-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Nopparuj Sangnoppatham, Natchaya Jitjaturunt, Jitpanu Wongyongsil, Winn Wisawasukmongchol, Panya Thaweepworadej, Peri-renal metastasis of cervical neuroendocrine carcinoma: a case report and literature review, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 6, June 2025, rjaf412, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf412

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix (NECC) is a rare pathological subtype of cervical cancer and patients with NECC usually develop metastasis at the time of diagnosis. While NECC commonly metastasizes to the liver, lungs, and bones, it rarely spreads to renal or peri-renal region. We report a case of a 59-year-old woman with metastatic NECC with peri-renal metastasis. After an en-bloc resection of the kidney, spleen, and distal pancreas, the pathological results suggested metastatic NECC. Further metastatic workup revealed three additional metastases in the bone, mediastinum, and axillary lymph nodes.

Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) account for <2% of all malignancies. Although they most commonly arise in the digestive system, renal NENs are particularly rare due to the absence of intrinsic neuroendocrine cells in normal renal parenchyma [1]. Furthermore, renal metastasis of NENs is extremely rare, with only a few documented cases. Hence, we present our experience of a patient diagnosed with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix (NECC) exhibiting peri-renal metastasis. To achieve curative intent, an en-bloc resection of the kidney, spleen, and distal pancreas was performed.

Case presentation

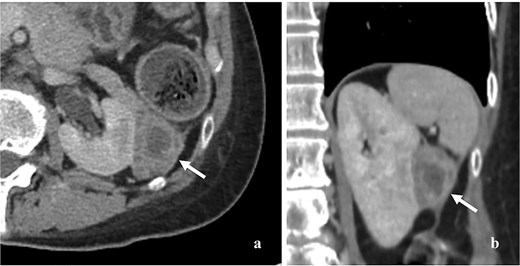

A 59-year-old woman presented with a pancreatic tail mass, incidentally detected during a follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan for colon cancer surveillance. Approximately four years earlier, she had been diagnosed with stage III colon cancer according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) eighth edition. She completed adjuvant chemotherapy, and subsequent surveillance showed no evidence of disease. Three years later, she presented with postmenopausal bleeding. A pathological analysis from fractional curettage confirmed NECC. Further metastatic evaluation, including whole-abdomen and chest CT scans, revealed no evidence of distant organ metastasis. She subsequently underwent concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CCRT) as curative treatment for NECC. During the course of CCRT, after approximately three cycles, the previously mentioned pancreatic tail mass was detected. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the whole abdomen revealed a 4.5 × 4 cm heterogeneous, minimally enhancing mass in the pancreatic tail region with no evidence of pancreatic and renal invasion (Fig. 1). There was no pancreatic duct dilation, lymphadenopathy, or distant organ metastasis. However, the NECC appeared to be responding to CCRT, as the mass had decreased in size compared to previous imaging.

Contrast enhancing CT scan of whole abdomen showed 4.5 × 4 cm heterogeneous and minimal enhancing mass (arrow). (a) Axial section, (b) coronal section.

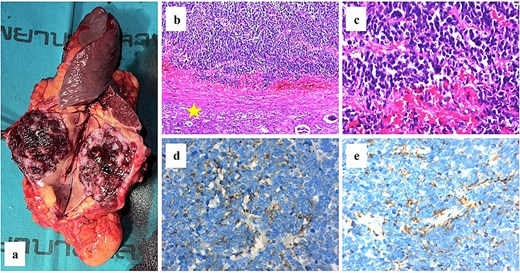

After a multidisciplinary discussion, an en-bloc resection, including distal pancreatectomy, splenectomy, and nephrectomy, was performed. The gross specimen revealed a 5 × 4 cm rubbery mass with a tan to dark brown color. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 7. Histological examination showed atypical small round cells with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, hyperchromatic nuclei, and scant cytoplasm. Notably, the kidney, spleen, and pancreas were not involved by the tumor. Additional immunohistochemical staining was positive for synaptophysin, chromogranin A, CD56, insulinoma-associated protein 1 (INSM-1), and p16 (Fig. 2). The final pathological diagnosis confirmed metastatic NECC. Further metastatic evaluations, including a chest CT scan and bone scan, revealed metastases to the mediastinum, bones, and axillary lymph nodes.

(a) The gross specimen revealed a tan-dark brown rubbery mass measured 5 × 4 cm in size. (b–c) The histological features of hematoxylin and eosin staining were shown and the normal kidney was labeled (star). Immunohistochemical staining results were positive for neuroendocrine markers including chromogranin a (d) and synaptophysin (e).

Unfortunately, approximately one month postoperatively, the patient developed spinal cord compression due to spinal metastasis. She underwent decompressive laminectomy and posterior spinal fixation with tumor removal. Pathological analysis confirmed metastatic NECC. After discussing treatment options with the patient, a palliative care program was selected.

Discussion

NECC is an uncommon pathological subtype of cervical cancer, accounting for approximately 1.4% of all cervical malignancies and carrying a poor prognosis. Compared to squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, NECC has a significantly worse prognosis due to its highly aggressive nature and strong tendency for both lymphatic and hematogenous spreading [2]. While the lungs, liver, and bones are common sites of metastasis for NECC, renal metastases are rarely reported. Even among NENs, only five cases of renal metastasis have been documented to date [3–7]. The clinical features and outcomes of each case are reviewed in Table 1.

Main clinical features of NENs with renal metastasis as reported in literature

| References . | Sex/Age . | Clinical presentations . | Primary tumor . | Primary treatment . | PFS . | Metastatic site(s) (surgical treatment, if any) . | Pathologic finding of kidney . | Subsequent treatment . | Survival outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tal et al. (2003) [3] | F/64 | Neck mass | Lung | Lobectomy | 2 years | Kidney (nephrectomy), liver (wedged excision), neck lymph node (excision) | Carcinoid tumor | NS | NS |

| Kato et al. (2010) [4] | M/56 | Incidental | Rectum | Resection | 8 years | Liver (resection) before Kidney (nephrectomy)a | Carcinoid tumor | NS | NED at 2 years |

| Ali et al. (2015) [5] | F/58 | Incidental | Rectum | Endoscopic treatment | 4 years | Kidney (nephrectomy) | Grade 2 NET | NS | NS |

| Kusuda et al. (2023) [6] | M/66 | Incidental | Rectum | APR | 9 years | Kidney (partial nephrectomy), pancreas, bones | Grade 2 NET | Everolimus | NS |

| Aliyev et al. (2024) [7] | F/41 | Pain in lower extremities | Liver | Somatostatin analog | Synchronous | Kidney (nephrectomy), retroperitoneal lymph nodes, bones | Grade 1 NET | 177 Lutetium-dotatate | NS |

| References . | Sex/Age . | Clinical presentations . | Primary tumor . | Primary treatment . | PFS . | Metastatic site(s) (surgical treatment, if any) . | Pathologic finding of kidney . | Subsequent treatment . | Survival outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tal et al. (2003) [3] | F/64 | Neck mass | Lung | Lobectomy | 2 years | Kidney (nephrectomy), liver (wedged excision), neck lymph node (excision) | Carcinoid tumor | NS | NS |

| Kato et al. (2010) [4] | M/56 | Incidental | Rectum | Resection | 8 years | Liver (resection) before Kidney (nephrectomy)a | Carcinoid tumor | NS | NED at 2 years |

| Ali et al. (2015) [5] | F/58 | Incidental | Rectum | Endoscopic treatment | 4 years | Kidney (nephrectomy) | Grade 2 NET | NS | NS |

| Kusuda et al. (2023) [6] | M/66 | Incidental | Rectum | APR | 9 years | Kidney (partial nephrectomy), pancreas, bones | Grade 2 NET | Everolimus | NS |

| Aliyev et al. (2024) [7] | F/41 | Pain in lower extremities | Liver | Somatostatin analog | Synchronous | Kidney (nephrectomy), retroperitoneal lymph nodes, bones | Grade 1 NET | 177 Lutetium-dotatate | NS |

APR, abdominoperineal resection; F, female; M, male; NED, no evidence of disease; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; NS, not stated; PFS, progression-free survival.

aIn this case, patient developed liver metastasis 2 years after simultaneous resection of rectum and liver. Renal metastasis was identified 8 years after the second liver resection.

Main clinical features of NENs with renal metastasis as reported in literature

| References . | Sex/Age . | Clinical presentations . | Primary tumor . | Primary treatment . | PFS . | Metastatic site(s) (surgical treatment, if any) . | Pathologic finding of kidney . | Subsequent treatment . | Survival outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tal et al. (2003) [3] | F/64 | Neck mass | Lung | Lobectomy | 2 years | Kidney (nephrectomy), liver (wedged excision), neck lymph node (excision) | Carcinoid tumor | NS | NS |

| Kato et al. (2010) [4] | M/56 | Incidental | Rectum | Resection | 8 years | Liver (resection) before Kidney (nephrectomy)a | Carcinoid tumor | NS | NED at 2 years |

| Ali et al. (2015) [5] | F/58 | Incidental | Rectum | Endoscopic treatment | 4 years | Kidney (nephrectomy) | Grade 2 NET | NS | NS |

| Kusuda et al. (2023) [6] | M/66 | Incidental | Rectum | APR | 9 years | Kidney (partial nephrectomy), pancreas, bones | Grade 2 NET | Everolimus | NS |

| Aliyev et al. (2024) [7] | F/41 | Pain in lower extremities | Liver | Somatostatin analog | Synchronous | Kidney (nephrectomy), retroperitoneal lymph nodes, bones | Grade 1 NET | 177 Lutetium-dotatate | NS |

| References . | Sex/Age . | Clinical presentations . | Primary tumor . | Primary treatment . | PFS . | Metastatic site(s) (surgical treatment, if any) . | Pathologic finding of kidney . | Subsequent treatment . | Survival outcome . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tal et al. (2003) [3] | F/64 | Neck mass | Lung | Lobectomy | 2 years | Kidney (nephrectomy), liver (wedged excision), neck lymph node (excision) | Carcinoid tumor | NS | NS |

| Kato et al. (2010) [4] | M/56 | Incidental | Rectum | Resection | 8 years | Liver (resection) before Kidney (nephrectomy)a | Carcinoid tumor | NS | NED at 2 years |

| Ali et al. (2015) [5] | F/58 | Incidental | Rectum | Endoscopic treatment | 4 years | Kidney (nephrectomy) | Grade 2 NET | NS | NS |

| Kusuda et al. (2023) [6] | M/66 | Incidental | Rectum | APR | 9 years | Kidney (partial nephrectomy), pancreas, bones | Grade 2 NET | Everolimus | NS |

| Aliyev et al. (2024) [7] | F/41 | Pain in lower extremities | Liver | Somatostatin analog | Synchronous | Kidney (nephrectomy), retroperitoneal lymph nodes, bones | Grade 1 NET | 177 Lutetium-dotatate | NS |

APR, abdominoperineal resection; F, female; M, male; NED, no evidence of disease; NET, neuroendocrine tumor; NS, not stated; PFS, progression-free survival.

aIn this case, patient developed liver metastasis 2 years after simultaneous resection of rectum and liver. Renal metastasis was identified 8 years after the second liver resection.

In our patient with a complex history of multiple cancer types, the differential diagnosis of the pancreatic tail mass poses a significant diagnostic challenge. Initially, the patient was thought to have an early-stage pancreatic tail tumor. The differential diagnosis for such a lesion includes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), pancreatic NENs, metastatic adenocarcinoma of the colon, and metastatic NECC. Distinguishing between PDAC and pancreatic NENs is particularly crucial, as PDAC accounts for the majority (90%) of pancreatic neoplasms [8]. However, PDAC is typically associated with some degree of ductal obstruction, leading to upstream ductal dilation visible on imaging. In contrast, pancreatic NENs, particularly neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs), are strongly considered in this case as their imaging features often overlap with those of PDAC, except for ductal obstruction [9]. Another potential diagnosis is metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma. However, this is less likely as the pancreas is an uncommon site for colon cancer metastasis [10]. The last possible diagnosis is metastatic NECC which was initially considered less likely. Given that the primary NECC appeared to respond well to CCRT, the development of metastasis would be unexpected. Furthermore, there are no documented reports in the English literature of renal or perirenal metastases originating from NECC.

As pancreatic tail NEC was our primary differential diagnosis, surgery with macroscopic radical intent was recommended [11]. Additionally, for patients with resectable oligometastatic colon cancer confined to a single organ, surgery remains the standard and potentially curative treatment approach [10]. However, the role of metastasectomy in metastatic NECC may be limited [12, 13]. Therefore, an en-bloc resection was performed. When NEC is diagnosed postoperatively, it is important to determine whether it is primary or metastatic. Since p16 immunohistochemistry is used as a surrogate for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection [14] and more than 85% of NECC cases are associated with HPV [13], metastatic NECC is the most reasonable diagnosis in this case. For patients with metastatic NECC, multidisciplinary consultation particularly involving specialized palliative care units should be undertaken to ensure appropriate pain management, psychosocial support, and rehabilitation [12].

Our case also underscores the importance of multimodal approaches and a systematic differential diagnosis. To our knowledge, we are the first to report on peri-renal metastasis of NECC.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr. Panop Limlunjakorn for his expert pathological review.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

Open access funding was provided by Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) General hospital.

Ethics

Ethical approval is exempted for this type of publication in our institution.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.