-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nikolay Dimov, Evelina Valcheva, Marina Vaysilova, Elizabet Artinyan, Spontaneous steinstrasse—a rare clinical case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 6, June 2025, rjaf455, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf455

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

The term “steinstrasse” was first introduced by Egbert Schmiedt and Christian Chaussy in the 1980s to describe stone accumulation in the ureter following extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Clinically, patients present with lumbar pain, nausea/vomiting, and lower urinary track symptoms. Severe cases may lead to obstruction or sepsis. It is observed mostly in patients who have undergone extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, but in rare cases it can occur spontaneously. Spontaneous formation of steinstrasse is a rare phenomenon with only several cases reported in literature so far and for that reason there are no standard protocols for the management of such patients. Various factors need to be taken into account when choosing the optimal therapeutic strategy. We present a rare clinical case of idiopathic spontaneously occurring steinstrasse. We will discuss the clinical course, the diagnostic algorithm, and the therapeutic approach.

Introduction

Steinstrasse (SS) or “stone street,” represents accumulation of calculi (stones) in the ureter. On radiographic examination, the described changes resemble a cobblestone street, which is where the well-known term, popularized in translation from German, originates [1, 2]. It is observed mostly in patients who have undergone extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) however in rare cases it can occur spontaneously [3, 4]. Information on spontaneous steinstrasse found in literature is scarce. We present a rare clinical case of idiopathic spontaneously occurring steinstrasse.

Case presentation

The patient is a 42-year-old physically active man with a history of nephrolithiasis since childhood. Over the years, he has had multiple episodes of bilateral renal colic and spontaneous elimination of stones. Chemical analysis of these concrements confirmed calcium oxalate composition. The patient has a positive family history for nephrolithiaisis—both his father and grandfather had kidney stones. He had no comorbidities except mild hyperuricemia.

Four years ago, he underwent a single ESWL procedure for a stone in the left ureter. Five months ago, he experienced an episode of right-sided renal colic with evidence of grade 1 hydronephrosis. He underwent conservative treatment with spasmolytics, which relieved his symptoms. Over the next few months, the patient was asymptomatic. During this time, follow-up KUB ultrasound showed several calyceal stones without evidence of hydronephrosis.

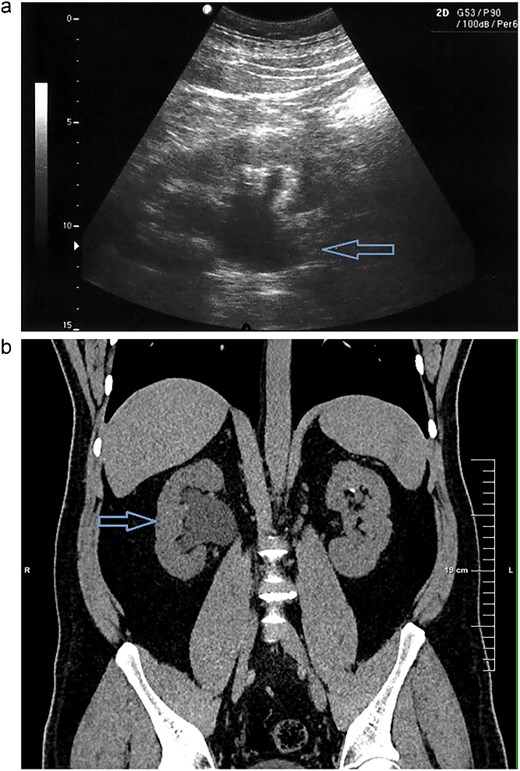

On presentation the patient reported pain in the right lumbar region, without fever starting 1 week prior to admission. The physical examination was unremarkable, except for positive right side Pasternacki's sign. Laboratory tests of full blood count, urinalysis and biochemistry were unremarkable, with the exeption of uric acid that was elevated 483 μmol/L (reference range 208–428 μmol/L) (Tables 1 and 2). Abdominal ultrasound demonstrated grade 2–3 hydronephrosis in the right kidney (Fig. 1a); a 4 mm calyceal stone, without obstruction in the left kidney. Initially, conservative therapy was started. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis revealed bilateral calyceal nephrolithiasis and right-sided ureterohydronephrosis caused by a cluster of stones in the right distal ureter (Figs 1b, 2, and 3).

| Group/Indicator . | Result . | Lower reference limit . | Higher reference limit . | -/H/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC | 5.55 1012/l | 4.5 | 6 | – |

| HGB | 162 g/L | 140 | 180 | – |

| WBC | 9.04 109/l | 3.5 | 10.5 | – |

| PLT | 300 109/l | 140 | 400 | – |

| Creatinine | 106 μmol/L | 74 | 134 | – |

| Urea | 6.9 mmol/L, | 3.2 | 8.2 | – |

| Uric acid | 483 μmol/L | 208 | 428 | H |

| Sodium | 140 mmol/L | 136 | 151 | – |

| Chloride | 104 mmol/L | 96 | 110 | – |

| Calcium | 2.57 mmol/L | 2.12 | 262 | – |

| Potassium | 4.7 mmol/L | 3.5 | 5.6 | – |

| Phosphorus | 1.16 mmol/L | 0.77 | 1.45 | – |

| CRP | 9.5 mg/L | 0 | 10 | – |

| PTH | 47.9 pg/mL | 15 | 67 | – |

| tPSA | 3.24 ng/mL | <4.0 | – | |

| Glucose | 5.3 mmol/L | 2.8 | 6.1 | – |

| AST | 25 U/L | 0 | 50 | – |

| ALT | 28 U/L | 0 | 50 | – |

| GGT | 27 U/L | 0 | 55 | – |

| ALP | 118 U/L | 40 | 120 | – |

| TPROT | 81.1 g/L | 60 | 83 | – |

| Albumin | 47 g/L | 35 | 52 | – |

| ABG: | ||||

| pH | 7.37 | 7.35 | 7.45 | – |

| HCO3 (mmol/l) | 26.5 | 23 | 45 | – |

| BE | −1.5 mmol/L | −2.4 | 2.4 | – |

| PO2 | 85 mmHg | 81 | 100 | – |

| PCO2 | 38 mmHg | 35 | 45 | – |

| Group/Indicator . | Result . | Lower reference limit . | Higher reference limit . | -/H/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC | 5.55 1012/l | 4.5 | 6 | – |

| HGB | 162 g/L | 140 | 180 | – |

| WBC | 9.04 109/l | 3.5 | 10.5 | – |

| PLT | 300 109/l | 140 | 400 | – |

| Creatinine | 106 μmol/L | 74 | 134 | – |

| Urea | 6.9 mmol/L, | 3.2 | 8.2 | – |

| Uric acid | 483 μmol/L | 208 | 428 | H |

| Sodium | 140 mmol/L | 136 | 151 | – |

| Chloride | 104 mmol/L | 96 | 110 | – |

| Calcium | 2.57 mmol/L | 2.12 | 262 | – |

| Potassium | 4.7 mmol/L | 3.5 | 5.6 | – |

| Phosphorus | 1.16 mmol/L | 0.77 | 1.45 | – |

| CRP | 9.5 mg/L | 0 | 10 | – |

| PTH | 47.9 pg/mL | 15 | 67 | – |

| tPSA | 3.24 ng/mL | <4.0 | – | |

| Glucose | 5.3 mmol/L | 2.8 | 6.1 | – |

| AST | 25 U/L | 0 | 50 | – |

| ALT | 28 U/L | 0 | 50 | – |

| GGT | 27 U/L | 0 | 55 | – |

| ALP | 118 U/L | 40 | 120 | – |

| TPROT | 81.1 g/L | 60 | 83 | – |

| Albumin | 47 g/L | 35 | 52 | – |

| ABG: | ||||

| pH | 7.37 | 7.35 | 7.45 | – |

| HCO3 (mmol/l) | 26.5 | 23 | 45 | – |

| BE | −1.5 mmol/L | −2.4 | 2.4 | – |

| PO2 | 85 mmHg | 81 | 100 | – |

| PCO2 | 38 mmHg | 35 | 45 | – |

| Group/Indicator . | Result . | Lower reference limit . | Higher reference limit . | -/H/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC | 5.55 1012/l | 4.5 | 6 | – |

| HGB | 162 g/L | 140 | 180 | – |

| WBC | 9.04 109/l | 3.5 | 10.5 | – |

| PLT | 300 109/l | 140 | 400 | – |

| Creatinine | 106 μmol/L | 74 | 134 | – |

| Urea | 6.9 mmol/L, | 3.2 | 8.2 | – |

| Uric acid | 483 μmol/L | 208 | 428 | H |

| Sodium | 140 mmol/L | 136 | 151 | – |

| Chloride | 104 mmol/L | 96 | 110 | – |

| Calcium | 2.57 mmol/L | 2.12 | 262 | – |

| Potassium | 4.7 mmol/L | 3.5 | 5.6 | – |

| Phosphorus | 1.16 mmol/L | 0.77 | 1.45 | – |

| CRP | 9.5 mg/L | 0 | 10 | – |

| PTH | 47.9 pg/mL | 15 | 67 | – |

| tPSA | 3.24 ng/mL | <4.0 | – | |

| Glucose | 5.3 mmol/L | 2.8 | 6.1 | – |

| AST | 25 U/L | 0 | 50 | – |

| ALT | 28 U/L | 0 | 50 | – |

| GGT | 27 U/L | 0 | 55 | – |

| ALP | 118 U/L | 40 | 120 | – |

| TPROT | 81.1 g/L | 60 | 83 | – |

| Albumin | 47 g/L | 35 | 52 | – |

| ABG: | ||||

| pH | 7.37 | 7.35 | 7.45 | – |

| HCO3 (mmol/l) | 26.5 | 23 | 45 | – |

| BE | −1.5 mmol/L | −2.4 | 2.4 | – |

| PO2 | 85 mmHg | 81 | 100 | – |

| PCO2 | 38 mmHg | 35 | 45 | – |

| Group/Indicator . | Result . | Lower reference limit . | Higher reference limit . | -/H/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC | 5.55 1012/l | 4.5 | 6 | – |

| HGB | 162 g/L | 140 | 180 | – |

| WBC | 9.04 109/l | 3.5 | 10.5 | – |

| PLT | 300 109/l | 140 | 400 | – |

| Creatinine | 106 μmol/L | 74 | 134 | – |

| Urea | 6.9 mmol/L, | 3.2 | 8.2 | – |

| Uric acid | 483 μmol/L | 208 | 428 | H |

| Sodium | 140 mmol/L | 136 | 151 | – |

| Chloride | 104 mmol/L | 96 | 110 | – |

| Calcium | 2.57 mmol/L | 2.12 | 262 | – |

| Potassium | 4.7 mmol/L | 3.5 | 5.6 | – |

| Phosphorus | 1.16 mmol/L | 0.77 | 1.45 | – |

| CRP | 9.5 mg/L | 0 | 10 | – |

| PTH | 47.9 pg/mL | 15 | 67 | – |

| tPSA | 3.24 ng/mL | <4.0 | – | |

| Glucose | 5.3 mmol/L | 2.8 | 6.1 | – |

| AST | 25 U/L | 0 | 50 | – |

| ALT | 28 U/L | 0 | 50 | – |

| GGT | 27 U/L | 0 | 55 | – |

| ALP | 118 U/L | 40 | 120 | – |

| TPROT | 81.1 g/L | 60 | 83 | – |

| Albumin | 47 g/L | 35 | 52 | – |

| ABG: | ||||

| pH | 7.37 | 7.35 | 7.45 | – |

| HCO3 (mmol/l) | 26.5 | 23 | 45 | – |

| BE | −1.5 mmol/L | −2.4 | 2.4 | – |

| PO2 | 85 mmHg | 81 | 100 | – |

| PCO2 | 38 mmHg | 35 | 45 | – |

| Group/Indicator . | Result . | Lower reference limit . | Higher reference limit . | -/H/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine/Specific gravity | 1.010 | 1001 | 1001 | – |

| Urine/pH | 5.50 | 4.5 | 8.0 | – |

| Urine/Protein | Neg /−/ | Neg /−/ | – | |

| Sodium | 140 mmol/L | 136 | 151 | – |

| Urine/Glucose | Neg /−/ | Neg /−/ | – | |

| Urine/Sediment | ||||

| RBC | 2 | 0 | 3 | – |

| WBC | 1 | 0 | 5 | – |

| Electrolites: | ||||

| Potassium | 88.2 mmol/24 h | 25 | 125 | – |

| Sodium | 217 mmol/24 h | 40 | 220 | – |

| Calcium | 5.5 mmol/24 h | 2.5 | 6.2 | – |

| Phosphorus | 11.1 mmol/24 h | 11 | 43 | – |

| Uric acid | 3.61 | 1.48 | 4.46 | – |

| Urine culture | Sterile | |||

| Oxalate | 29 mmol/l | <45.0 | – | |

| Citrate | 469 mg/24 h | 384 | 764 | – |

| Group/Indicator . | Result . | Lower reference limit . | Higher reference limit . | -/H/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine/Specific gravity | 1.010 | 1001 | 1001 | – |

| Urine/pH | 5.50 | 4.5 | 8.0 | – |

| Urine/Protein | Neg /−/ | Neg /−/ | – | |

| Sodium | 140 mmol/L | 136 | 151 | – |

| Urine/Glucose | Neg /−/ | Neg /−/ | – | |

| Urine/Sediment | ||||

| RBC | 2 | 0 | 3 | – |

| WBC | 1 | 0 | 5 | – |

| Electrolites: | ||||

| Potassium | 88.2 mmol/24 h | 25 | 125 | – |

| Sodium | 217 mmol/24 h | 40 | 220 | – |

| Calcium | 5.5 mmol/24 h | 2.5 | 6.2 | – |

| Phosphorus | 11.1 mmol/24 h | 11 | 43 | – |

| Uric acid | 3.61 | 1.48 | 4.46 | – |

| Urine culture | Sterile | |||

| Oxalate | 29 mmol/l | <45.0 | – | |

| Citrate | 469 mg/24 h | 384 | 764 | – |

| Group/Indicator . | Result . | Lower reference limit . | Higher reference limit . | -/H/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine/Specific gravity | 1.010 | 1001 | 1001 | – |

| Urine/pH | 5.50 | 4.5 | 8.0 | – |

| Urine/Protein | Neg /−/ | Neg /−/ | – | |

| Sodium | 140 mmol/L | 136 | 151 | – |

| Urine/Glucose | Neg /−/ | Neg /−/ | – | |

| Urine/Sediment | ||||

| RBC | 2 | 0 | 3 | – |

| WBC | 1 | 0 | 5 | – |

| Electrolites: | ||||

| Potassium | 88.2 mmol/24 h | 25 | 125 | – |

| Sodium | 217 mmol/24 h | 40 | 220 | – |

| Calcium | 5.5 mmol/24 h | 2.5 | 6.2 | – |

| Phosphorus | 11.1 mmol/24 h | 11 | 43 | – |

| Uric acid | 3.61 | 1.48 | 4.46 | – |

| Urine culture | Sterile | |||

| Oxalate | 29 mmol/l | <45.0 | – | |

| Citrate | 469 mg/24 h | 384 | 764 | – |

| Group/Indicator . | Result . | Lower reference limit . | Higher reference limit . | -/H/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urine/Specific gravity | 1.010 | 1001 | 1001 | – |

| Urine/pH | 5.50 | 4.5 | 8.0 | – |

| Urine/Protein | Neg /−/ | Neg /−/ | – | |

| Sodium | 140 mmol/L | 136 | 151 | – |

| Urine/Glucose | Neg /−/ | Neg /−/ | – | |

| Urine/Sediment | ||||

| RBC | 2 | 0 | 3 | – |

| WBC | 1 | 0 | 5 | – |

| Electrolites: | ||||

| Potassium | 88.2 mmol/24 h | 25 | 125 | – |

| Sodium | 217 mmol/24 h | 40 | 220 | – |

| Calcium | 5.5 mmol/24 h | 2.5 | 6.2 | – |

| Phosphorus | 11.1 mmol/24 h | 11 | 43 | – |

| Uric acid | 3.61 | 1.48 | 4.46 | – |

| Urine culture | Sterile | |||

| Oxalate | 29 mmol/l | <45.0 | – | |

| Citrate | 469 mg/24 h | 384 | 764 | – |

(a) Abdominal ultrasound demonstrating right kidney with evidence of grade 2–3 hydronephrosis. (b) Right kidney right-sided ureterohydronephrosis on CT scan.

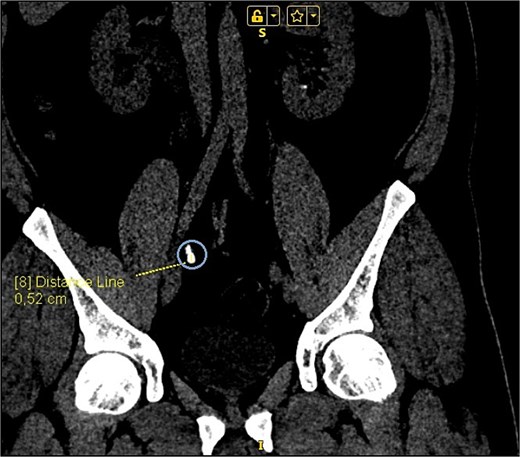

CT scan reconstruction—cluster of stones sizes, respectively, 5.2 mm, 3.2 mm, 2.8 mm—13.4 mm combined in the right distal ureter.

As a result of the CT scan, the diagnosis of spontaneous steinstrasse type 2 with complete obstruction of the right ureter was established. The patient was referred to the urology clinic where a decision was made to perform ESWL. In the following days the patient remained symptomatic with persistent hydronephrosis. Therefore it was decided that the next therapeutic step will be ureteroscopic stone disintegration. The procedure was successful and in the subsequent months, imaging studies showed no signs of hydronephrosis and the patient reported no symptoms.

Discussion

The term “steinstrasse” was first used by Egbert Schmiedt and Christian Chaussy, in the 1980s to denote the accumulation of calculi in the ureter resulting from the performance of ESWL [1]. SS is observed in 15% of patients who have undergone extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy [3]. The classification of steinstrasse includes three types (Table 3) [5]. In our case the patient suffered from type 2 steinstrasse with a leading fragment of 5.2 mm and tail formed by smaller fragments.

| Classification of steinstrasse . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| Type 1 | It is made up of particles 2 mm in diameter or less. |

| Type 2 | It has a leading large fragment of 4–5 mm in diameter with a tail of 2 mm particles. |

| Type 3 | There are multiple fragments in size >5 mm. |

| Classification of steinstrasse . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| Type 1 | It is made up of particles 2 mm in diameter or less. |

| Type 2 | It has a leading large fragment of 4–5 mm in diameter with a tail of 2 mm particles. |

| Type 3 | There are multiple fragments in size >5 mm. |

| Classification of steinstrasse . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| Type 1 | It is made up of particles 2 mm in diameter or less. |

| Type 2 | It has a leading large fragment of 4–5 mm in diameter with a tail of 2 mm particles. |

| Type 3 | There are multiple fragments in size >5 mm. |

| Classification of steinstrasse . | Definition . |

|---|---|

| Type 1 | It is made up of particles 2 mm in diameter or less. |

| Type 2 | It has a leading large fragment of 4–5 mm in diameter with a tail of 2 mm particles. |

| Type 3 | There are multiple fragments in size >5 mm. |

The clinical picture may vary from asymptomatic, more frequently classic renal colic with partial obstruction, and in rare cases, as a complete obstruction. The occurrence of a urinary tract infection (UTI) with urosepsis is possible, as well as a loss of kidney function [3]. The clinical presentation includes pain in the lumbar region, nausea, and vomiting, lower urinary track symptoms. Diagnosis is usually made with the help of various imaging techniques including X-ray, ultrasound and CT, which has the highest informative value [6].

Several cases of spontaneously occurring steinstrasse have been presented in the literature up to date and some of them are related to distal renal tubular acidosis [7, 8]. In our patient arterial blood gas shows no sign of metabolic acidosis, so all forms of renal tubular acidosis (including distal tubular acidosis) were excluded. Other cases demonstrated causative links between idiopathic medullary nephrocalcinosis and steinstrasse [8, 9]. However, our patient has no evidence of hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria, also his parathyroid hormone is within reference range. In our case we have a young male patient with recurrent oxalate urolithiasis, so we had to take Dent disease into account. No proteinuria was detected, urine calcium was within normal range, the patient did not have nephrocalcinosis or impaired renal function, so based on these results we were able to exclude this diagnosis. We registered mildly elevated uric acid in our patient. In general hyperuricemia, may lead to hyperuricosuria, which could lead to formation of uric acid stones, however our patient has proven calcium oxalate calculi and does not have hyperuricosuria, so hyperuricemia is not the main reason for SS in our case. Additionally, we registered normal urine pH and urinary electrolytes without evidence of hyperoxaluria or hypocitraturia. Other major predisposing factors for stone formations were also evaluated—climate, profession [10]. Trough taking detailed patient history we were able to exclude all of the above mentioned factors as a cause of steinstrasse of our case. Via imaging studies, we confirmed the absence of any anatomical abnormalities of the urinary system as well.

Years ago, an ESWL was performed on a calculus in the left ureter, but in this case SS was right-sided. Resultantly, we cannot associate the steinstrasse with the ESWL procedure.

From the detailed metabolic evaluation conducted in our patient, no definite cause for steinstrasse could be identified, and therefore we consider it as idiopathic. Given the patient’s family history, hyperuricemia, and overweight (body mass index 27.5 kg/m2), we suspect that genetic predisposition and diet are probably the contributing factors involved in the development of steinstrasse.

Spontaneous steinstrasse is rare, with only a few cases described in the literature, so no specific treatment recommendations have been developed. In the cases described so far, the approach applied has been similar to that used in post-ESWL steistrasse, so we followed the same principles [3, 6–9].

The current treatment recomendations in post-ESWL includes: conservative, interventional (that includes ESWL, ureteroscopy) and in very rare cases surgical treatment. The optimal therapeutic behavior in each patient is determined depending on the clinical picture, the type according to the well-known classification and the size of the calculi [11].

It is known that 50%–80% of cases of post-ESWL steinstrasse have spontaneous resolution, but in 6% of them, additional interventions are required [12]. In asymptomatic patients or those with mild symptoms, it is permissible to remain on conservative treatment and active follow-up [12]. Conservative treatment is successful in ⁓50% of cases, but only 10% of the patients had steinstrasse type 2 or 3 [6].

If there is no UTI, then ESWL of stone fragments can be done. If steinstrasse is symptomatic and/or there is evidence of UTI, then ureteral stenting or percutaneous nephrostomy placement is advised [13]. In our case the patient was referred for ESWL. Although after the procedure, his symptoms lingered, and the hydronephrosis stayed present. He undergone ureteroscopic stone disintegration as a result.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.