, which was thought to be a chicken bone initially. During exploratory laparotomy, the FB was identified to be a toothpick, and the pierced bowel was already sealed. No intervention was performed, and the patient was doing well postoperatively and was discharged [9]. Another case reported by Asif et al. showed an ileal perforation secondary to the ingestion of an unnoticed toothpick, which was managed by intestinal resection and anastomosis [7].

As mentioned above, management differs depending on the extent of damage to the bowel, either by resection and anastomosis, primary repair, or, in some cases, no intervention. This report demonstrated the use of a local sealant agent can effectively manage minor perforation, leading to shorter intraoperative duration and less postoperative morbidity.

Conclusion

Ingestion of FB is a challenging diagnosis and a medical history should be taken carefully with physical examination to identify any signs of peritonitis. The appropriate intervention should be tailored according to patients’ stability and overall condition. Different methods can be used depending on the extent of injury, and any delay in intervention increases mortality and morbidity. Although there are very few cases of inadvertent toothpick ingestion resulting in intestinal perforation, ruling out toothpick ingestion as a possible diagnosis when a patient exhibits symptoms of acute abdomen is crucial.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.