-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Adrián M Oviedo, Gerardo A Dávalos, Gabriel A Molina, Diana E Parrales, Mauricio R Heredia, Santiago Muñoz-Palomeque, Chronic pericarditis secondary to pericardial lymphangioma. An unusual presentation of an unusual tumor: case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 2, February 2025, rjaf075, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf075

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Pericardial lymphangiomas are exceptionally rare and affect both children and adults. Although they are usually asymptomatic, they can cause symptoms secondary to the mass effect, from syncope or palpitations to arrhythmia or congestive heart failure. The most reliable diagnostic methods are echocardiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging, with subsequent confirmation by histopathology. Its treatment consists of complete surgical resection. We present the case of a 2-year-old female patient with a definitive diagnosis of pericardial lymphangioma who debuted with cardiac tamponade and hemodynamic repercussions. She underwent a pleuropericardial window by lateral thoracotomy with resection of nodular masses at the posterior level of the pericardium without complications. The patient's evolution and prognosis were favorable.

Introduction

Primary tumefactive pericardial lesions include pericardial cysts, mature teratomas, and lymphangiomas, which, despite being benign, may cause clinical symptoms that require resolution [1]. Mediastinal cysts are benign lesions found in adulthood and childhood [2].

Pericardial lymphangiomas, on the other hand, are benign hamartomatous malformation-type tumors composed of aggregates of lymphatic vessels, which are considered aberrant embryogenic remnants due to blockage of the lymphatic system during fetal development or which develop secondary to an obstruction [3–6].

These tumors are tremendously rare, with few individual case reports in the medical literature, usually presenting in children. Intrapericardial lymphangioma is exceptionally rare [3–5].

Case report

A 2-year-old female patient with no known medical history presented with tachycardia, respiratory distress, hepatomegaly, jugular engorgement, and muffled heart sounds suggestive of cardiac tamponade, with effacement of the costophrenic angles and a cardiothoracic index of 0.66 on chest X-ray. An echocardiogram confirmed significant diffuse pericardial effusion, with an anterior layer measuring 24 mm and a posterior layer measuring 77 mm, with a right pleural effusion (Fig. 1), and with hemodynamic repercussions. We performed subxiphoid pericardial drainage, obtaining 550 ml of serosanguineous characteristics with moderate amounts of loose tissue and showing thickening of the pericardium. Cytochemical analysis indicated exudate results with no bacterial growth in the fluid culture and pericardial tissue, after which the patient remained in the intensive care unit for 7 days. Before removing the pericardial drainage tube, we performed a new echocardiogram, showing little residual fluid, after which the patient was discharged home.

Chest X-ray (A) and echocardiogram (B & C) with evidence of pleural and pericardial effusion.

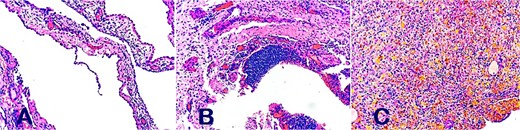

A follow-up echocardiogram 15 days after discharge showed a moderate recurrence of pericardial effusion, with hyperechoic nodular images at the posterior level, without causing hemodynamic repercussions, so a pleuropericardial window was made by lateral thoracotomy with drainage and sample analysis, where a thickened pericardium was evident, with the presence of nodular masses of 2 cm in diameter, between 6 and 8 units, with abundant bloody tissue adhered to the inner surface of the posterior pericardium which was resected, and 100 ml of serohematic pericardial fluid was drained. The histopathological analysis of pericardial tissue showed characteristics of papillary endothelial hyperplasia compatible with pericardial lymphangioma (Fig. 2).

Histopathological analysis of papillary endothelial hyperplasia compatible with pericardial lymphangioma on (A, B, and C).

Patient in subsequent follow-up in adequate conditions, without new symptoms or recurrences.

Discussion

Lymphangiomas are benign congenital anomalies that may develop anywhere the lymphatic system is located, however, they rarely present as a unilocular or multilocular mediastinal cystic mass, while the involvement of the pericardium is extremely rare [6, 7]. In this line, pericardial and cardiac lymphangiomas are exceptionally rare and affect both children and adults [5].

These tumors are usually asymptomatic but can cause symptoms secondary to the mass effect, depending on the location and degree of involvement, and range from syncope or palpitations to arrhythmia or congestive heart failure [4, 5].

The most common symptoms include dyspnea and chest pain due to the mass effect exerted by the lesion on adjacent cardiac structures [8].

For diagnosis, initially, the chest X-ray may show a widening of the cardiac contour; However, the most reliable imaging methods are echocardiography with findings of hyperechoic mass with cystic and septal components, while computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offer a characterization of the mass, showing cystic and septal components without calcifications or macroscopic fat [1, 3].

In the study by Pichler Sekulic and Sekulic [3], they examined and presented the histopathological, clinical, and radiological characteristics of 74 cases of cardiac/pericardial lymphangiomas, and reported that they were identified in both children and adults and, if they were symptomatic, the patients more frequently exhibited respiratory distress/dyspnea. Likewise, the X-ray findings of a widened cardiac silhouette stand out, and the echocardiogram generally reported a hyperechoic mass with cystic and septal components. In the CT and MRI, cystic and septal components were again reported, and the CT showed an absence of calcifications or macroscopic fat. Most lymphangiomas had a pericardial base (specifically visceral) and were frequently located in the right atrioventricular groove. Most cases underwent surgical resection with no evidence of postoperative recurrence.

These findings can be corroborated and compared with our case, supporting again that the characteristics of this rare tumor are related to the symptoms of mass effect consisting of dyspnea and, even in our case, pericardial effusion. Besides, invasion of the visceral surface of the pericardium is a frequent location in its presentation.

Most cases are managed by complete surgical resection, which generally results in a good prognosis without postoperative recurrence [1, 3, 4]. The thoracoscopic approach significantly reduces the duration of the surgical intervention and the postoperative hospital stay of the patient [9].

The pericardial window procedure is used in the treatment of pericardial lymphangiomas to relieve symptoms caused by pericardial effusion or mass effect by opening the pericardium to allow drainage of fluid accumulated in the pericardial space into the pleural cavity, which reduces pressure on the heart and improves symptoms. The pericardial window can be performed by video-assisted thoracoscopy, allowing excellent visualization and accurate selection of biopsy sites, as well as minimizing complications associated with classic surgical procedures [10].

In patients with mediastinal cysts, the prognosis after complete excision is excellent, and the morbidity and mortality rates associated with surgery are low [2].

Conclusion

When a patient comes to the emergency room with symptoms compatible with pericardial effusion of non-traumatic origin, especially in the pediatric age group, the clinical suspicion includes several differential diagnoses. In this context, the suspicion of pericardial and cardiac tumors should not be omitted, and pericardial lymphangioma, although a tumor of rare presentation, should be considered as one of the possible options since its definitive resolution will mainly be surgical.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.