-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Dhruv Gandhi, Shivangi Tetarbe, Ira Shah, Pradnya Bendre, Gastric duplication cyst or pancreatic pseudocyst: a diagnostic dilemma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 6, June 2025, rjaf373, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf373

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Gastric duplication cysts (GDCs) are rare congenital anomalies that can closely resemble other cystic abdominal lesions, particularly pancreatic pseudocysts. We present the case of a 4-year-old girl with progressive abdominal distension, pain, and elevated serum amylase levels. Initial imaging including an abdominal ultrasound, contrast-enhanced computed tomography, and endoscopic ultrasound, suggested a pancreatic pseudocyst, resulting in an endoscopic cystogastrostomy and stent placement. However, post-procedure magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed a thick-walled cyst with an inner mucosal lining, raising suspicion for a GDC. Surgical excision confirmed the diagnosis, and the patient had an uneventful recovery. This case highlights the diagnostic challenge of differentiating GDCs from pancreatic pseudocysts due to overlapping clinical and imaging features.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal duplications are rare congenital anomalies with a reported incidence of 1:4500 births [1]. They can arise from any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus, with the most common site being the ileum. Gastric duplication cysts (GDC) constitute ⁓2%–9% of all gastrointestinal duplications [2]. Most cases are diagnosed within the first year of life, however, they may present in adulthood as well [3]. GDCs usually present with epigastric pain, vomiting, weight loss, and a palpable abdominal swelling. Several conditions resemble GDCs including hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, duodenal membranes, neurogenic tumors, pancreatic heterotopia, omental cysts, hydatid cysts, other types of duplication cysts, and pancreatic pseudocysts [2, 4, 5]. In particular, pancreatic pseudocysts serve as a close differential due to their common presentation, close location, and similar laboratory and imaging findings [5]. We present a child with high serum amylase levels and an abdominal swelling suggestive of a pancreatic pseudocyst on initial imaging, which was later identified and confirmed as a GDC on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and surgical resection.

Case report

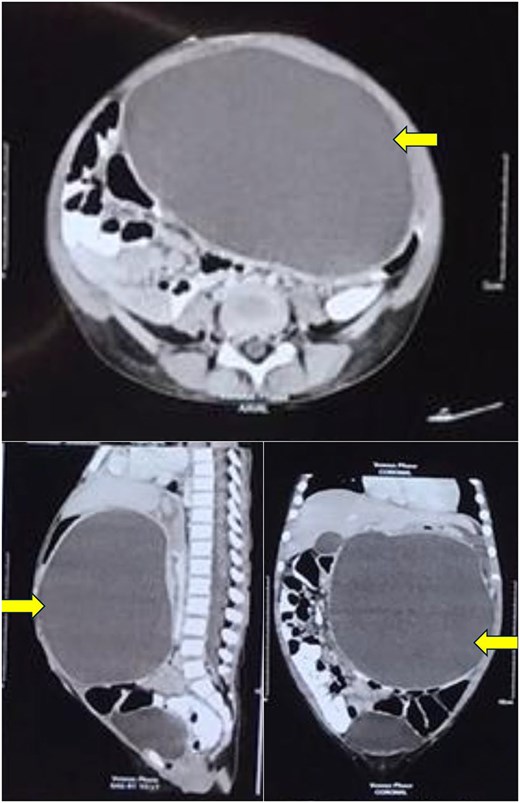

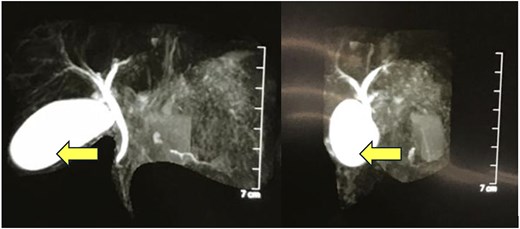

A 4-year-old girl presented in September 2020 with abdominal distention for 1 month and abdominal pain for 20 days. The onset of abdominal pain was associated with repeated episodes of vomiting on a single day. There was no history of abdominal trauma or similar complaints in the past. On examination, an everted umbilicus and distended veins over the abdomen were visualized. The abdomen was tense, distended and a fluid thrill was palpable. Other general and systemic examinations were normal. Serum amylase was 1964 IU/L (normal: 40–140 IU/L). Other investigations of the patient are shown in Table 1. Abdominal ultrasound done prior to presentation in August 2020 showed a well-defined cystic mass in the left lumbar region measuring 10.6 × 12.6 × 12.9 cm (volume: 916 cc) with no septations or solid components within. The wall thickness of the cyst was 6 mm. Contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) of the abdomen showed a large thin-walled cystic hypodense lesion measuring 13 × 10.2 × 17 cm, anterior to the pancreas and compressing and anteriorly displacing the stomach, suggestive of a pancreatic pseudocyst or GDC. The maximum wall thickness was 2.3 mm and there were no calcifications, septations, or solid components within the cyst (Fig. 1). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) showed a large well-defined fluid collection measuring ˃17 cm replacing the entire pancreas, suggestive of a pancreatic pseudocyst. EUS-guided cystogastrostomy was done in which ⁓1.5 L of cyst fluid was aspirated and a double pigtail stent was inserted into the cyst. Post-procedure abdominal ultrasound showed a residual cyst in the epigastric regionmeasuring 9 × 9.5 × 7.5 cm (volume: 360 cc) with the drain in-situ. Post-stenting MRCP confirmed a residual thick-walled cystic lesion with air-fluid levels, anterior to the pancreas and posteroinferior to the stomach, with an inner mucosal lining suggestive of a GDC (Fig. 2). The pancreas appeared normal. She underwent surgical excision which confirmed the diagnosis of a GDC and was doing well on follow-up.

| Parameters . | August 2020 . | September 2020 . | Reference Ranges . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | – | 8.9 | 11.5–15.5 |

| White blood cell count (cells/cumm) | – | 5640 | 5000–13 000 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (cells/cumm) | – | 2482 | 2000–8000 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/cumm) | – | 2425 | 1000–5000 |

| Platelets (105 cells/cumm) | – | 3.17 | 1.50–4.50 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | – | 7 | < 5 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 7 | 19 | <41 |

| AST (IU/L) | 18 | 47 | <41 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 142 | – | 51–332 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 25 | – | 8–38 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0–1.10 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0–0.60 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | – | 8 | 5–18 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | – | 0.24 | 0.3–0.59 |

| Serum total protein (gm/dL) | 7.1 | – | 6.00–8.30 |

| Serum albumin (gm/dL) | 3.4 | – | 3.80–5.40 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | – | 14.8 | 11–14 |

| INR | – | 1.31 | 0.8–1.2 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | – | 138 | 135–145 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | – | 4 | 3.5–5.5 |

| Serum chloride (mEq/L) | – | 104 | 96–106 |

| Serum ionized calcium (mmol/L) | – | 1.17 | 1.16–1.31 |

| Parameters . | August 2020 . | September 2020 . | Reference Ranges . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | – | 8.9 | 11.5–15.5 |

| White blood cell count (cells/cumm) | – | 5640 | 5000–13 000 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (cells/cumm) | – | 2482 | 2000–8000 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/cumm) | – | 2425 | 1000–5000 |

| Platelets (105 cells/cumm) | – | 3.17 | 1.50–4.50 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | – | 7 | < 5 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 7 | 19 | <41 |

| AST (IU/L) | 18 | 47 | <41 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 142 | – | 51–332 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 25 | – | 8–38 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0–1.10 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0–0.60 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | – | 8 | 5–18 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | – | 0.24 | 0.3–0.59 |

| Serum total protein (gm/dL) | 7.1 | – | 6.00–8.30 |

| Serum albumin (gm/dL) | 3.4 | – | 3.80–5.40 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | – | 14.8 | 11–14 |

| INR | – | 1.31 | 0.8–1.2 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | – | 138 | 135–145 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | – | 4 | 3.5–5.5 |

| Serum chloride (mEq/L) | – | 104 | 96–106 |

| Serum ionized calcium (mmol/L) | – | 1.17 | 1.16–1.31 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; INR, international Normalized Ratio.

| Parameters . | August 2020 . | September 2020 . | Reference Ranges . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | – | 8.9 | 11.5–15.5 |

| White blood cell count (cells/cumm) | – | 5640 | 5000–13 000 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (cells/cumm) | – | 2482 | 2000–8000 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/cumm) | – | 2425 | 1000–5000 |

| Platelets (105 cells/cumm) | – | 3.17 | 1.50–4.50 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | – | 7 | < 5 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 7 | 19 | <41 |

| AST (IU/L) | 18 | 47 | <41 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 142 | – | 51–332 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 25 | – | 8–38 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0–1.10 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0–0.60 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | – | 8 | 5–18 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | – | 0.24 | 0.3–0.59 |

| Serum total protein (gm/dL) | 7.1 | – | 6.00–8.30 |

| Serum albumin (gm/dL) | 3.4 | – | 3.80–5.40 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | – | 14.8 | 11–14 |

| INR | – | 1.31 | 0.8–1.2 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | – | 138 | 135–145 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | – | 4 | 3.5–5.5 |

| Serum chloride (mEq/L) | – | 104 | 96–106 |

| Serum ionized calcium (mmol/L) | – | 1.17 | 1.16–1.31 |

| Parameters . | August 2020 . | September 2020 . | Reference Ranges . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | – | 8.9 | 11.5–15.5 |

| White blood cell count (cells/cumm) | – | 5640 | 5000–13 000 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (cells/cumm) | – | 2482 | 2000–8000 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (cells/cumm) | – | 2425 | 1000–5000 |

| Platelets (105 cells/cumm) | – | 3.17 | 1.50–4.50 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | – | 7 | < 5 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 7 | 19 | <41 |

| AST (IU/L) | 18 | 47 | <41 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 142 | – | 51–332 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 25 | – | 8–38 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0–1.10 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0–0.60 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | – | 8 | 5–18 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | – | 0.24 | 0.3–0.59 |

| Serum total protein (gm/dL) | 7.1 | – | 6.00–8.30 |

| Serum albumin (gm/dL) | 3.4 | – | 3.80–5.40 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | – | 14.8 | 11–14 |

| INR | – | 1.31 | 0.8–1.2 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | – | 138 | 135–145 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | – | 4 | 3.5–5.5 |

| Serum chloride (mEq/L) | – | 104 | 96–106 |

| Serum ionized calcium (mmol/L) | – | 1.17 | 1.16–1.31 |

CRP, C-reactive protein; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; INR, international Normalized Ratio.

Computerized tomography of the abdomen showing a large thin-walled cystic hypodense lesion (arrow), anterior to the pancreas and compressing it, anteriorly displacing the stomach and compressing it, and abutting the anterior abdominal wall in axial, sagittal, and coronal views.

MRCP showing a thick-walled cystic lesion (arrow), anterior to the pancreas, postero-inferior to the stomach, extending up to the anterior abdominal wall, with an inner mucosal lining suggestive of a gastric duplication cyst.

Discussion

GDCs are congenital malformations which result from defects in embryonic development. One theory suggests that they result from errors in recanalization and from the fusion of longitudinal folds, leading to the passage of a submucosal and muscle bridge in the second and third months of intrauterine development. Other theories suggest they may result from the traction placed on the endoderm by the notochord as the endoderm elongates at a differential rate or from persistent embryonic diverticula [3]. Thus, GDCs usually present in childhood, with ˂25% presenting in adulthood. On the other hand, pancreatic pseudocysts are rarely congenital and are most commonly acquired following trauma or pancreatitis, however, they may present at any age [6, 7].

Clinical presentation of both lesions are non-specific and variable including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal mass, abdominal tenderness and weight loss [3, 7]. GDCs may present initially with complications including infection, hemorrhage, perforation, ulceration, fistulization, intestinal obstruction, duct compression, and carcinoma within the cyst [3]. Similarly, pancreatic pseudocysts may present with infections, bleeding, cyst rupture, and pancreatic duct disruptions [7]. While a preceding history of acute or chronic pancreatitis is usually seen with pancreatic pseudocysts, ⁓10% of GDCs may have ectopic pancreatic tissue resulting in pancreatitis [3, 7].

GDCs are most commonly located along the greater curvature of the stomach [3]. Pancreatic pseudocysts are commonly located in the lesser sac, near the head or the tail of the pancreas [7]. Due to the proximity of both lesions to the stomach and the pancreas, they are difficult to distinguish pre-operatively [3, 7]. Additionally, GDCs may compress the pancreas and can thus be associated with high serum amylase levels [5]. GDCs share a common contiguous smooth muscle wall with the stomach but they do not communicate with the gastric lumen. GDCs have an inner mucosal lining that may be similar to the gastric epithelium, however, they may also be lined by the epithelium of any part of the alimentary or respiratory tracts [3]. Pancreatic pseudocysts, as the name implies, is not lined by an epithelial layer and has a wall composed of fibrous and granulation tissue [7]. GDCs are classically identified on CECT as a thick-walled cystic lesion indenting the gastric contour with an enhancing inner layer. Calcifications may be occasionally seen as well [3]. However, other than an enhancing inner layer, which may not be demonstrated in every case, pancreatic pseudocysts appear similar to GDCs on CECT [3, 7]. EUS may be useful to distinguish between the two with GDCs showing an echogenic inner mucosal lining surrounded by a hypoechoic intermediate muscle layer, while pancreatic pseudocysts are usually identified as well-defined anechoic lesions within a reflective background [3, 8]. EUS, may also however, fail to distinguish between the two if the GDC is thin-walled and the muscle bundles cannot be identified on EUS [9]. Thus, preoperatively distinguishing GDCs from pancreatic pseudocysts is difficult, and many GDCs may be identified during surgical exploration [5, 9, 10]. Malignant transformation is a known complication of GDCs, with adenocarcinomas being reported in long-standing lesions. The definitive management for GDCs is complete surgical excision to avoid the risk of complications, particularly malignancy [3].

Author contributions

Dhruv Gandhi, Shivangi Tetarbe wrote the initial draft. Ira Shah and Pradnya Bendre edited and critically reviewed the draft. Ira Shah is the guarantor of this paper. All co-authors approved the final draft.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicting interests to declare regarding this manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Consent

Informed patient consent was obtained from the parent of the child.

Guarantor

Ira Shah is the guarantor for this manuscript.