-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Christian Rios, Sergio Verboonen, Jeffry Romero, Jaime Ponce de Leon, Alex Guachilema Ribadeneira, Marginal ulcer perforation after one anastomosis gastric bypass: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 2, February 2025, rjaf073, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf073

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

One anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) has gained popularity and it is currently the third most frequently performed bariatric procedure worldwide. A marginal ulcer (MU) at the anastomosis site between the gastric pouch and the small intestine is a common complication of gastric bypass procedures but a rare complication of OAGB. Risk factors for MUs include cigarette smoking, alcohol misuse, and Helicobacter pylori infection. MU symptoms include abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting; however, some patients are asymptomatic. MU perforations are repaired as follows: laparoscopy with or without ulcer debridement, omental patch closure, conversion into Y gastric bypass, or reoperation. This report describes MU perforations in two patients after OAGB.

Introduction

One anastomosis gastric bypass (OAGB) is a safe and effective intervention for weight loss and reduction of co-morbidities and a more straightforward procedure than Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB); however, the potential for postoperative complications is a cause for concern [1]. OAGB outcomes include durable weight loss (77% of patients at 5 years), reduction of co-morbidities (80% of patients), and improved control of type 2 diabetes and hypertension (67% of patients). The percentage of patients with anastomotic leaks or marginal ulcers (MUs) is 1% and 3%, respectively. Internal hernias occur but they are uncommon. The OAGB mortality rate is 0.1% [2]. The main complications associated with OAGB include biliary reflux, MUs, and malnutrition [1]. The number of case reports with a focus on MUs and treatment options is limited. This report describes the MU perforations that occurred in two patients and the surgical management.

Case 1

A 24-year-old woman underwent OAGB 6 years before presenting for evaluation of a 70% unintentional weight loss. She smoked one pack of cigarettes and drank six beers daily for the past 12 months. She was admitted to our hospital with a 5-d history of intense epigastric pain and was treated with omeprazole. The pain had intensified over the previous 24 h. The physical examination was significant for a heart rate of 118 beats per min, and a distended abdomen with pain to palpation suggestive of peritonitis. Laboratory examinations indicated leukocytosis (19 000 leukocytes/uL), 85% polymorphonuclear cells, serum albumin of 4.0 mg/dl, and intraperitoneal free air on abdominal ultrasound.

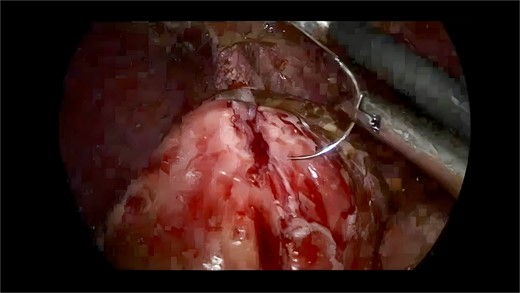

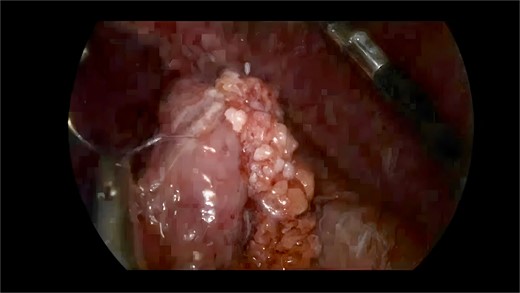

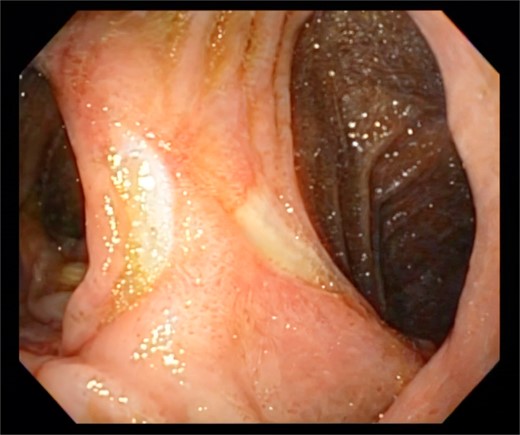

Exploratory laparoscopy revealed a large amount of intestinal fluid, fibrinous exudates, edematous intestinal loops, and a 1-cm MU at the level of the gastrojejunal anastomosis (Fig. 1). The margins were debrided and the defect was closed with absorbable poliglecaprone using a continuous suture technique. The closure was reinforced by an omental patch (Figs 2 and 3). The abdominal cavity was aspirated and irrigated. She was discharged from the hospital without complications. An endoscopy 6 months postoperatively revealed a persistent MU (Fig. 4).

Case 2

A 27-year-old man with a history of methamphetamine and cocaine misuse was admitted to our hospital with a 24-h history of abdominal pain, fevers, diaphoresis, and nausea. He had undergone an OAGB 1 y before presentation. Physical examination of the abdomen was consistent with generalized peritonitis. Subdiaphragmatic air was noted on abdominal X-ray.

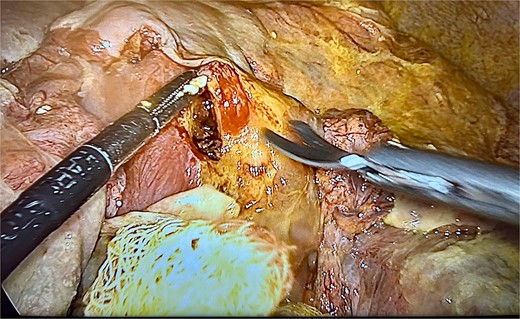

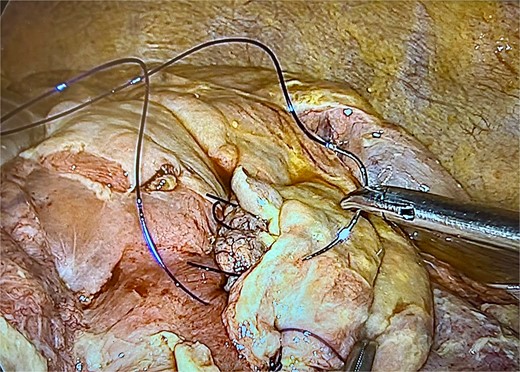

Exploratory laparoscopy revealed approximately 2000 mL of purulent fluid and an MU perforation (Fig. 5). The defect was repaired as described above, followed by abdominal cavity aspiration and irrigation (Figs 6 and 7). He remained in the intensive care unit for 48 h with symptomatic improvement and was discharged 6 d postoperatively.

Discussion

OAGB is the third most frequently performed bariatric procedure worldwide. Although a rare complication of OAGB, MUs occur at the gastro-jejunal anastomosis, typically on the anti-mesenteric side of the jejunum [2]. MUs may cause bleeding and perforation [3]. The etiology of OAGB-associated MUs has not been established but risk factors for MUs include stress, cigarette smoking, Helicobacter pylori infection, and alcohol misuse.

The incidence of MUs is 0.6%–2.6% [1, 4]. First-line treatment of MUs involves elimination of known risk factors and proton pump inhibitors [5], whereas MUs that do not heal spontaneously, MUs that are refractory to medications, or complex MUs are treated surgically. MU perforations are rare and caused by stress, use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and discontinuation of proton pump inhibitors. Effective treatments for MU perforations are a matter of debate but include resection with or without omental patch closure or conversion to RYGB [1].

An MU perforation should be considered in patients who undergo OAGB and have abdominal pain. Common symptoms of an MU perforation include acute abdominal pain, fevers, tachycardia, and elevated inflammatory markers. MU perforations are confirmed by the presence of free air in the abdomen on abdominal radiography or computed tomography [1].

Minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery is the preferred surgical method for MU perforations. Surgical options should be selected based on the patient’s health status, the site and size of the perforation, the degree of contamination, and surgical experience.

Small perforations can be repaired with suturing and omental patch closure. Large perforations with infected margins should be treated with RYGB or reoperation. Abu-Abeid et al. [5, 6] performed primary surgical resection and omental patch closure in 86% of patients with MU perforations. Abdominal lavage, drain placement, and PPI therapy should be considered in all cases [5, 6].

MU perforations are a rare but potentially lethal complication of gastric bypass surgery. The perforation size, quality of adjacent tissues, and presence of localized or generalized peritonitis should be assessed carefully. Surgical decisions should be based on the patient's hemodynamic and nutritional status, laboratory results, co-morbidities, and other clinical parameters.

This case demonstrates that laparoscopic resection with omental patch closure for OAGB complicated by MU perforation is safe with good outcomes.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.