-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gabriella Donaldson, Aleisha Sutherland, Chylous ascites discovered intraoperatively during laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallstone pancreatitis, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 5, May 2025, rjaf281, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf281

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We present the first reported case of incidental intraoperative chylous ascites at the time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallstone pancreatitis. Our patient was managed successfully with dietary intervention and made a complete recovery.

Introduction

Chylous ascites is an uncommon clinical condition characterized by triglyceride-rich fluid in the peritoneal cavity arising from the thoracoabdominal lymphatic system [1].

The pathogenesis is attributed to disruption of lymphatic flow, broadly categorized into congenital abnormality, traumatic and post-operative injury, obstruction, infection, or inflammation [2]. The most common cause of chylous ascites in the Western adult population is abdominal malignancy, which leads to chyle leak by way of obstruction and/or direct invasion of lymphatic vessels [3].

Both acute and chronic pancreatitis have been described infrequently in the literature as causes of chylous ascites, with the proposed mechanisms being direct damage or compression of lymphatic vessels or by way of iatrogenic injury during interventions related to pancreatitis [4].

We describe below a rare case of chylous ascites associated with pancreatitis, diagnosed unexpectedly at the time of inpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Case report

A 58-year-old female presented with epigastric pain and a lipase of >1500 U/l. Her background included obesity (BMI 35) and Type II Diabetes Mellitus. She had no previous abdominal operations and denied alcohol consumption. A biliary ultrasound showed cholelithiasis within a thin-walled gallbladder and a normal common bile duct.

She was diagnosed and managed with gallstone pancreatitis on the surgical ward with analgesia, fluid, and supportive measures with the intention to proceed with index admission laparoscopic cholecystectomy once pain-free and systemically well.

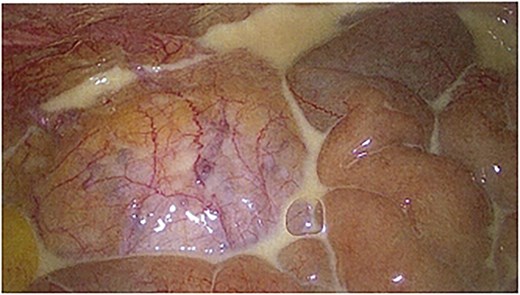

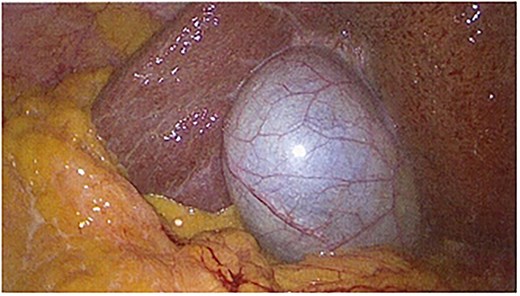

On day 4 of admission, she progressed to theatre for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. On entry to the abdominal cavity, milky/purulent fluid appeared in all four quadrants (Fig. 1). A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed to try to identify the cause of this. Her pelvic organs, caecum, transverse, and sigmoid colon were unremarkable. The small bowel was examined in its entirety, revealing no abnormality. The stomach and duodenum were inspected and were normal. There was saponification of the fat overlying the pancreas, and adhesions were present from the liver to the abdominal wall. The gallbladder was thin-walled (Fig. 2). No alternative source of peritonitis was identified; therefore, the decision was made to proceed with the cholecystectomy, which was uncomplicated. A 15 French Blake drain was placed in the pelvis.

Laparoscopic image showing chyle found on entry to the peritoneal cavity.

Laparoscopic image showing a thin-walled gallbladder prior to cholecystectomy.

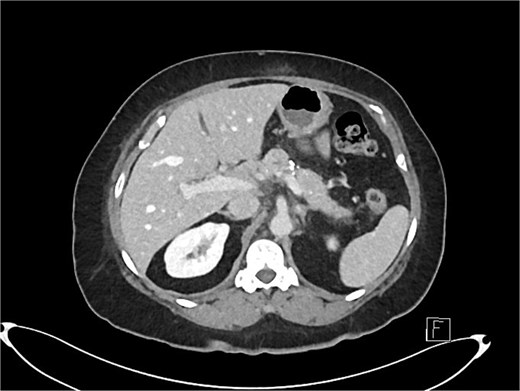

Post-operatively, a CT multiphase liver showed calcifications within the pancreas consistent with chronic pancreatitis, but there was no lymphadenopathy, no evidence of malignancy, and the rest of the abdominal organs were unremarkable in appearance (Fig. 3).

Axial slice of post-operative CT scan showing features of chronic pancreatitis.

A sample of the fluid was sent for culture, and this did not reveal any organisms or growth. This was also tested for tuberculosis; however, it was negative for acid-fast bacilli. A cytology report did not show granulomas or malignant cells but had a markedly raised triglyceride content of 16.3 mmol/l. Thus, a diagnosis of chylous ascites was made.

After dietician involvement, the patient commenced a low-fat, high-protein diet, and the drain outputs began to decrease. She was discharged from the hospital on day 9 post-operatively, with the drain that had been placed in the theatre remaining in situ. An outpatient MRI pancreas showed only mild mesenteric oedema. She was serially reviewed in the outpatient clinic, and the drain was removed three weeks post-operatively after no further chylous output was observed.

Discussion

Chylous ascites can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality, as leakage of chyle results in electrolyte disturbances, loss of proteins, lipids, fat-soluble vitamins, immunoglobulins, and lymphocytes [2].

The key diagnostic criteria is a triglyceride level > 2.13 mmol/l in sampled ascitic fluid [5]. CT and MRI, while not specific, are useful in identifying masses, collections or abnormal lymph nodes [6].

The mainstay of treatment lies with correcting the underlying cause and nutritional optimization, focusing on the restriction of long-chain triglycerides and instead consumption of medium-chain triglycerides in order to reduce the production of chyle. Medium-chain triglycerides are absorbed by the enterocytes and transported directly to the liver as free fatty acids and glycerol, therefore sparing the lymphatic system. This contrasts with long-chain triglycerides, which are transported as chylomicrons in the intestinal lymphatic system [2]. A more intensive approach of complete fasting with total parenteral nutrition may be considered in patients who fail initial dietary modification, although there is conflicting evidence as to whether this is any more effective [7].

The use of somatostatin analogues such as octreotide has been described in more refractory cases [2]. Octreotide has been shown to reduce portal pressure by its inhibition of glucagon, to reduce splanchnic vasodilatation and to reduce peristalsis and absorption of fats and triglyceride concentration in the thoracic duct [2]. Other uncommon therapeutic options include surgical ligation and embolization of disrupted lymphatic channels [8].

As mentioned previously, chylous ascites occurs infrequently as a result of pancreatitis, thought secondary to compression and damage of lymphatic vessels or due to iatrogenic injury [4]. A literature search on Medline revealed only seventeen case reports of chylous ascites caused by acute pancreatitis. Our report is unique as it is the only case where chylous ascites was discovered incidentally at the time of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Conclusion

In summary, this unique and interesting case highlights the key factors in the diagnosis and management of chylous ascites, particularly the use of a surgical drain and implementation of a low-fat diet, which led to a full recovery in our patient.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the patient for giving consent to discuss her case, as well as to Ms Jenny Wagener and Dr Anna Brownson for the laparoscopic images.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.