-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yuya Kondo, Shingo Tsujinaka, Tomoya Miura, Yoh Kitamura, Yoshihiro Sato, Kentaro Sawada, Atsushi Mitamura, Toru Nakano, Yu Katayose, Chikashi Shibata, Clinical characteristics and surgical management of ileal strictures caused by ischemic enteritis: a report of three cases, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 6, June 2025, rjaf363, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf363

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Ischemic enteritis (IE) is characterized by blood flow insufficient to meet metabolic demands. The incidence of IE is increasing owing to the aging population and advancements in radiographic and endoscopic diagnostics. Many patients eventually require surgical management, indicating an irreversible and progressive pathology. Therefore, clear definitions, early diagnosis, and tailored treatments are crucial. Herein, we report three patients with ileal strictures caused by IE who were successfully treated with surgical resection. In all three cases, the stricture was segmental and located within 50 cm from the ileocecal valve, which is a characteristic radiological feature of IE. Histological analysis revealed segmental, circumferential ulcers with inflammatory-cell infiltration, and fibrosis, although the presentation may vary with the disease phase. Clinicians and surgeons should consider IE in patients with small bowel obstruction and segmental strictures without apparent acute ischemia, especially in older patients with severe comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or thromboembolic diseases.

Introduction

As it has an extensive network of collateral blood vessels, ischemic disease of the small intestine is considered rare [1]. However, older individuals with severe comorbidities may experience intestinal ischemia, which increases the risk of mortality owing to delayed diagnosis [1]. Ischemic enteritis (IE), a condition occurring on a spectrum between abdominal angina and mesenteric infarction, is characterized by blood flow that is insufficient to meet metabolic demands [1–3]. Despite its rarity, an increasing number of diagnoses of IE is being made, likely as a result of advancements in balloon-assisted enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy [3–6]. Many patients eventually require surgical treatment, indicating an irreversible pathology [2, 3, 5–7]. As the global population ages, more IE cases are expected [5], highlighting the need for clear definitions, early diagnosis, and tailored treatments. Herein, we report three cases of ileal strictures caused by IE that required surgical resection and presented with similar clinical characteristics.

Cases

The patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics and surgical and pathological features are summarized in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics, radiographical, and pathological findings of the three cases

| Variable . | Case 1 . | Case 2 . | Case 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 76 | 88 | 82 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male |

| Concomitant diseases | Cerebral infarction, HTN | DM, dyslipidemia, HTN, RA | Angina pectoris (after PCI), DM, HTN |

| History of abdominal surgery | None | Tubal ligation | None |

| Initial symptoms | Abdominal pain | Abdominal pain | Nausea and abdominal pain |

| Initial radiologic features of the intestine | Hepatic portal venous gas without mesenteric ischemia (disappeared after the conservative treatment) | Hepatic portal venous gas and mesenteric emphysema without mesenteric ischemia (disappeared after the conservative treatment) | Enteritis without portal venous gas or mesenteric emphysema |

| Duration of disease before surgery | 142 days | 150 days | 71 days |

| Distal end of bowel stricture from terminal ileum | 50 cm | 30 cm | 30 cm |

| Length of bowel stricture | 10 cm | 8 cm | 12 cm |

| Variable . | Case 1 . | Case 2 . | Case 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 76 | 88 | 82 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male |

| Concomitant diseases | Cerebral infarction, HTN | DM, dyslipidemia, HTN, RA | Angina pectoris (after PCI), DM, HTN |

| History of abdominal surgery | None | Tubal ligation | None |

| Initial symptoms | Abdominal pain | Abdominal pain | Nausea and abdominal pain |

| Initial radiologic features of the intestine | Hepatic portal venous gas without mesenteric ischemia (disappeared after the conservative treatment) | Hepatic portal venous gas and mesenteric emphysema without mesenteric ischemia (disappeared after the conservative treatment) | Enteritis without portal venous gas or mesenteric emphysema |

| Duration of disease before surgery | 142 days | 150 days | 71 days |

| Distal end of bowel stricture from terminal ileum | 50 cm | 30 cm | 30 cm |

| Length of bowel stricture | 10 cm | 8 cm | 12 cm |

DM, diabetes Mellitus; HTN, hypertension; PCI, percutaneous coronary arterial intervention; RA, rheumatoid arthritis

Clinical characteristics, radiographical, and pathological findings of the three cases

| Variable . | Case 1 . | Case 2 . | Case 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 76 | 88 | 82 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male |

| Concomitant diseases | Cerebral infarction, HTN | DM, dyslipidemia, HTN, RA | Angina pectoris (after PCI), DM, HTN |

| History of abdominal surgery | None | Tubal ligation | None |

| Initial symptoms | Abdominal pain | Abdominal pain | Nausea and abdominal pain |

| Initial radiologic features of the intestine | Hepatic portal venous gas without mesenteric ischemia (disappeared after the conservative treatment) | Hepatic portal venous gas and mesenteric emphysema without mesenteric ischemia (disappeared after the conservative treatment) | Enteritis without portal venous gas or mesenteric emphysema |

| Duration of disease before surgery | 142 days | 150 days | 71 days |

| Distal end of bowel stricture from terminal ileum | 50 cm | 30 cm | 30 cm |

| Length of bowel stricture | 10 cm | 8 cm | 12 cm |

| Variable . | Case 1 . | Case 2 . | Case 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 76 | 88 | 82 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male |

| Concomitant diseases | Cerebral infarction, HTN | DM, dyslipidemia, HTN, RA | Angina pectoris (after PCI), DM, HTN |

| History of abdominal surgery | None | Tubal ligation | None |

| Initial symptoms | Abdominal pain | Abdominal pain | Nausea and abdominal pain |

| Initial radiologic features of the intestine | Hepatic portal venous gas without mesenteric ischemia (disappeared after the conservative treatment) | Hepatic portal venous gas and mesenteric emphysema without mesenteric ischemia (disappeared after the conservative treatment) | Enteritis without portal venous gas or mesenteric emphysema |

| Duration of disease before surgery | 142 days | 150 days | 71 days |

| Distal end of bowel stricture from terminal ileum | 50 cm | 30 cm | 30 cm |

| Length of bowel stricture | 10 cm | 8 cm | 12 cm |

DM, diabetes Mellitus; HTN, hypertension; PCI, percutaneous coronary arterial intervention; RA, rheumatoid arthritis

Case 1

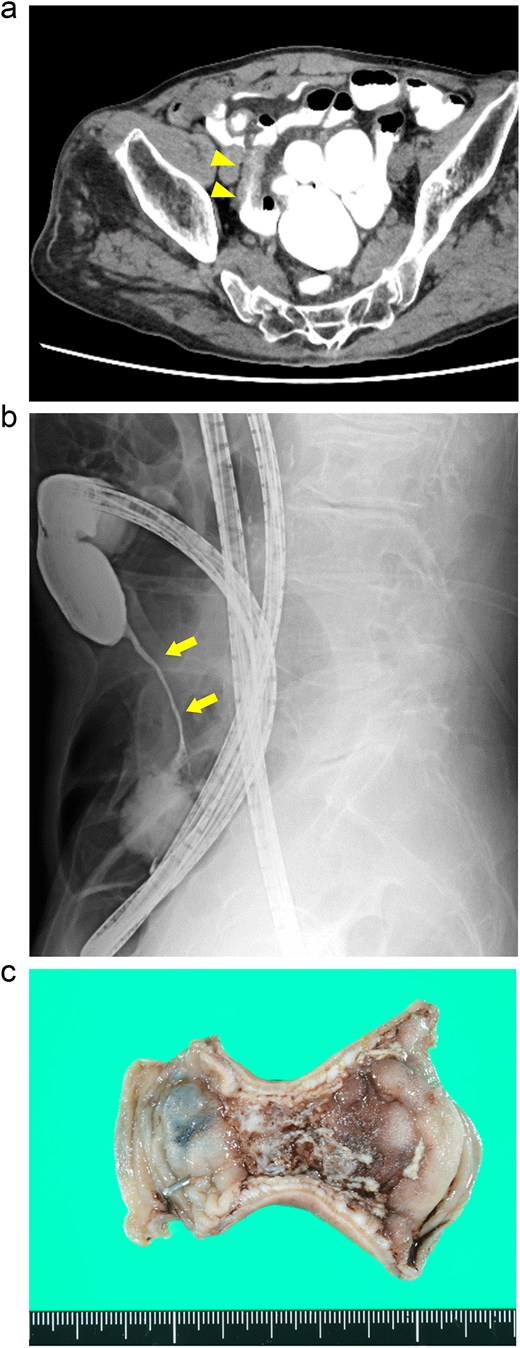

A 76-year-old man presented with a gradual onset of intermittent epigastric and left abdominal pain. Three months prior, he experienced similar pain, and computed tomography (CT) revealed hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) without mesenteric ischemia or bowel strictures. The patient’s symptoms resolved with conservative treatment, none of the CT features during follow-up. His vital signs were stable, and laboratory test results were normal, including a white blood cell (WBC) count of 8800/μl, C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration of 0.02 mg/dl, hemoglobin (Hb) level of 12.5 g/dl, and lactate (Lac) concentration of 0.7 mmol/l. CT enterography revealed a segmental stricture with wall thickening in the distal ileum (Fig. 1a). Double-balloon endoscopy (DBE) revealed a circumferential ulcer and segmental stricture in the distal ileum. Fluoroscopy during DBE confirmed segmental, smooth luminal narrowing in the distal ileum (Fig. 1b).

Case 1: (a) CT enterography with water-soluble contrast agent. The arrowheads indicate a segmental stricture with wall thickening in the distal ileum. (b) Fluoroscopy during double-balloon endoscopy. The arrows indicate a segmental, smooth luminal narrowing in the distal ileum. (c) Macroscopic view of the resected specimen. Circumferential ulceration is visible in the affected area.

Exploratory laparoscopy revealed a 10-cm-long segmental bowel stricture with wall thickening 50 cm from the ileocecal valve, which was resected. The pathological specimen revealed a circumferential ulcer with granulation tissue at the stenotic site, accompanied by edematous mucosa and fibrotic submucosa in the surrounding areas. No signs of tumors or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were noted (Fig. 1c). The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the ninth postoperative day. By the 10-month follow-up, he had not had any recurrences of abdominal symptoms.

Case 2

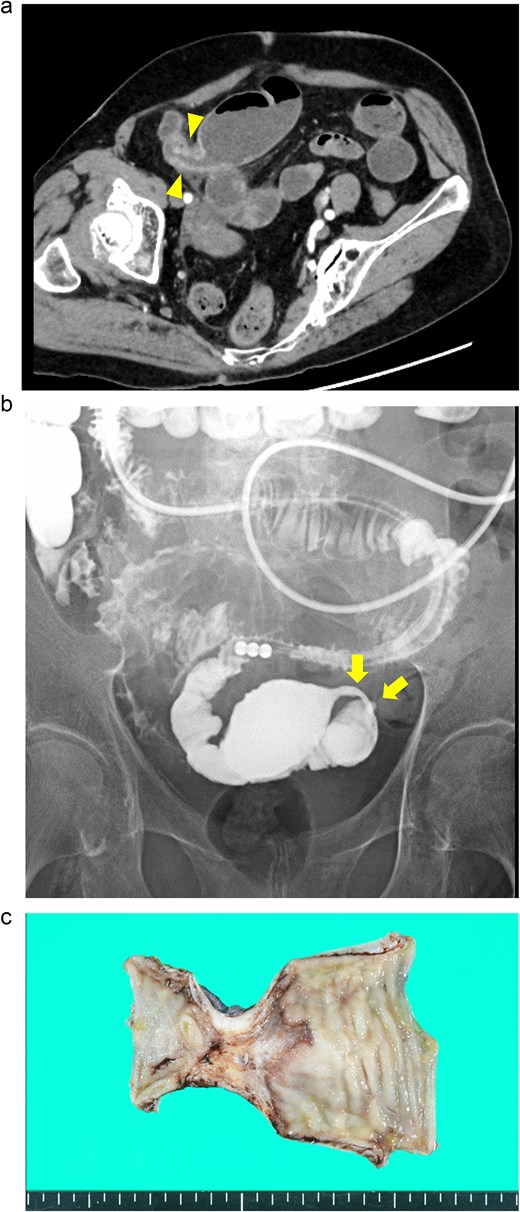

An 88-year-old woman presented with recurrent episodes of epigastric pain. Three months prior, she experienced similar abdominal pain, and CT revealed HPVG and mesenteric emphysema without mesenteric ischemia or bowel strictures. The patient’s symptoms resolved with conservative treatment, and none of the CT features remained by the follow-up. Her vital signs were stable, and most of the laboratory test results were normal, including WBC count (6700/μl), CRP concentration (0.95 mg/dl), Hb level (12.3 g/dl), and Lac concentration (0.9 mmol/L). However, her blood glucose level (BGL) was elevated (315 mg/dl), as was her glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level (9.0%). Contrast-enhanced CT revealed a segmental luminal stricture with wall thickening in the distal ileum, suggestive of bowel obstruction (Fig. 2a). A long intestinal tube was placed for luminal decompression, and fluoroscopy confirmed the presence of segmental, smooth luminal narrowing in the distal ileum (Fig. 2b).

Case 2: (a) Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen. The arrowheads indicate segmental luminal stricture with wall thickening in the distal ileum. (b) Fluoroscopy with a long intestinal tube. The arrows indicate a segmental, smooth luminal narrowing in the distal ileum. (c) Macroscopic view of the resected specimen. Circumferential ulceration and surrounding fibrosis are visible in line with the stenotic site.

Exploratory laparoscopy revealed an 8-cm-long bowel stricture with segmental induration 30 cm from the ileocecal valve, which was resected. The pathological specimen revealed circumferential ulcer formation at the stenotic site, accompanied by granulocyte infiltration and fibrosis extending from the submucosa through the proper muscle layer. No signs of tumors or IBD were noted (Fig. 2c). The postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged on the eighth postoperative day. By the 16-month follow-up, she had not had any recurrences of abdominal symptoms.

Case 3

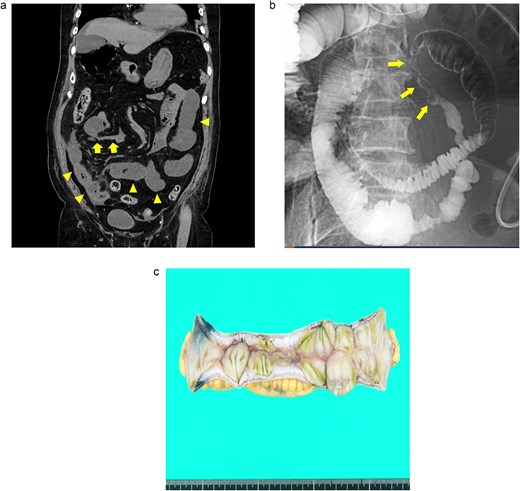

An 82-year-old man presented with recurrent nausea and abdominal pain that had persisted for 3 days. His vital signs were stable, and laboratory test results were as follows: a normal WBC count (3500/μl), elevated CRP concentration (35.4 mg/dl), slight anemia (Hb level:11.7 g/dl), normal Lac concentration (0.8 mmol/L), elevated BGL (259 mg/dl), and elevated HbA1c level (7.3%). Plane CT revealed a segmental stricture without wall thickening in the distal ileum. His proximal small bowel was dilated, and increased attenuation was observed within the adjacent mesenteric fat (Fig. 3a). No HPVG or mesenteric emphysema was observed. The preliminary diagnosis was enteritis without bowel ischemia. The patient was initially tolerant of the conservative treatment and discharged. However, abdominal pain recurred 5 days after discharge, necessitating readmission. Because his symptoms of nausea/vomiting and abdominal pain gradually worsened, a long intestinal tube was placed for luminal decompression. Fluoroscopy revealed segmental, irregular, patchy luminal narrowing of the distal ileum (Fig. 3b). Exploratory laparoscopy revealed a 12-cm-long segmental bowel stricture 30 cm from the ileocecal valve, which was resected. Pathological examination revealed multiple patchy, longitudinal ulcers, and wall thickening at the stenotic site, with granulocyte infiltration and fibrosis extending from the muscularis mucosae through the proper muscle layer. No signs of tumors or IBD were noted (Fig. 3c). The postoperative course was complicated by aspiration pneumonia and transient abdominal pain without intra-abdominal sepsis. He gradually recovered and was transferred to a satellite hospital for continuing care on the 50th postoperative day. The patient’s clinical course at the satellite hospital was uneventful. By 7 months after surgery, he had not had any recurrences of the abdominal symptoms.

Case 3: (a) Plain CT of the abdomen. The arrows indicate a segmental stricture in the distal ileum. The arrowheads indicate dilatation of the small bowel. (b) Fluoroscopy with a long intestinal tube. The arrows indicate segmental, irregular, patchy luminal narrowing of the distal ileum. (c) Macroscopic view of the resected specimen. Multiple longitudinal ulcers with irregular wall thickening are visible in the affected areas.

Discussion

IE is traditionally classified as either transient or stenotic type [2, 3, 6]. The transient type is a non-occlusive condition resulting from mild ischemic changes to the mesentery, with symptoms often resolving spontaneously, although the initial treatment response may be delayed [2, 3, 6]. The stenotic type is an occlusive condition with ischemia spreading from the submucosa to the muscle layers owing to chronic inflammation. Treatment depends on the disease progression: (1) for transient, reversible ischemia, conservative treatment can be indicated; (2) for ischemia progressing to gangrene, immediate surgery may be required if clinical deterioration occurs; and (3) for ischemia progressing to stricture formation, surgery is required if a bowel obstruction develops [2]. Most stenotic cases require surgery, but complete occlusion is rare and may be alleviated by bowel rest [2, 3, 6].

In all three cases in this report, the stricture was segmental and located within 50 cm from the ileocecal valve, consistent with those in previous reports, indicating that ileum is more susceptible to ischemic injury than the jejunum [3, 6, 8]. Several explanations may be proposed. (1) The superior mesenteric artery arises from the abdominal aorta at an oblique angle, causing emboli to lodge distally to the origin of the middle colic artery. Consequently, the distal ileum is more susceptible to arterial embolism than the jejunum [1, 7, 9]. (2) Arterial thrombosis often affects the proximal small intestine, particularly the jejunum, when atherosclerosis occurs near the origin of the superior mesenteric artery [1, 9–11]. (3) The number of arcades is significantly greater in the ileum, and its arteriae recta are more numerous, shorter, and narrower than those in the jejunum [12].

The most frequent cause of acute mesenteric ischemia is arterial embolism, followed by arterial thrombosis, non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI), and mesenteric venous thrombosis [1, 2, 9–11]. Previous studies have revealed that approximately half of patients have underlying diseases, including hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, cerebrovascular disease, and cardiovascular disease [3, 6]. In this report, all three patients had hypertension and either diabetes, dyslipidemia, or thromboembolic disease, suggesting that vascular factors are predominant in the development of IE.

The most common symptom in patients with IE is abdominal pain (67%–94%), followed by nausea/vomiting in stenotic cases (33%–67%) [3, 6]. Variations in symptoms may be associated with the severity and duration of intestinal ischemia [6]. In Cases 1 and 2, the patients presented with repeated or intermittent abdominal pain and were initially managed conservatively, suggesting acute and transient disease phases. However, both patients returned with a relapse of abdominal pain and bowel stricture 4–5 months later, indicating a transition from the transient to the chronic disease phase. Conversely, in Case 3, the patient might have been in the acute-on-chronic disease phase at the time of the initial diagnosis, presenting with progressive abdominal pain and nausea/vomiting owing to an irreversible bowel stricture.

Laboratory tests revealed nonspecific patterns, varying among the three cases, although the slight elevation in CRP concentration observed in Case 3 was also previously reported [3, 6]. The typical endoscopic features are segmental and circumferential ulcers or scarring [1, 3, 6]. Differential diagnoses include small bowel carcinoma, IBDs, intestinal anisakiasis, and Henoch–Schönlein purpura [1–3, 6]. After these pathologies are excluded, endoscopic balloon dilation can be attempted, especially when the stricture is short (<3 cm) [3, 6, 13]. In our study, only one patient underwent DBE, which revealed circumferential and segmental ulcers consistent with IE (Case 1). The remaining two patients did not undergo DBE owing to the placement of a long intestinal tube. All patients were symptomatic, and preoperative fluoroscopy revealed tubular and segmental bowel strictures that were presumably longer than 3 cm. The resected specimens revealed stricture lengths of 8–12 cm, indicating that endoscopic balloon dilation would not have been suitable.

Radiology revealed segmental, tubular, and afferent strictures with a “lead pipe appearance” in Cases 1 and 2, and a segmental, irregular, patchy stricture with the “thumbprinting sign” in Case 3. The lead pipe appearance is a characteristic of IE, whereas the thumbprinting sign may indicate mucosal and submucosal edema, reflecting various disease phases of IE [2, 3, 6]. Abdominal CT generally has poor sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia [9, 11]. However, segmental bowel-wall thickening without decreased enhancement must be identified via contrast-enhanced CT to differentiate IE from other intestinal ischemia pathologies [3]. The presence of dilated, fluid-filled bowel loops may exclude NOMI [3, 11]. The next step is to differentiate among IE-causing intestinal strictures, such as malignant tumors, inflammatory diseases, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced enteritis, and infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis [2, 3, 6, 11].

Interestingly, HPVG was observed during the initial disease phase in patients who developed bowel obstruction at a later stage (Cases 1 and 2). HPVG is associated with various clinical conditions, including bowel necrosis, dilation of the digestive tract, intraperitoneal abscesses or tumors, gastric ulcers, IBD, complications from endoscopic procedures, and suppurative cholangitis [14, 15]. HPVG is linked to both fatal and nonfatal pathologies. A literature review revealed that 46% of patients with HPVG required surgery, whereas 43% were successfully treated conservatively [14]. This suggests that treatment of HPVG should be tailored to the specific underlying conditions [14, 15]. In our cases, transient IE with bowel dilatation led to HPVG at the initial presentation, which spontaneously resolved upon clinical improvement. Therefore, HPVG may be regarded as a precursor to IE, as in a previous report [16].

The histological features of IE include (1) variable ulcer depth, typically extending to the submucosa or proper muscle layer; (2) ulcer bases lined with granulation tissue rich in vessels; (3) substantial fibrosis within the submucosal layers; (4) severe inflammatory-cell infiltration consisting of lymphocytes and plasma cells; and (5) scattering of hemosiderin-laden macrophages throughout all the layers of the intestine [3, 6, 8]. In this study, histological features were consistent with IE, with ulcers extending to the proper muscle layer and exhibiting inflammatory-cell infiltration and fibrosis, except for the multiple longitudinal ulcers in Case 3. The typical macroscopic feature of IE is a circumferential ulcer; however, a previous case series demonstrated a variety of configurations, including annular, geographic, and longitudinal ulcers [3].

The reported cases of IE may increase owing to the aging global population, increased in vascular risk factors, and advancements in imaging techniques, such as DBE. This may lead to the identification of specific IE features that can be detected via less invasive tests.

In conclusion, clinicians and surgeons should consider IE in patients with small bowel obstruction and segmental strictures without apparent acute ischemia, especially in older patients with severe comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or thromboembolic diseases.

Human rights

The authors declare that this study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Yuya Kondo and Shingo Tsujinaka. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Yuya Kondo. The manuscript was critically reviewed by Toru Nakano, Yu Katayose, and Chikashi Shibata. All authors read, commented, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.