-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Damian Broadhurst, Sandra Campbell, Fazain Jarral, Damian Tolan, Richard P Baker, Left paraduodenal hernia: a rare cause of gastric outlet obstruction and large bowel obstruction, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 4, April 2025, rjaf209, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf209

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Paraduodenal hernia is a rare subset of internal hernia and an uncommon aetiology of bowel obstruction. A 50-year-old male presented with a 12 h history of severe epigastric pain and vomiting. A contrast enhanced computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated gastric outlet obstruction and large bowel obstruction due to left paraduodenal hernia involving the distal transverse colon and gastric antrum. After resuscitation, a laparotomy was performed, the bowel was reduced, the mesocolic defect repaired, and small bowel mesentery widened. The large bowel was decompressed via the appendix stump. The post-operative recovery was unremarkable. Left paraduodenal hernia is a rare condition and where seen acutely, usually presents with small bowel obstruction. Here the patient presented with a large bowel obstruction, a rare presentation of this uncommon condition. Operative intervention is mandatory in the acute setting to prevent ischaemia and perforation from strangulation of the bowel.

Introduction

Internal hernias occurs when a viscus protrudes through a mesenteric or peritoneal defect within the abdominal cavity [9]. Commonly the result of previous surgery, internal hernias may be congenital [10]. Paraduodenal hernias are the most common form of congenital internal hernias and may be left or right sided, each with a different embryological origin [11]. Left paraduodenal hernias result from failure of fusion of the transverse mesocolon with the parietal peritoneum and account for nearly 70% of paraduodenal hernias [2, 12]. The resulting space is eponymously named Landertz’s fossa, into which bowel can herniate. Right paraduodenal hernias are associated with small bowel non-rotation and result from a defect in the jejunal mesentery, eponymously named Waldeyer’s fossa, allowing small bowel to herniate into a sac inferolateral to the transverse mesocolon [2].

Here we present the case of left paraduodenal hernia resulting in gastric outlet and large bowel obstruction. Full informed and written patient consent was obtained for publication.

Case report

A 50-year-old male with no previous surgical history presented with a 12 h history of severe epigastric pain and vomiting. He had not opened bowels since the previous day. Examination revealed abdominal distension with epigastric tenderness and guarding.

Full blood count, renal and liver function and amylase were unremarkable.

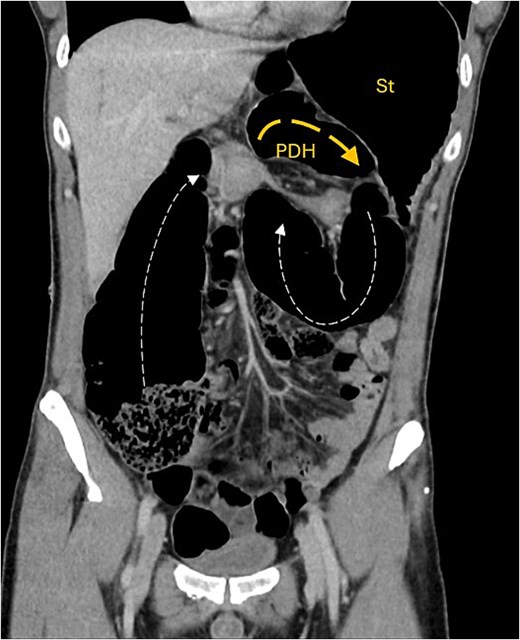

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a large bowel obstruction with a transition point at the distal transverse colon with swirling of the mesentery. Downstream large bowel was collapsed. Upstream dilatation included the terminal ileum suggested an incompetent ileo-caecal valve. The gastric antrum was also involved in the internal hernia, resulting in gastric outlet obstruction. See Figs 1–5.

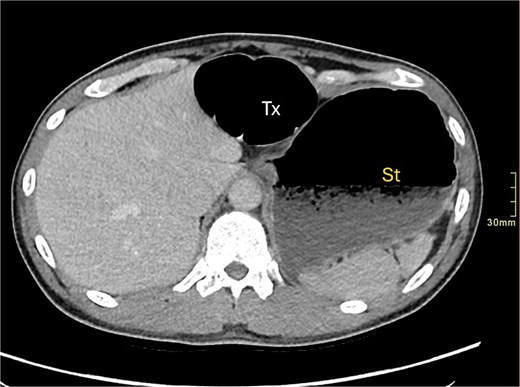

Axial CT image demonstrating distended transverse colon (Tx) and stomach (st).

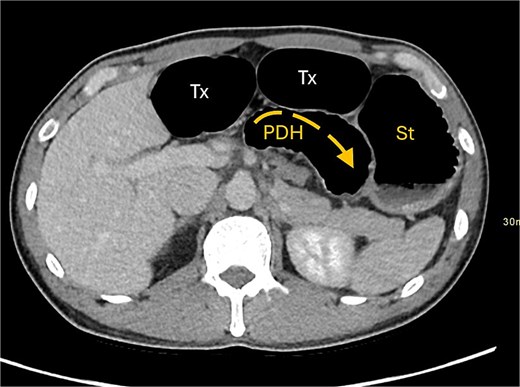

Axial CT image displaying transverse colon in paraduodenal hernia (PDH) with resulting distension of transverse colon (Tx) and stomach (st).

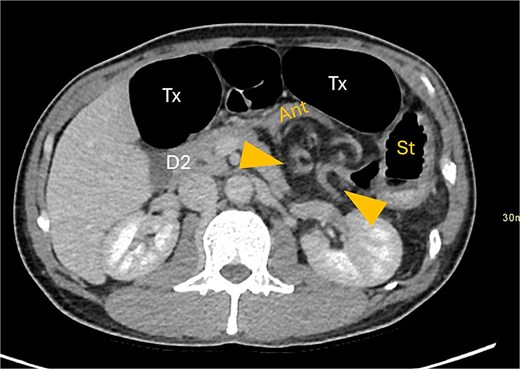

Gastric outflow obstruction of stomach (st) from compression of antrum (ant) by herniated transverse colon. Hernia between arrows.

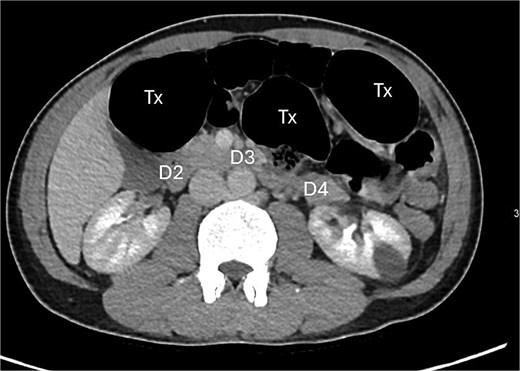

Posterior displacement of the duodenum (D4) due to herniated transverse colon.

Coronal CT image showing obstructed transverse colon (Tx) path (small dash arrow), looping posteriorly through narrow hernia neck into anterior PDH containing Tx colon segment (wide dash arrow). Stomach (st) is distended.

Intestinal obstruction is a common presentation but paraduodenal hernia is an uncommon cause of obstruction. It more frequently results in small rather than large bowel obstruction [1–8].

Resuscitative care was initiated which included placement of a nasogastric tube, intravenous fluid resuscitation, analgesia, and antiemetics.

During resuscitation, the patient’s pain increased. Serum lactate from a venous blood gas sample was 2.45 mmol/L despite intravenous fluid resuscitation. The decision was made to proceed to laparotomy immediately.

At laparotomy the proximal transverse colon and hepatic flexure were found herniating through the left paraduodenal recess into the lesser sac (Fig. 6). The herniating segment of large bowel was reduced. This segment was healthy and viable. A wide paraduodenal recess, narrow small bowel mesentery and mobile transverse colon exacerbated the herniation tendency into the lesser sac.

Intra-operative image demonstrating mesocolic defect through which the transverse colon had herniated.

The paraduodenal recess was narrowed with three interrupted 2–0 non-absorbable monofilament sutures to the mesenteric peritoneum. It was noted that the base of the small bowel mesentery was short, increasing the risk of total small bowel volvulus. To prevent this, the base of the small bowel mesentery was widened by division of the mesenteric peritoneum. The grossly distended large bowel could not be decompressed into the small bowel and stomach to the nasogastric tube and the ileocaecal valve was found to be competent. An appendicectomy was performed and the large bowel was decompressed with suction via the appendix stump. The appendix stump was then ligated and buried in the caecum with 3–0 absorbably monofilament purse-string suture. Thorough washout of the abdominal cavity was performed and the abdomen closed.

The patient remained an inpatient for 5 days with gradual reintroduction of oral intake and mobilization. The patient was reviewed in the outpatient clinic at 6 weeks and had recovered and returned to normal activities.

Discussion

In this case, the patient’s main presenting complaint was one of abdominal pain. The symptoms are of paraduodenal hernia are non-specific. In this case the definitive diagnosis was made using CT imaging. Indeed, there are no pathognomonic symptoms or signs of paraduodenal hernia and case reports that pre-date the widespread use of CT imaging, the diagnosis was made during exploratory laparotomy [13].

Initial management should be as for any patient with bowel obstruction; nasogastric tube drainage, fluid resuscitation and close monitoring of fluid balance and electrolytes. The timing of operative intervention should be decided based on the presence of perforation or bowel ischaemia as well as the patient’s symptoms. In our case the patient had no radiological signs of bowel ischaemia and at laparotomy all bowel was viable. In other reported cases, internal hernia strangulation has resulted in need for bowel resection and in some cases, stoma formation [1, 4, 8]. This would suggest that early operative intervention may preclude the need for bowel resection, as per other case reports.

We hypothesize that opting for contrast-enhanced CT imaging early facilitated early diagnosis and permits early intervention to salvage threatened bowel or prevent the sequalae of intra-abdominal sepsis in the case of viscus perforation. Delay in definitive diagnosis and intervention has been reported to result in increased morbidity in published cases [2, 4, 8].

Laparoscopic approaches to paraduodenal hernia repair are described in the literature, both with and without mesh [6, 12, 14, 15]. Rates of laparoscopic repair approached one third in a recent systematic review [12]. In our case, an open approach was taken due to surgeon familiarity with the approach and ease of access, particularly in the context of distended large bowel. No mesh was placed, with the defect closed using non-absorbable sutures.

Decompression of distended large bowel via the appendix stump is a safe technique for large bowel decompression that does not require formation of an enterotomy. In the case of large bowel obstruction with a competent ileocaecal valve, the appendix stump gives access to the large bowel lumen for decompression.

In conclusion, our case presentation demonstrates that paraduodenal hernias can lead to large bowel obstruction when the mobile transverse colon herniates through a mesocolic defect and into Landertz’s fossa. Small bowel obstruction is more commonly reported in the literature and our case represents a rare presentation of a rare condition.

Paraduodenal hernias are rare and have non-specific signs and symptoms. Prompt CT investigation allows for early recognition of compromised bowel and early intervention to prevent necrosis, perforation and resulting intra-abdominal sepsis.

Surgical repair of paraduodenal hernias is mandatory to prevent recurrence and subsequent morbidity from strangulation and perforation.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.