-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

George G Wilson, Kelly Rennie, Case report of a splenectomy secondary to infectious mononucleosis in a 16-year-old female, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 6, June 2025, rjaf420, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf420

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Spontaneous splenic rupture is a rare but life-threatening complication of infectious mononucleosis, occurring in 0.1%–0.5% of cases. We present a 16-year-old female with infectious mononucleosis who developed a spontaneous splenic rupture. Initially managed nonoperatively with distal splenic artery embolization for a grade 3 splenic injury, she later re-presented with worsening abdominal pain. A grade 4 splenic injury with persistent splenic artery flow required an open splenectomy. She was discharged on postoperative day five after drain removal and vaccinations. This case underscores the complexity of managing spontaneous splenic rupture. Although embolization is often effective, failure rates vary, particularly in atraumatic splenic injuries. Early post-embolization imaging and standardized coiling protocols may improve outcomes. Clinicians should remain vigilant for splenic rupture in adolescents with infectious mononucleosis presenting with acute abdominal pain. Further research is needed to assess embolization efficacy in atraumatic splenic injuries.

Introduction

Infectious mononucleosis, commonly caused by the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), is a self-limiting viral illness characterized by fever, tonsillar pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy. EBV during childhood years is often subclinical while the incidence of symptomatic infections tends to rise in adolescence and peaks between 15 to 24 years. An individual infected with EBV can be infectious due to the oral shedding of EBV within 6–18 months after initial infection.

Splenomegaly is present in 50% of patients, with a decrease in size starting at week three. A potentially life-threatening complication of this splenomegaly is spontaneous rupture, which is thought to occur in one to two patients per thousand infected [1]. We present a case of a 16-year-old female with a ruptured spleen secondary to mononucleosis.

Case report

A previously healthy 16-year-old patient presented to her primary care provider with slow onset of fevers, chills, and flu-like symptoms over two weeks, and tonsillar pharyngitis. These symptoms with an unremarkable medical history and up-to-date immunizations resulted in an initial diagnosis of strep throat with a first-line treatment of antibiotics.

After no improvement of symptoms, the patient presented to an urgent care facility where she was diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis, which her symptoms of fevers and myalgias were managed with acetaminophen.

Before admission to our hospital, she felt weak and experienced a near-syncopal event that prompted the first visit to the emergency room (ER) with major complaints of left-sided abdominal pain, left shoulder pain, and fatigue/dizziness.

Findings from her physical examination at the outlying facility stated that her overall appearance was pale with no indications of acute stress, increased heart rate, or body temperature. She had bilateral palpable radial pulses and lungs were clear to auscultation. When examining her abdomen, she exhibited tenderness in the upper left quadrant and a positive Kehr’s sign with no peritonitis.

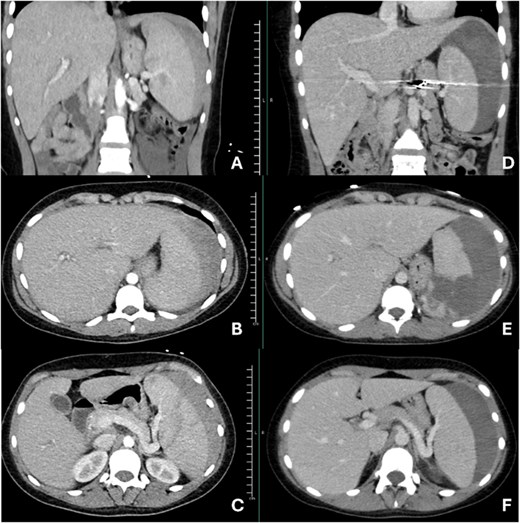

The patient’s complete blood count test revealed a low hemoglobin level and normal white blood cell count. The liver function test reported within a normal range for liver enzymes; however, she tested positive for infectious mononucleosis with a monospot test. The computed tomography (CT) with contrast from outlying facility revealed an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) score of grade 3 splenic injury with hemoperitoneum (Fig. 1A–C). This prompted transfer to the level one trauma center.

Images A, B, and C are representations of initial imaging prior to splenic artery embolization. Images D, E, and F are images taken at her second admission, 12 days after splenic artery embolization. Images D and F show continued flow through the splenic artery.

Upon arrival at the trauma center, vascular surgery deemed her to be appropriate to proceed with a splenic artery embolization with tornado coils. There was minimal flow noted to the superior pole on completion angiogram. She progressed well postoperatively with decreasing pain and was discharged home after her initial hospital course of 3 days.

Unfortunately, she returned to the same outlying facility nine days after discharging due to increasing pain, lethargy, and the inability to tolerate a diet. Workup revealed continued left upper quadrant abdominal pain, a low hemoglobin level, and stable vital signs. She continued to have low-grade fevers thought to be secondary to mononucleosis infection. New CT abdomen/pelvis with IV contrast imaging revealed a significant increase in the patient’s perisplenic hematoma (AAST grade 4 injury) with continued flow through the splenic artery (Fig. 1D–F), which led the surgical team to proceed with an open splenectomy.

At the presurgical consultation, the surgery team discussed the procedure of an open splenectomy with associated procedure complications and obtained parental consent for an open splenectomy. Intraoperatively, the splenic artery and vein were stapled using an Echelon Flex Endopath stapler with a 45 mm white vascular load, followed by silk ties for added security. The short gastric artery branches in the gastrosplenic ligament were ligated with small metallic clips, and a Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain was placed in the upper left quadrant. The patient’s postoperative course was prolonged secondary to pain management. After confirmation that there was no pancreatic fistula, she was discharged on postoperative day 5 after removal of the drain and vaccinations.

Discussion

Splenic rupture is a rare but serious complication of infectious mononucleosis, typically occurring within 0.1%–0.5% of patients during the first 2–3 weeks of illness, with a reported mortality to be 9% [1, 2]. Pathophysiology involves splenic congestion and capsular thinning based on clinical suspicion, imaging findings, and serological confirmation of EBV infection.

The overall failure rate of non-operative management for blunt splenic injury is 3.4%–27%, with increasing rates that correlate with the grade of injury [3]. This rate of failure decreases with the incorporation of splenic artery embolization from 13.3% to 3.1%. This led to treating the patient with a distal coil embolization using tornado coils, which resulted in a completion angiogram showing decreased flow to the spleen with filling to the superior pole. Although the failure rate of splenic artery embolization is 2.7 to 27%, she unfortunately did not receive imaging at the 72-hour postembolization period and presented with a significant worsening of her splenic hematoma [3].

To our knowledge, there is a limited quantity and research on the viability of splenic artery embolization for atraumatic ruptures, given that the pathology is different from trauma. For those cases that have been reported, the mainstay of treatment has been splenectomy [4–6]. Further research is needed to address the gap in knowledge in the management of atraumatic spleen ruptures with splenic artery embolization.

This case report has high educational value in being a novel case of spontaneous splenic rupture in an adolescent patient with infectious mononucleosis, however, it does have limitations based on its retrospective design and limited generalizability. This case report emphasizes that clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for spontaneous splenic rupture in adolescents with infectious mononucleosis with acute abdominal pain. Overall, her case strongly suggests that there should be standardization of coiling techniques and post-embolization imaging. In conclusion, splenic injury and its management continue to evolve with each unique case presentation to improve institutional practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. B.R. and Dr. J.F. for their contributions to this case study.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests and conflicts of interest and all JTACS COI disclosure forms for all authors have been supplied and provided as supplemental digital content.

Funding

No funding was used for the preparation of this case report.

Declaration of consent

Parental consent was obtained for this case report.