-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Yoshihiro Kawaguchi, Mitsunori Matsuo, Naoki Ito, Yusuke Mori, Shinichi Maekawa, Shingo Tsuneyoshi, Yusuke Okayama, Hidehiro Ishii, Tsukasa Igawa, Synchronous cancers including parathyroid carcinoma with urinary calculus as the initial sign, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 3, March 2025, rjaf121, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf121

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Hyperparathyroidism with urinary calculus as the initial symptom is common; however, carcinomas of the parathyroid gland are rare. Moreover, synchronous cancers have rarely been reported. A man in his 50s presented to our hospital with a 1-month history of left lumbar back pain. After close examination, urinary calculus, parathyroid carcinoma, and lung cancer were detected. He underwent surgical treatment followed by additional anticancer drugs. Two and a half years following his first visit to our hospital, no recurrence has been observed. Parathyroid carcinoma should be considered as a cause of urinary calculus, and synchronous cancers, including rare cancer, can also exist.

Introduction

Hyperparathyroidism causes urinary calculus in ⁓1% of cases, and parathyroid carcinoma occurs in 1%–5% of these cases [1]. Only three cases of synchronous cancers, including parathyroid carcinoma, have been reported [2]. In the present case, a thorough examination of the urinary calculus identified parathyroid carcinoma, along with synchronous lung cancer. Here, we present the second reported case of synchronous cancers involving the parathyroid gland and lungs [3].

Case report

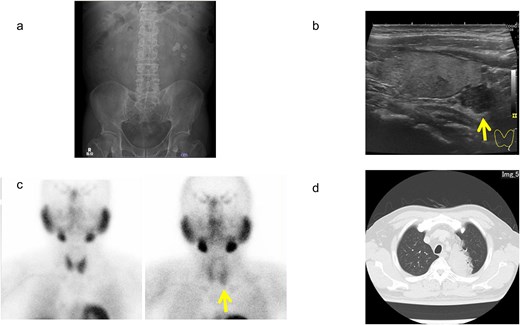

A man in his 50s presented to our hospital with a 1-month history of left lumbar back pain. He had a smoking history of 40 cigarettes per day from age 20 until the time of his hospital visit. He had no history of pancreatic tumors and no specific family history. Kidney–ureter–bladder radiography and computed tomography (CT) revealed a left ureteral calculus (23 mm × 17 mm) and a right renal calculus (Fig. 1a). Blood tests showed hypercalcemia (11.0 mg/dL; normal range: 8.8–10.1 mg/dL) and elevated intact-parathyroid hormone (PTH) (202 pg/mL; normal range: 10–65 pg/mL) levels. The urinary calcium-to-creatinine (Ca/Cre) ratio was elevated at 0.3. Cervical ultrasonography showed a well-defined adenoma in the left inferior thyroid, measuring 18 mm × 12 mm, and we consulted with the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism (Fig. 1b). 99mTc-methoxy isobutyl isonitrile scintigraphy showed accumulation at the same site during the delayed phase, and a parathyroid tumor was suspected (Fig. 1c).

Imaging findings of urinary calculus, as well as parathyroid and lung lesions. (a) Kidney–ureter–bladder radiograph. (b) Ultrasonography of the cervix. (c) 99mTc-methoxy isobutyl isonitrile scintigraphy. (d) Chest computed tomography. Arrows indicate tumor areas.

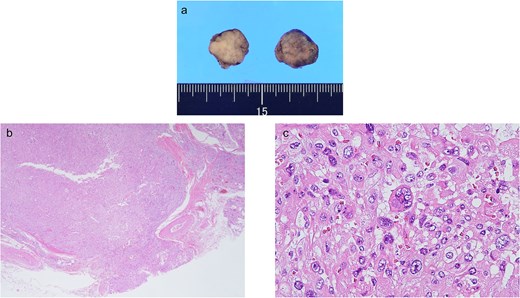

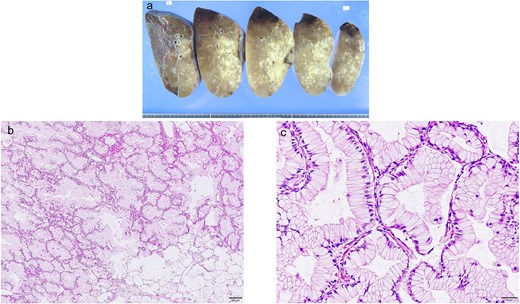

Considering the benign parathyroid tumor, we decided to prioritize treatment for the ureteral stone, which was causing mild renal hypofunction and pain. The patient opted to undergo ureteroscopy (URS) owing to the difficulty of living with a nephrostomy. A total of URS procedures were performed on the right and left sides, resulting in the resolution of the ureteral calculi. Stone analysis revealed a composition of >98% calcium oxalate. Two months following the completion of stone treatment, the patient underwent a left inferior parathyroidectomy. Pathological examination confirmed a diagnosis of parathyroid carcinoma, based on findings of extracapsular invasion, despite a Ki67 index of ⁓3% (Fig. 2). As part of a thorough examination of the parathyroid gland, a CT scan of the parathyroid gland revealed a lung tumor (Fig. 1d). A biopsy was performed using endobronchial ultrasound, with findings suggestive of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma. Additional positron emission tomography-CT showed mild accumulation in the left upper lobe, with no findings indicative of metastasis to the mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes. Four months after completion of stone treatment, a left lobectomy with mediastinal and hilar lymph node dissection was performed. The patient was diagnosed with invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma, staged as pT4N0M0 (Fig. 3). Based on the pathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with synchronous cancers involving localized parathyroid carcinoma and pT4N0M0 stage IIIA invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma. Following parathyroidectomy, the urinary Ca/Cre ratio improved, and blood calcium and intact-PTH levels normalized within the standard range. His lung cancer was treated with four courses of postoperative chemotherapy using cisplatin and vinorelbine, followed by additional courses of maintenance therapy with atezolizumab. Two and a half years have passed since the initial diagnosis. No recurrences of urinary calculus, parathyroid carcinoma, or lung cancer have been observed.

Gross and pathological findings of the parathyroid carcinoma. (a) The excised left lower parathyroid gland. (b) Pathologically, the fibrous septum was broken, and extracapsular infiltration was observed (magnification 2×). (c) A mixture of multinucleated and megakaryocytes was observed (magnification 400×).

Gross and pathological findings of the lung cancer. (a) Gross findings with segmented lungs. (b, c) Tumor cells form glandular duct structure with alveolar epithelial replacement. (b) Median (magnification 100×) and high-power (magnification 400×) images.

Discussion

This case report highlights two important points. First, parathyroid carcinoma can present with urinary calculus as an initial sign. Second, synchronous cancers, including rare cancers, can also exist.

Parathyroid carcinoma is present in 0.5%–5% of cases of primary hyperparathyroidism [1]. A calcium level exceeding 14 mg/dL, a serum PTH level greater than four times the upper limit of normal, and the presence of a cervical mass, reporting in 70% of cases, are clinical features that can help differentiate parathyroid carcinoma from a benign parathyroid tumor [4]. Bone symptoms, such as osteoporosis and fractures (45.8%); renal symptoms, such as renal and urinary calculus and renal failure (37.2%); as well as fatigue (13.6%), are reportedly the most common symptoms of parathyroid cancer [5]. A definitive diagnosis requires pathological evidence of invasion or metastasis [6]. Parathyroid carcinoma accounts for ⁓0.005% of all malignancies [7]. Although there is no standard four-stage classification system for parathyroid carcinoma, it can be categorized into localized, metastatic, and recurrent types based on clinical and pathological findings [4]. The present case was diagnosed as localized parathyroid carcinoma. In principle, the treatment involves complete surgical tumor removal. In many cases, such as in our case, the malignancy is identified postoperatively [1]. Patient survival rates are reportedly 76%–85% at 5 years and 49%–77% at 10 years [8]. An association between urinary calculus and parathyroid carcinoma was considered for the following reasons. Stone analysis indicated that the stones were composed of calcium oxalate. Improvements were observed in serum calcium and intact-PTH levels, as well as in the urinary Ca/Cre ratio. One and a half years following URS surgery, the patient remained free of stones, with no recurrence.

In this case, the presence of urinary calculus led to the discovery of localized parathyroid carcinoma and pT4N0M0 stage IIIA lung cancer. No pathological association was identified between the parathyroid carcinoma and lung cancer. Three cases of synchronous cancers have been reported: thyroid cancer alongside parathyroid carcinoma and lung cancer alongside parathyroid carcinoma [2]. This is the second reported case of synchronous cancers of the parathyroid and lung [3].

Conclusion

Although the probability of encountering urinary calculus with parathyroid carcinoma is low, parathyroid carcinoma may be the cause of urinary calculus. Serum Ca and intact-PTH levels, along with a history of bone lesions, should be considered [5, 9].

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.