-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Raed Alshalfan, Sami Almalki, Mohammed Alnasser, Abdullah Alhaqbani, Case report: chronic expanding hematoma becomes angiosarcoma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 2, February 2025, rjaf063, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf063

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Chronic expanding hematoma is a hematoma that gradually increases in size over a period. Only a few studies reported a chronic expanding hematoma that turned into a malignancy, we report a rare presentation of a chronically expanding hematoma that after 10 years became an angiosarcoma. This is a 41-year-old gentleman, presented to our Emergency Department, complaining of left upper gluteal pain and bleeding after he underwent hematoma evacuation in a private hospital. The patient was then admitted for infected hematoma evacuation. The patient tolerated the surgery; however, there was a persistent drop of hemoglobin postoperatively. All pathology and culture results were inconclusive. We then proceeded with computer tomography angiogram, which came back negative. Magnetic resonance imaging was then requested, which came with a slight interval change and a suspicious area, and so interventional radiology was involved to take a biopsy, which came back as angiosarcoma and then the patient underwent wide local excision with reconstruction.

Introduction

Chronic expanding hematoma is defined as a hematoma—blood outside blood vessels—that gradually increases in size over a period of 1 month or more [1]. Hematomas usually go away spontaneously; however, some do not resolve and cause mass effect to surrounding tissues and might need surgical intervention [1]. Chronic expanding hematoma can present in many locations, most commonly trunk and extremities and sometimes can turn into a neoplasm [2, 3]. Only few studies reported a chronic expanding hematoma that turned into a malignancy, we report a rare presentation of a chronically expanding hematoma that after 10 years became an angiosarcoma.

Case presentation

This is a 41-year-old gentleman not known to have any medical illnesses, presented to our emergency department (ED) complaining of left sided lower back/upper gluteal area pain and bleeding for 3 days after he underwent hematoma evacuation in a private hospital.

The patient sustained a trauma to the left gluteal region 10 years ago in a road traffic accident and since then the hematoma was stable and no intervention was needed. Three months before his presentation to the private hospital, he started to have pain and discomfort at his left gluteal/upper back region. He went to a private hospital where he was diagnosed with a localized hematoma by computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The patient then underwent two hematoma evacuations surgeries that were both unsuccessful. He was having persistent bleeding from the hematoma site, so he decided to come to our ED.

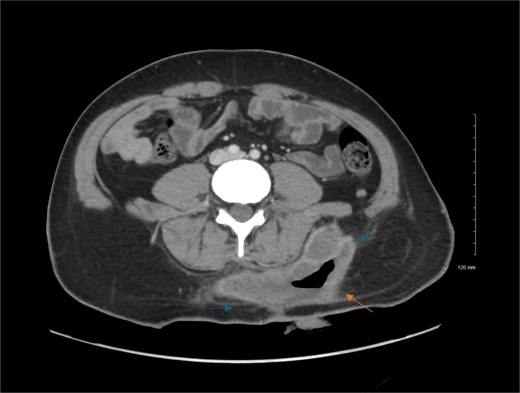

At the time of the presentation, the patient looked well, in mild pain but not in distress, vitally and clinically stable. Upon examination, there were two right gluteal incisions, measuring 15 cm and the lateral incision measuring 3 cm. The area was swollen, surrounded by erythema and fluctuant, mildly tender to touch. Laboratory findings were unremarkable. With the patient’s presentation, we proceeded with CT scan that showed infected gluteal hematoma (Fig. 1).

Contrast enhanced axial CT scan of the abdomen. Contrast enhanced CT scan of the abdomen shows left lower back fluid collection with peripheral thick wall enhancement (blue arrows), consistent infected collection. There is also air seen within the collection (orange arrow), indicating prior attempted evacuation.

The patient was then admitted under the care of general surgery for infected hematoma evacuation. The patient tolerated the surgery; however, there was persistent drop of hemoglobin (Hg) postoperatively from 93 to 67 g/L although the procedure went well with adequate hemostasis. The patient was then shifted to the operating room yet again for exploration that was insignificant and did not explain the drop in Hg. Specimens were taken from the wound for culture and histopathology, and hemostasis was achieved.

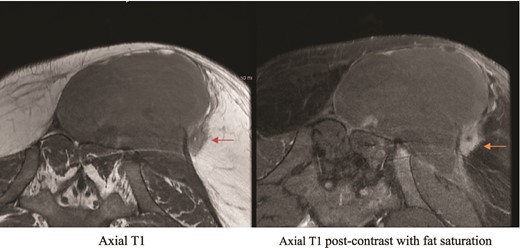

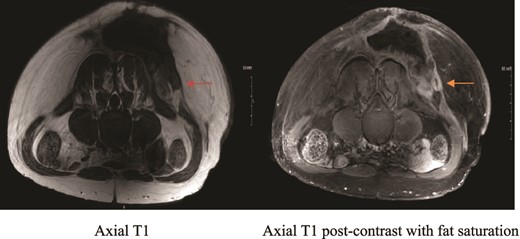

All pathology and culture results were inconclusive, and the patient kept having a drop in Hg, which was managed by blood transfusion. We then proceeded with CT angiogram to delineate the blood supply of the area and to look for possible contrast extravasation, which came back negative. MRI was then requested to rule out soft tissue masses. The MRI result came with unspecific findings but when compared with previous MRI taken in the private hospital, there was slight interval change and a suspicious area, and so interventional radiology were involved to take a deep ultrasonography guided biopsy (Figs 2 and 3).

Private hospital MRI. Axial T1 MRI (left) shows left rounded low T2 signal intensity lesion (orange arrow), which shows hyperenhancement (green arrow) on axial T1 fat saturated postcontrast images (right).

MRI showing suspicious lesion. Postoperative MRI images show re-demonstration of suspicious lesion when correlated to prior MRI from private hospital. The lesion shows low T1 signal intensity (orange arrow), and post-contrast enhancement with central linear area of non-enhancement.

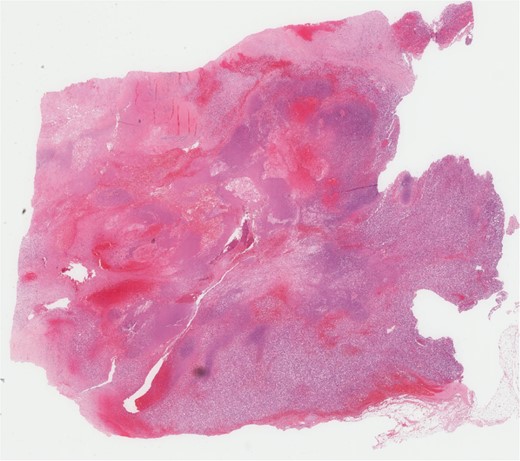

Biopsy results came back as angiosarcoma and the patient was then transferred under the care of orthopedic oncology for wide local excision (WLE), and plastic surgery joined for skin grafting and coverage of the wound (Fig. 4).

Microscopic pathology confirming the diagnosis. Pathology report: five cores of white to gray-tan soft tissues, the smallest measuring 0.4 × 0.1 × 0.1 cm and the largest measuring 1.3 × 0.1 × 0.1 cm. Diagnosis: angiosarcoma.

A second operation was needed as the first one had a positive margin. The second surgery came with negative margins and the patient was kept in the hospital to take care of the skin graft and to continue the course of antibiotics. The case was discussed in the Musculoskeletal Tumor Board Meeting to decide whether the patient needs chemotherapy/radiotherapy before proceeding with skin flap. After discussion, the decision was made that since the patient does not have any metastasis and with the negative margins from the WLE, chemotherapy is not necessary at this time and the patient will benefit more from local radiotherapy 4–6 weeks from the last surgery before proceeding with skin flap. Day 14 postoperatively, the patient was seen fit to be discharged and to be followed up by orthopedic oncology, plastic surgery, and radiation-oncology to terminate the tumor.

Discussion

This is a rare presentation of angiosarcoma, and that can explain the difficulty the team faced to get to the diagnosis. Chronic expanding hematomas are rare, and it is even rarer for them to turn into a neoplasm. The cause of the hematoma in this case is similar to any hematoma that is usually a blunt trauma; however, the reason for being chronically expanding is still unknown [4]. Same with the reason behind this hematoma becoming a neoplasm and, in this case, an angiosarcoma. Similar to other case reports, this case presented after a long period of time (10 years), and it was after a blunt trauma to the gluteal region. The reason for the diagnosis to be made in the private hospital could be due to poor multiple specialties communication, which is not the case in a tertiary hospital setting. The reason behind the normal pathological findings in the first biopsy taken could be explained by that it was not taken deep and near to the bed of the tumor. MRI could be a helpful tool in diagnosing such cases but most importantly, a high level of suspicion is the most important tool. The reason and the pathogenesis behind such conditions has to be studied more.

Conclusion

Chronic expanding hematoma is a rare condition, and less common is becoming a neoplasm. Investigations such as MRI are helpful to diagnose such conditions but most importantly a high level of suspicion. Multi-specialties team and good communication between them can help facilitate the diagnosis faster and result in a better outcome to the patient. The pathophysiology behind chronic expanding hematoma is yet to be described.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dr Ali Assiri, consultant pathology in King Abdulaziz Medical City for providing us with the pathology slides.

Author contributions

Dr Abdullah Alhaqbani (Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Writing and editing Final draft), Dr Raed Alshalfan (Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation), Dr Mohammed Alnasser (Data curation, Supervision), and Dr Sami Almalki (Conceptulalization, Project administration, Supervision, Reviewing final draft).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre, reference number RYD-23-419812-169174.

References

- angiogram

- hemangiosarcoma

- magnetic resonance imaging

- lipoma

- hemorrhage

- biopsy

- cancer

- hematoma

- hemoglobin

- computers

- emergency service, hospital

- hospitals, private

- pain

- interventional radiology

- reconstructive surgical procedures

- surgical procedures, operative

- pathology

- surgery specialty

- eccrine acrospiroma

- persistence

- general surgery

- hematoma evacuation

- wide local excision