-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Phan Tuấn Nghĩa, Trần Thiết Sơn, Phạm Thị Việt Dung, Tạ Thị Hồng Thuý, Đặng Phương Nam, Lê Diệp Linh, Reconstruction facial sequelaes of NOMA with anterolateral thigh free flap: two case reports, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 6, June 2025, rjaf354, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf354

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

NOMA, or oral labial necrosis, is a severe condition characterized by significant facial tissue destruction and elevated mortality rates, particularly in developing regions. Survivors often experience significant long-term consequences, leading to both functional and aesthetic impairments. The reconstruction of NOMA sequelae poses considerable challenges, including issues related to volume deficits, bone defects, and contracture deformities. This report presents two cases in which chimeric anterolateral thigh (ALT) flaps were effectively applied to address complex defects. The versatility of the ALT flap facilitated the reconstruction of multiple components, encompassing skin coverage, volume augmentation, and mucosal lining. This methodology offers a single-stage solution for reconstructing intricate NOMA sequelae, resulting in favorable functional and aesthetic outcomes.

Introduction

NOMA (oral labial necrosis) is a severe infectious disease that leads to significant tissue destruction in the face and has a high mortality rate. Although it has nearly vanished from the Western world, it remains prevalent in many developing regions, including Africa, Latin America, and the Asia-Pacific area. During the acute phase of the infection, untreated patients have a mortality rate exceeding 90%. Among the ~10% of patients who survive this acute phase, many are left with serious long-term effects, resulting in significant facial defects that impact both function and aesthetics. These lesions often involve extensive soft tissue damage in the cheeks, upper lip, and lower lip, along with deformities and contractions of various maxillofacial tissues [1, 2]. The sequelae of NOMA present considerable challenges for plastic surgeons. The resulting volume deficits, bone defects, and contracture deformities caused by fibrotic scars necessitate the use of various materials for reconstruction. While local and adjacent flaps have been effectively utilized for some minor to moderate lesions, microsurgical flaps are more suitable for addressing extensive deformities and reducing the number of surgical procedures required. The flaps advanced by the authors, such as the anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap, radial forearm flap, and shoulder flap, have been employed as single skin flaps to cover lesions. However, since NOMA lesions often affect multiple layers, more complex reconstructions are needed. In the two cases we report, chimeric ALT flaps were used to address various components of the defects, including skin coverage, volume augmentation, and mucosal lining reconstruction.

Case reports

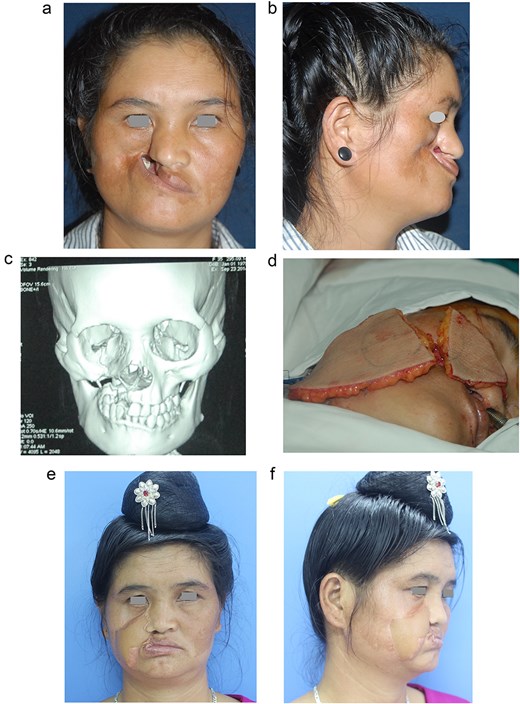

Case 1 (Fig. 1): A 35-year-old female patient presented with a facial infection 5 years ago, leading to a diagnosis of NOMA. She was treated at a provincial hospital, but after three weeks, she developed soft tissue and maxillary necrosis in the right cheek area. Subsequently, she was transferred to our department with a diagnosis of a right cheek soft tissue defect. The defect extended to the left cheek and left upper lip, deforming the right corner of her mouth and causing a partial loss of the right maxillary bone. As a result, the patient was unable to close her mouth properly. We planned to use an anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap from the left thigh to address the cheek defect and reconstruct the upper lip. We designed an ALT flap measuring 8 × 12 cm. During the procedure, we dissected two perforators originating from the descending branch of the lateral circumflex femoral artery (LCFA), with lengths of 7 and 9 cm. The two flaps were thinned from 25 to 10 mm in thickness. The skin flap was then divided into two skin islands, measuring 5 × 8 cm and 7 × 8 cm, corresponding to the areas that required coverage inside the mouth and on the outer skin. We also transferred part of the lower lip to create the upper lip and reconstruct the corner of the mouth while removing an unsightly scar in the cheek area. The flap was elevated, and the pedicle was connected end-to-end to the facial vessels. A small skin island was used to cover the inside of the mouth. Postoperatively, the flap survived well without any complications. A follow-up examination three years later revealed that the flap's color had remained unchanged, and the facial contours were still symmetrical. The patient's lip movements returned to normal, and the skin in the oral cavity was epithelialized appropriately. The patient was satisfied with the surgical results and successfully reintegrated into her community.

A 35-year-old female patient with NOMA diagnosed in the right maxilla, causing deformity and retraction of the upper lip and right cheek. (a and b) Preoperative images, front and lateral view, respectively. (c) X-ray of the maxillary lesion. (d) The harvested ALT flap, measuring 12 × 8 cm, with two perforators. The flap was divided into two skin islands based on two separate perforators to cover the outer skin and the inner oral cavity. (e and f) Results 3 years after surgery, upright and lateral, respectively.

Case 2 (Fig. 2): A 35-year-old female patient presented with a history of an infection in the left cheek area that occurred eight years before, for which she was treated at a provincial hospital. Upon evaluation, the patient exhibited deformity of the left cheek and contraction of the left corner of the mouth. The scarring had resulted in contraction of the left upper lip, deficiency in the lip mucosa, concavity of the left cheek, and a partial defect of the left maxilla. The patient was scheduled to undergo surgery using an anterolateral thigh (ALT) flap to reconstruct the soft tissue of her left cheek and augment its contour. The ALT flap, harvested from the left thigh, measured 5 × 11 cm and was perfused by two perforating vessels, with a descending branch measuring 7 cm. A secondary skin flap, measuring 4 × 5 cm, was created to cover the left cheek. The second flap was de-epithelized and inserted under the skin of the left cheek. The flap was elevated and microsurgically anastomosed to the left facial artery. The skin flap successfully encompassed the soft tissue defect, while the adipofascial component required augmentation of the left cheek. Additionally, a fascial flap was employed to cover the oral mucosa. Postoperative observation revealed that the flap demonstrated adequate survival, with no complications reported. Three months following the surgical procedure, the flap resulted in a balanced facial profile characterized by normal scarring.

35-year-old female patient diagnosed with NOMA in the left maxilla. Deformed lesion, contracture of the left corner of the mouth, scar contracture of the left upper lip, left cheek hollow. (a) Preoperative image of the lesion; (b) X-ray film of the maxillary bone lesion; (c) ALT flap measuring 11 × 5 cm, used to cover the soft tissue combined with partial de-epithelized aera to create cheek augmentation; (d) Results after 3 months.

Discussion

Surgical intervention to address the sequelae of NOMA presents significant challenges. Surgery requires careful planning, with numerous meticulous steps and stages. Rakhorst et al. published a study on the methods of reconstructing the sequelae of NOMA. They proposed the necessary reconstructive goals: to release the scar, resolve the trismus condition, and reconstruct the deficient tissue. The author also stated that the defects caused by the sequelae of NOMA are often significantly larger than the original shape, and the scar tissue, in this case, should be considered similar to irradiated tissue [1]. There have been previous studies choosing the materials to reconstruct the defects caused by the sequelae of NOMA, including lip-cheek flaps (Karapandzic, nasolabial fold flaps, etc.), temporalis musculocutaneous flaps, Delta thoracic flaps, submental flaps, radial forearm fascia flaps, and fasicocutaneous ALT flaps. However, the above materials still show many limitations, such as requiring many surgical stages (temporal fascia flap, Delta muscle flap) or causing severe damage to the donor site (radial forearm fascia flap). Many authors choose the submental flap for cheek and lip defects. The flap is designed as a pedicle flap in the form of a myocutaneous (taking the geniohyoid muscle), and the oral cavity lining is recreated due to the epithelialization on the muscle surface of the flap [3–5]. Although the flap is practical in surgery, it is bulky initially, combined with the limited flap pedicle and flap size, making it difficult for the submental flap to reach various lesions. The above local and regional flaps remain a suitable choice for mild lesions, particularly in limited surgical conditions and countries with underdeveloped economies. Free flaps are often mentioned less frequently by authors, mainly due to equipment limitations and their application to large and complex lesions.

Free flaps have been reported for reconstructing NOMA, such as the radial forearm flap, TRAM flap, latissimus dorsi flap, scapular flap, or the conventional ALT fasciocutaneous flap [6–9]. These flaps provide a large surface area and flexibility in the flap pedicle and may include muscle tissue. However, they do come with certain disadvantages. For instance, there may be a lack of uniformity in flap thickness. If a full-thickness defect is present, recreating the mucosal lining can be challenging unless local or regional flaps are used in combination. Additionally, secondary contraction may occur when skin or mucosal grafts are employed to form the lining [10]. Some flaps can also lead to significant morbidity at the donor site. The free ALT flap is a familiar material for reconstructing soft tissue defects. The flap has many advantages, especially for limb or trunk injuries and head and neck reconstruction. The ALT flap is a free flap characterized by a rich perforator system that originates from various sources. This structure enables the creation of independent flaps based on a single main vascular pedicle, specifically the descending branch of the LCFA, which can include skin, fascial, and muscle components. The design and customization of each flap component are straightforward and can be tailored according to the reconstruction's purpose, including the creation of three-dimensional facial structures [11]. Additionally, chimeric ALT flaps comprise different skin islands, enabling us to utilize thinning techniques that significantly mitigate the disadvantage of thick flaps. In cases involving the sequelae of NOMA, the deficiency may not be limited to a single layer of tissue but can involve full-thickness loss over a large area. In our experience, we harvested chimeric ALT flaps with two separate flaps in both cases. One skin flap was utilized for surface coverage, thinned to an average thickness of 1 cm, while the remaining flap was employed to create the lining or augment the defect area, as in the first patient. To reconstruct the lining layer, the flap fascia can be utilized as in the second case. The fascia at the base of the flap can cover internal defects without the need for skin grafting. The fascia demonstrates excellent tolerance to oral fluids. After two months, the entire lining layer has fully epithelialized. The ability to reconstruct multiple components of the defect using a single flap harvest during the same operation is a significant factor that has not been previously highlighted. Each skin flap in the chimeric configuration is customized to serve different purposes. For instance, when increased soft tissue volume is necessary, the flap is de-epithelized and augmented under the skin of the cheek area. Alternatively, if lining reconstruction is required, the skin flap is directed toward the oral cavity.

The ALT flap offers several advantages, including consistent anatomy, a secure blood supply, a long vascular pedicle, and the ability to harvest multiple components, such as fascia, muscle, and fat. It can be used for covering, 3D contouring, or augmenting purposes. Additionally, it has less morbidity at the donor site. In both cases, the primary goal was soft tissue reconstruction with the ALT flap, and reconstruction of the bony structure was unnecessary as it had no impact on mouth movement.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.