-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Wael Hashem, Hasan Khalili, Hossam Salameh, Bilateral persistent sciatic artery presenting as critical limb ischemia: a case report and review of literature, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 5, May 2025, rjaf242, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf242

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Persistent sciatic artery is a rare congenital vascular anomaly that presents with various clinical features, management planning depends on the aneurysmal changes, symptoms, and anatomical features of PSA and SFA. Asymptomatic cases can be managed with observation, while for more complicated cases, surgical or endovascular intervention is needed.

Introduction

Persistent sciatic artery (PSA) is a congenital vascular anomalous phenomenon in which failure of regression of the embryological sciatic artery occurs, leading to its persistence to compensate for the underdeveloped femoral artery or due to idiopathic etiologies [1].

During embryonic development, lower limb buds receive blood from arteries originating from the dorsal umbilical arteries, which eventually anastomose with the femoral artery. The sciatic artery, also from the same origin, usually regresses as it minimally aids lower limb perfusion [1].

However, in rare instances, estimated to be between 0.025% and 0.04% according to angiographic studies, the persistence of the sciatic artery can present with various clinically significant complications, typically manifesting as a mass in the gluteal region, leg, or buttock pain, or claudication, there have also been instances where it was associated with congenital anomalies [1–3].

Case report

A 49-year-old woman known case of essential thrombocythemia (ET) on hydroxyurea chemotherapy, presented with a seven-month history of left calf and foot pain that occurred at rest and was managed conservatively with a muscle relaxant and painkillers. The pain was provoked by walking and has progressively worsened, limiting walking distance to ten meters. Additionally, the patient noted bluish discoloration along the left leg, as well as black discoloration affecting the plantar surface of the left foot, heel, and nails. The patient has a long history of smoking with a 27-year pack history. Her past medical history is also significant for a well-controlled type II diabetes mellitus diagnosed ten years ago, as well as a partial thyroidectomy performed 6 years prior.

On physical examination, the left lower limb appeared cold, cyanotic, and mottled with a black discolored foot. While the femoral pulse was palpable, the popliteal, posterior tibial, and dorsalis pedis pulses were absent. Capillary refill was delayed, though no ulcers were present. The right lower limb exhibited normal pulses and no signs of ischemia.

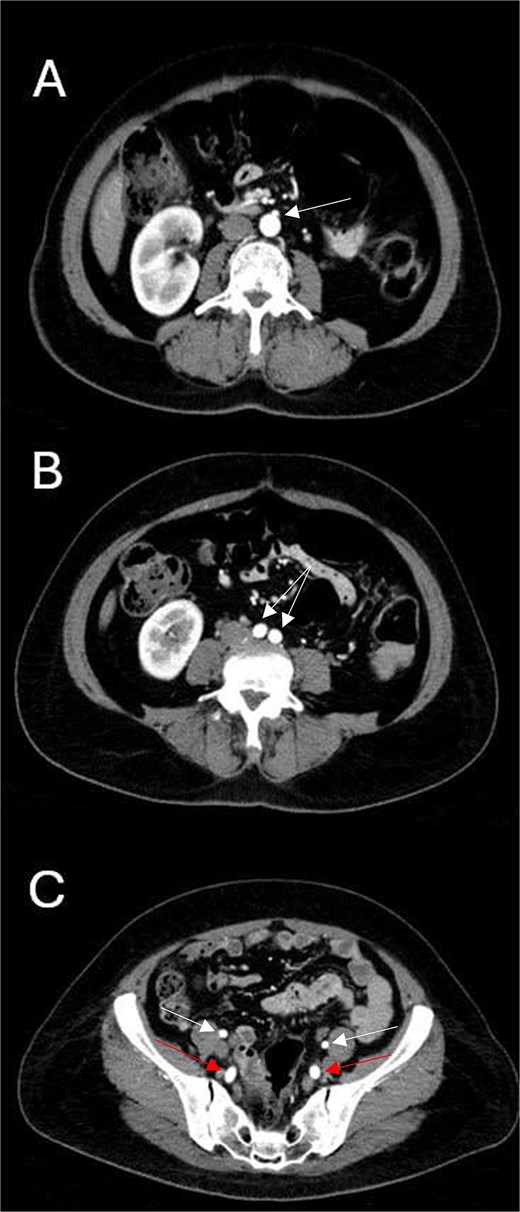

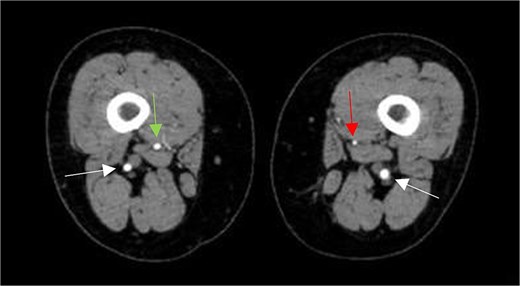

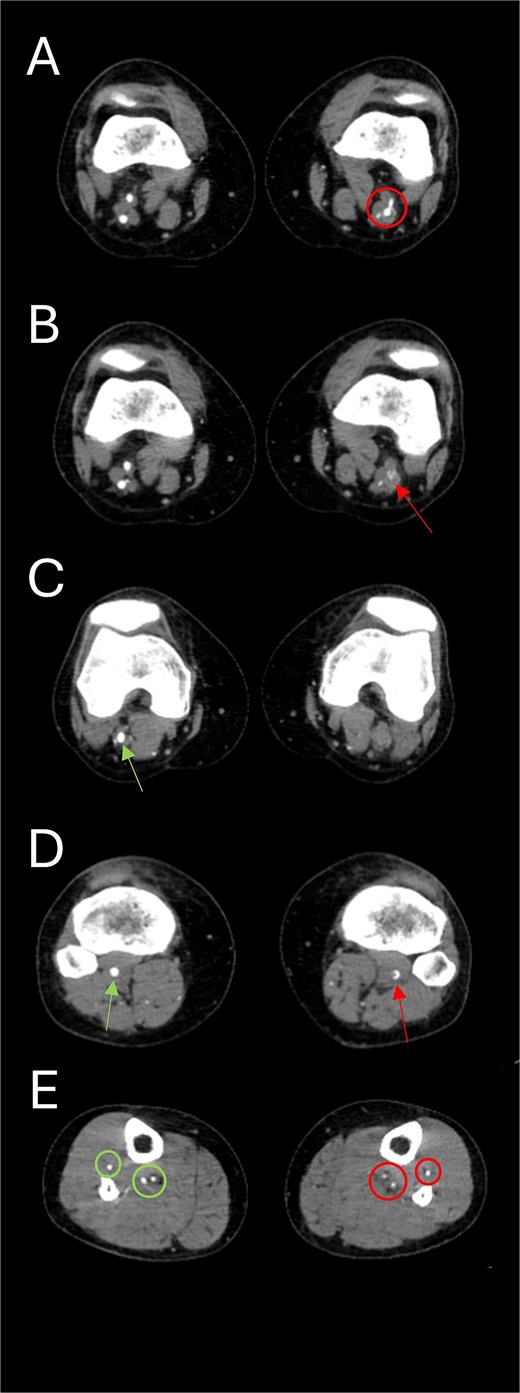

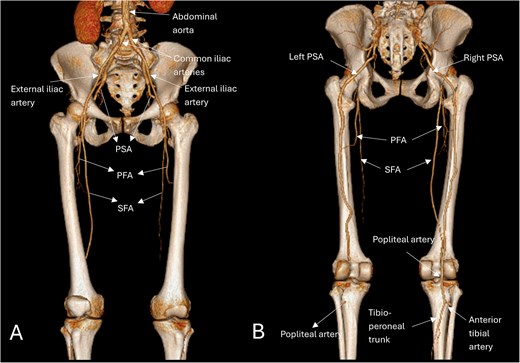

Subsequently, the patient underwent computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the lower extremities which revealed bilateral PSA (Fig. 1). The common femoral arteries trifurcated normally (Fig. 2), but the left superficial femoral artery (SFA) was significantly narrowed (Fig. 3). At the level of the knee, the right SFA joined the PSA to form the popliteal artery (Fig. 4). On the left side, the hypoplastic SFA converged with the PSA more proximally (Fig. 4); however, the artery was occluded, with no clear continuation into the popliteal artery (Fig. 4). Nevertheless, a markedly sub-occluded left popliteal artery was noted at the level of the fibular head, giving rise to a hypoplastic anterior tibial artery and tibio-peroneal trunk (Fig. 4). These findings align with Ahn-Min’s type I bilateral PSA (Fig. 5).

Axial CTA images show (A) the level of inferior mesenteric artery’s take-off from the abdominal aorta; (B) normal abdominal aortic bifurcation into common iliac arteries; and (C) bilateral prominent internal iliac arteries (lower arrows) and normal external iliac arteries (upper arrows).

Axial CTA image shows normal femoral trifurcation (circles) and prominence of bilateral PSAs (arrows).

Axial CTA image shows hypoplastic left SFA along its course in the adductor canal (vertical arrow on left leg), but normal-sized right SFA (vertical arrow on right leg), and bilateral prominent PSAs (horizontal arrows).

Axial CTA images show (A) the union of the left SFA and SFA; (B) occluded left popliteal artery; (C) the absence of the left popliteal artery and the emergence of the right popliteal artery from the union of right SFA and PSA; (D) the presence of a sub-occluded left popliteal artery (arrow on right leg) at the level of the fibular head and a normal right popliteal artery (arrow on left leg); and (E) the presence of hypoplastic left tibial and peroneal arteries (circles on left leg) along their course in the left leg compared to normal-sized arteries in the right leg (circles on right leg).

Three-dimensional reconstructed anatomic views anteriorly (A) show a narrowed left SFA, while the right SFA appears normal, both arising from the common femoral artery; and posteriorly (B) show the bilateral prominent PSAs as a continuation of the internal iliac arteries, the right SFA merges with the PSA as it supplies the dominant circulation of the right lower limb, the left PSA is occluded distally with no continuation into the popliteal artery; however, below the fibular head, a tibioperoneal trunk is present. Based on Ahn-min’s classification, this lower limb arterial pattern was consistent with type-I bilateral PSA.

Accordingly, the patient underwent a non-complicated peripheral angioplasty with thrombectomy via right femoral access. A catheter-directed thrombectomy was performed using a Fogarty balloon catheter, with a heparin infusion initiated post-procedure. She remained hemodynamically stable throughout her stay, and heparin was discontinued on postoperative day 2. Bilateral intact pulses, warm feet, and good capillary refill time were noted at discharge. The patient was prescribed a medication regimen including aspirin, clopidogrel, rivaroxaban, atorvastatin, and hydroxyurea for her ET. She will be monitored conservatively moving forward.

Discussion

The case of bilateral PSA presenting with critical limb ischemia is a rare yet significant vascular anomaly that warrants thorough discussion.

Embryologically, the sciatic artery originates from the internal iliac artery and supplies the lower limb during early development [4]. It typically regresses by the third trimester and is replaced by the femoral artery [4]. If regression fails or femoral artery maturation is incomplete, PSA persists as a continuation of the internal iliac artery [4]. Its incidence is 0.025%–0.04%, with 30% of cases being bilateral [4].

PSA is a vascular anomaly that presents in varying forms, which can be broadly classified into complete or incomplete PSA, depending on its continuation with lower limb circulation. Complete PSA maintains a direct connection with the popliteal artery, and the SFA will be either hypoplastic (as in our patient) or absent [4].

In cases of incomplete PSA, the sciatic artery will be hypoplastic, and the SFA will serve as the dominant vessel supplying the lower limb [4].

PSA can be further classified according to Ahn-Min classification into four classes, as seen in Table 1 [5].

Comparison of Ahn-Min’s and Pillet-Gauffre’s classification systems of PSA based on the anatomy of the SFA and the presence of aneurysms [5].

| Ahn-Min’s classification . | PSA anatomy . | SFA anatomy . | Aneurysm . | Pillet-Gauffre’s classification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Complete | Complete | Absent | Types 1 and 5a |

| Class Ia | Complete | Complete | Present | |

| Class II | Incomplete | Complete | Absent | Types 3 and 4 |

| Class IIa | Incomplete | Complete | Present | |

| Class III | Complete | Incomplete | Absent | Types 2a, 2b, and 5b |

| Class IIIa | Complete | Incomplete | Present | |

| Class IV | Incomplete | Incomplete | Absent | None |

| Class IVa | Incomplete | Incomplete | Present |

| Ahn-Min’s classification . | PSA anatomy . | SFA anatomy . | Aneurysm . | Pillet-Gauffre’s classification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Complete | Complete | Absent | Types 1 and 5a |

| Class Ia | Complete | Complete | Present | |

| Class II | Incomplete | Complete | Absent | Types 3 and 4 |

| Class IIa | Incomplete | Complete | Present | |

| Class III | Complete | Incomplete | Absent | Types 2a, 2b, and 5b |

| Class IIIa | Complete | Incomplete | Present | |

| Class IV | Incomplete | Incomplete | Absent | None |

| Class IVa | Incomplete | Incomplete | Present |

Comparison of Ahn-Min’s and Pillet-Gauffre’s classification systems of PSA based on the anatomy of the SFA and the presence of aneurysms [5].

| Ahn-Min’s classification . | PSA anatomy . | SFA anatomy . | Aneurysm . | Pillet-Gauffre’s classification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Complete | Complete | Absent | Types 1 and 5a |

| Class Ia | Complete | Complete | Present | |

| Class II | Incomplete | Complete | Absent | Types 3 and 4 |

| Class IIa | Incomplete | Complete | Present | |

| Class III | Complete | Incomplete | Absent | Types 2a, 2b, and 5b |

| Class IIIa | Complete | Incomplete | Present | |

| Class IV | Incomplete | Incomplete | Absent | None |

| Class IVa | Incomplete | Incomplete | Present |

| Ahn-Min’s classification . | PSA anatomy . | SFA anatomy . | Aneurysm . | Pillet-Gauffre’s classification . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Complete | Complete | Absent | Types 1 and 5a |

| Class Ia | Complete | Complete | Present | |

| Class II | Incomplete | Complete | Absent | Types 3 and 4 |

| Class IIa | Incomplete | Complete | Present | |

| Class III | Complete | Incomplete | Absent | Types 2a, 2b, and 5b |

| Class IIIa | Complete | Incomplete | Present | |

| Class IV | Incomplete | Incomplete | Absent | None |

| Class IVa | Incomplete | Incomplete | Present |

According to Ahn-Min’s classification system, our patient has class I PSA recognized during our CT Angiography performed at the initial evaluation of her presenting symptoms.

Distinguishing between the different types of PSA has significant clinical implications, particularly when the PSA is the dominant artery [6]. While PSA cases are most commonly discovered incidentally, our patient was diagnosed in the context of symptomatic presentation consistent with critical limb ischemia, which constitutes 7.5% of cases when compared with the literature seen in Table 2 [5].

According to a literature review that studied 224 limbs, these are the anatomical and clinical manifestations [5].

| Literature review cases (224 limbs) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of PSA | Complete | Incomplete | |||

| 184 (86.8%) | 28 (13.2%) | ||||

| Types of SFA | Complete | Incomplete | Absent | ||

| 29 (13.7%) | 170 (80.2%) | 13 (6.1%) | |||

| Patency of PSA | Patent | Stenosis | Occlusion | ||

| 124 (63.3%) | 18 (9.2%) | 54 (27.5%) | |||

| Type according to Pillet-Gauffre’s classification | 1 | 2a | 2b | 3 | Unclassifiable |

| 17 (8.2%) | 155 (74.9%) | 9 (4.3%) | 13 (6.3%) | 13 (6.3%) | |

| Aneurysmal formation | Present | Absent | |||

| 112 (50.7%) | 109 (49.3%) | ||||

| Symptoms | Incidental | Buttock mass and pain | Intermittent claudication | Critical limb ischemia | Acute limb ischemia |

| 63 (29.6%) | 45 (21.1%) | 41 (19.4%) | 16 (7.5%) | 38 (17.8%) | |

| Treatment | Medical/Observation | Open surgical | Endovascular | Hybrid procedures | |

| 68 (35.8%) | 74 (39.0%) | 31 (16.3%) | 17 (8.9%) | ||

| Literature review cases (224 limbs) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of PSA | Complete | Incomplete | |||

| 184 (86.8%) | 28 (13.2%) | ||||

| Types of SFA | Complete | Incomplete | Absent | ||

| 29 (13.7%) | 170 (80.2%) | 13 (6.1%) | |||

| Patency of PSA | Patent | Stenosis | Occlusion | ||

| 124 (63.3%) | 18 (9.2%) | 54 (27.5%) | |||

| Type according to Pillet-Gauffre’s classification | 1 | 2a | 2b | 3 | Unclassifiable |

| 17 (8.2%) | 155 (74.9%) | 9 (4.3%) | 13 (6.3%) | 13 (6.3%) | |

| Aneurysmal formation | Present | Absent | |||

| 112 (50.7%) | 109 (49.3%) | ||||

| Symptoms | Incidental | Buttock mass and pain | Intermittent claudication | Critical limb ischemia | Acute limb ischemia |

| 63 (29.6%) | 45 (21.1%) | 41 (19.4%) | 16 (7.5%) | 38 (17.8%) | |

| Treatment | Medical/Observation | Open surgical | Endovascular | Hybrid procedures | |

| 68 (35.8%) | 74 (39.0%) | 31 (16.3%) | 17 (8.9%) | ||

According to a literature review that studied 224 limbs, these are the anatomical and clinical manifestations [5].

| Literature review cases (224 limbs) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of PSA | Complete | Incomplete | |||

| 184 (86.8%) | 28 (13.2%) | ||||

| Types of SFA | Complete | Incomplete | Absent | ||

| 29 (13.7%) | 170 (80.2%) | 13 (6.1%) | |||

| Patency of PSA | Patent | Stenosis | Occlusion | ||

| 124 (63.3%) | 18 (9.2%) | 54 (27.5%) | |||

| Type according to Pillet-Gauffre’s classification | 1 | 2a | 2b | 3 | Unclassifiable |

| 17 (8.2%) | 155 (74.9%) | 9 (4.3%) | 13 (6.3%) | 13 (6.3%) | |

| Aneurysmal formation | Present | Absent | |||

| 112 (50.7%) | 109 (49.3%) | ||||

| Symptoms | Incidental | Buttock mass and pain | Intermittent claudication | Critical limb ischemia | Acute limb ischemia |

| 63 (29.6%) | 45 (21.1%) | 41 (19.4%) | 16 (7.5%) | 38 (17.8%) | |

| Treatment | Medical/Observation | Open surgical | Endovascular | Hybrid procedures | |

| 68 (35.8%) | 74 (39.0%) | 31 (16.3%) | 17 (8.9%) | ||

| Literature review cases (224 limbs) . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of PSA | Complete | Incomplete | |||

| 184 (86.8%) | 28 (13.2%) | ||||

| Types of SFA | Complete | Incomplete | Absent | ||

| 29 (13.7%) | 170 (80.2%) | 13 (6.1%) | |||

| Patency of PSA | Patent | Stenosis | Occlusion | ||

| 124 (63.3%) | 18 (9.2%) | 54 (27.5%) | |||

| Type according to Pillet-Gauffre’s classification | 1 | 2a | 2b | 3 | Unclassifiable |

| 17 (8.2%) | 155 (74.9%) | 9 (4.3%) | 13 (6.3%) | 13 (6.3%) | |

| Aneurysmal formation | Present | Absent | |||

| 112 (50.7%) | 109 (49.3%) | ||||

| Symptoms | Incidental | Buttock mass and pain | Intermittent claudication | Critical limb ischemia | Acute limb ischemia |

| 63 (29.6%) | 45 (21.1%) | 41 (19.4%) | 16 (7.5%) | 38 (17.8%) | |

| Treatment | Medical/Observation | Open surgical | Endovascular | Hybrid procedures | |

| 68 (35.8%) | 74 (39.0%) | 31 (16.3%) | 17 (8.9%) | ||

In the context of critical limb ischemia, it has been reported that 31%–63% of the PSA cases had lower limb ischemia, with up to 25% manifesting as critical limb ischemia [4]. This is concordant with the values found in Table 2 where about 75% presented with symptoms of limb ischemia [5].

PSA aneurysms constitute the most common complication, occurring in about half of patients as demonstrated in Table 2, and can be complicated by thrombosis, rupture, embolization, or sciatic nerve compression [5]. However, our patient did not develop an aneurysm; instead, they had developed atherosclerosis in the left PSA, which progressed into complete occlusion at the level of the knee.

PSA management often requires a multidisciplinary approach, including imaging to confirm and investigate the vascular anatomy, followed by potential surgical or endovascular interventions to restore perfusion [7].

Ahn et al. in a systematic review proposed a management strategy, according to the anatomical variants, completeness of PSA and SFA, and the presence of aneurysms [5].

Shown in Table 3 are the proposed treatment options for each class [5].

| AHN-Min’s classification . | Recommended treatment . |

|---|---|

| I | Optimal medical therapy |

| Ia | Embolization |

| II | Optimal medical therapy |

| IIa | Embolization |

| III | Bypass + ligation of proximal popliteal artery to the distal anastomosis |

| IIIa | Bypass + ligation of proximal popliteal artery to the distal anastomosis + embolization |

| IV | Bypass |

| IVa | Bypass + embolization |

| AHN-Min’s classification . | Recommended treatment . |

|---|---|

| I | Optimal medical therapy |

| Ia | Embolization |

| II | Optimal medical therapy |

| IIa | Embolization |

| III | Bypass + ligation of proximal popliteal artery to the distal anastomosis |

| IIIa | Bypass + ligation of proximal popliteal artery to the distal anastomosis + embolization |

| IV | Bypass |

| IVa | Bypass + embolization |

| AHN-Min’s classification . | Recommended treatment . |

|---|---|

| I | Optimal medical therapy |

| Ia | Embolization |

| II | Optimal medical therapy |

| IIa | Embolization |

| III | Bypass + ligation of proximal popliteal artery to the distal anastomosis |

| IIIa | Bypass + ligation of proximal popliteal artery to the distal anastomosis + embolization |

| IV | Bypass |

| IVa | Bypass + embolization |

| AHN-Min’s classification . | Recommended treatment . |

|---|---|

| I | Optimal medical therapy |

| Ia | Embolization |

| II | Optimal medical therapy |

| IIa | Embolization |

| III | Bypass + ligation of proximal popliteal artery to the distal anastomosis |

| IIIa | Bypass + ligation of proximal popliteal artery to the distal anastomosis + embolization |

| IV | Bypass |

| IVa | Bypass + embolization |

Conclusion

Bilateral PSA is a rare congenital anomaly that can present with several complications, critical limb ischemia being one of them. Recognizing PSA as a potential cause of lower limb ischemia is very important, as misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis can markedly impact patient outcomes. Being aware of such an anomaly enables clinicians to tailor imaging strategies for appropriate identification and to differentiate PSA-related limb ischemia from other vascular pathologies. This, in turn, greatly affects treatment decisions, ensuring timely and appropriate intervention. As shown in this case, endovascular approach can be an effective and minimally invasive option for restoring perfusion. Long-term follow-up is essential to monitor for recurrence and optimize vascular health. Given the rarity, we advise colleagues who encounter similar cases to report their findings and their approach to management to provide more insight into such rare occurrences, thus contributing to the growing body of knowledge on PSA.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Rafidia Surgical Hospital, Nablus, Palestine, for their support in conducting the necessary clinical evaluations and imaging studies for this.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest to be mentioned.

Funding

None declared.

References

Author notes

Wael Hashem, Hasan Khalili and Hossam Salameh contributed equally to this article.