-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Tarik Deflaoui, Anas Derkaoui, Lakhloufi Mohamed, Rihab Amara, Abdelali Guellil, Rachid Jabi, Mohammed Bouziane, Conglomerate of inguinal lymphadenopathies mimicking a strangulated hernia: a case report and review of imaging necessity, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 6, June 2025, rjaf371, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf371

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A strangulated hernia is a common surgical emergency, often diagnosed clinically and managed without preoperative imaging. We report the case of a female patient admitted for a suspected strangulated inguinal hernia. However, intraoperative exploration revealed a conglomerate of inguinal lymphadenopathies, later diagnosed as lymphoma through histopathological analysis. The surgical procedure involved careful dissection and complete excision of the lymphadenopathy mass. This case underscores the critical importance of considering imaging studies, even when clinical presentation strongly suggests a hernia. A diagnostic algorithm is proposed to guide decision-making in similar scenarios.

Introduction

A strangulated hernia is a frequent cause of acute abdomen, particularly in emergency surgical settings. Clinical presentation typically includes a painful, irreducible mass associated with signs of bowel obstruction, prompting urgent intervention to prevent ischemia and necrosis [1, 2]. Given the apparent clarity of such clinical signs, diagnostic imaging is often bypassed [3].

However, inguinal lymphadenopathies—whether infectious, inflammatory, or malignant—can clinically mimic a strangulated hernia [4]. Overlooking alternative diagnoses may lead to inappropriate management and delays in definitive care. This case report aims to highlight the value of preoperative imaging in such scenarios and to propose a structured diagnostic approach to improve outcomes.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with a painful, irreducible mass in the right inguinal region evolving over 24 h. She also reported nausea and vomiting. Clinical examination revealed an erythematous, nonreducible, and tender mass suggestive of a strangulated inguinal hernia.

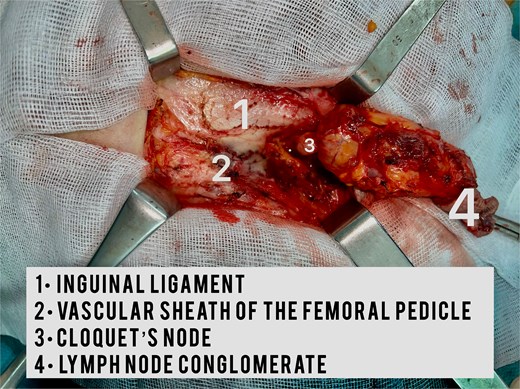

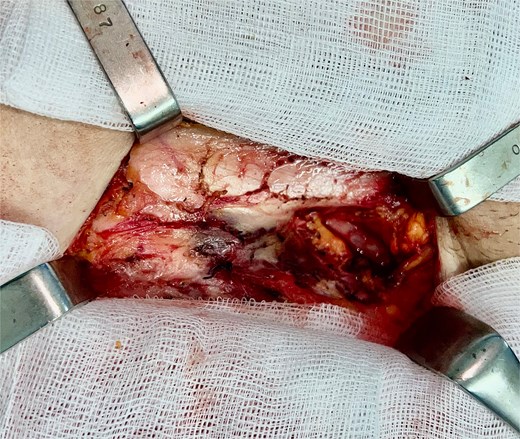

Given the clinical urgency, surgical exploration was performed without prior imaging. Intraoperative findings included a conglomerate of enlarged lymph nodes, with infiltration of the overlying skin. Meticulous subcutaneous dissection was carried out to achieve en bloc resection of the lymph node mass (Fig. 1). The infiltrated skin was excised with the mass to ensure clear margins.

After the identification of a superficial lymph node, its vascular pedicle was carefully ligated prior to excision. Dissection proceeded to Cloquet’s node, allowing for complete en bloc resection of the lymphadenopathy (Fig. 2). Closure of the crural region was achieved using reinforced U-stitches between the inguinal ligament and the pectineal fascia.

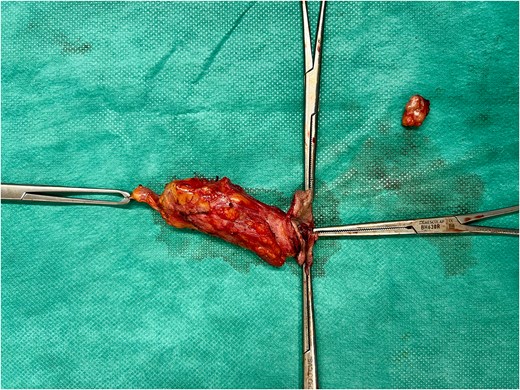

Histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (Fig. 3). The patient was subsequently referred to the oncology department for further management.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis of a painful, irreducible inguinal mass should not be limited to strangulated hernia; other possibilities include lymphadenopathy, soft tissue tumors, and abscesses [5, 6]. Lymphoma presenting as an inguinal mass is well documented and can mimic incarcerated or strangulated hernia due to overlapping clinical features [7, 8].

Inguinal lymphadenopathies can result from infectious, inflammatory, or neoplastic conditions. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, in particular, may present as isolated or clustered nodes in the inguinal region. When inflamed or rapidly growing, these masses can become painful and clinically indistinguishable from hernias [9].

Role of imaging

Ultrasonography, though often sufficient to differentiate hernias from lymphadenopathies, may be limited in complicated presentations. Computed tomography (CT) offers superior diagnostic precision, allowing differentiation between soft tissue masses, hernias, and lymphadenopathy [1, 10].

In emergency situations, hesitancy to perform imaging due to concerns about treatment delay may be counterproductive—especially when clinical findings are atypical. Timely preoperative imaging can improve diagnostic accuracy, facilitate surgical planning, and prevent unnecessary or inappropriate procedures.

Proposed diagnostic algorithm

To improve diagnostic accuracy in patients presenting with suspected strangulated hernia, we recommend the following algorithm:

Clinical examination: Evaluate for classic signs of strangulation (pain, irreducibility, erythema, tenderness).

Rapid bedside ultrasound (if available): Assess for hernia sac contents, vascularity, and other masses.

CT scan (if clinical presentation is atypical or ultrasound findings are inconclusive): Visualize anatomical structures and differentiate between hernia and lymphadenopathy.

Surgical exploration: If imaging is not feasible or if findings strongly suggest strangulation.

Histopathological analysis: Mandatory for all excised tissue to confirm diagnosis.

Conclusion

This case illustrates the diagnostic pitfalls of relying solely on clinical findings to diagnose strangulated hernia. The unexpected intraoperative discovery of lymphoma highlights the necessity of preoperative imaging to avoid misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment. Establishing clear imaging guidelines in emergency scenarios involving suspected hernia is crucial to optimize patient care.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.