-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

McKenna L Schimmel, Maxwell D Mirande, Fazal W Khan, Stephanie F Heller, Daniel Stephens, Cholecystitis as a result of cecal herniation through the foramen of Winslow, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 2, February 2025, rjaf060, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf060

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Internal herniation through the foramen of Winslow is one of the rarest types of hernia. As signs and symptoms can be quite generalized, prompt identification can prove difficult, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. The majority of reported cases of foramen of Winslow herniation result in obstruction of either the small or large bowel requiring operative intervention. As they are so rare, there is no established treatment algorithm for foramen of Winslow hernias. We present here a unique case of cecal herniation through the foramen of Winslow resulting in biliary compression and acute cholecystitis without bowel obstruction that was managed with laparoscopic cholecystectomy and right hemicolectomy.

Introduction

Foramen of Winslow hernias (FWH), also known as Blandin’s hernias, are exceedingly rare, characterizing <0.1% of all hernias [1–3]. The epiploic foramen of Winslow allows for communication between the greater peritoneal cavity and lesser sac defined by the anatomic boundaries of the hepatoduodenal ligament, the inferior vena cava, the caudate lobe of the liver, and the 1st portion of the duodenum; however, standard intra-abdominal pressure typically keeps the viscera from herniating through the foramen [1, 3]. When herniation does occur, it is thought to be a result of excess visceral mobility, abnormal enlargement of the foramen, changes in intra-abdominal pressure, or rarely congenital malrotation [1, 3, 4]. Most reported cases note herniated ileum, cecum, or ascending colon at risk for bowel strangulation, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality reported as high as 49% [1–8]. Herein, we describe a case of cecal herniation through the foramen of Winslow resulting in biliary compression and acute cholecystitis without bowel obstruction.

Case report

An 80-year-old female with history of three cesarian sections and prior stroke on aspirin and ticagrelor presented to the emergency department with 1 day of acute nausea, vomiting, and right upper quadrant abdominal pain; surgical consultation was obtained. She denied any similar episodes, postprandial pain, or obstipation. Upon physical examination, she was afebrile, hemodynamically stable, and saturating well on room air. Her abdomen was soft with mild epigastric distention. She exhibited a positive Murphy's sign without signs of generalized peritonitis.

The patient’s laboratory values were significant for WBC 12.2 × 109/L, potassium 3.1 mmol/L, creatinine 0.59 mg/dl, lipase 676 U/L, total bilirubin 1.8 mg/dl, direct bilirubin of 0.6 mg/dL, ALT/AST 147/221 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase of 579 U/L. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast demonstrated the cecum herniating through the foramen of Winslow with no signs of ischemia or bowel obstruction (Fig. 1); the gallbladder was distended with pericholecystic stranding and surrounding portal triad inflammation (Fig. 2).

Two coronal images from a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast demonstrating the cecum herniating through the foramen of Winslow with no signs of ischemia or bowel obstruction.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast demonstrating a distended gallbladder with pericholecystic stranding and surrounding portal triad inflammation.

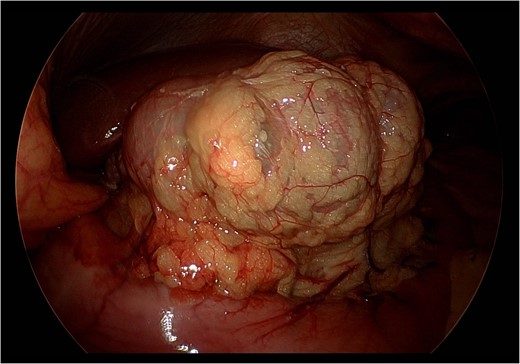

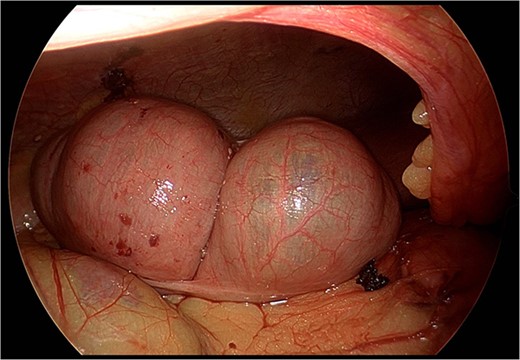

Upon laparoscopic exploration, the cecum was visualized herniating through the foramen of Winslow (Fig. 3), resulting in elevation of the portal structures and biliary compression. The gallbladder was distended with early signs of inflammation. There were no intraabdominal adhesions. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was executed in standard fashion after obtaining the critical view of safety. Afterwards, using a combination of traction and pushing, the cecum was laparoscopically reduced from the lesser sac (Fig. 4). Although the cecum did not appear ischemic or necrotic, the highly mobile cecum was resected to prevent future volvulus, obstruction, or strangulation. All trocars were then removed, and pneumoperitoneum was released. A small upper midline incision was made, and the cecum and small bowel were extracorporealized. A stapled side-to-side, functional end-to-end, anti-peristaltic ileocolonic anastomosis was performed with 60 mm purple Endo-GIA staplers. With blunt dissection, the foramen of Winslow defect was gently widened to prevent future bowel strangulation. The midline fascia was closed with two running 1 Stratafix sutures. The skin was closed with staples and covered with an incisional negative pressure wound therapy vacuum.

Still photograph obtained during exploratory laparoscopy demonstrating cecal herniation through the foramen of Winslow.

Still photograph obtained during exploratory laparoscopy demonstrating complete reduction of the cecum from the lesser sac without signs of ischemia or necrosis.

Immediately post-operatively, the patient demonstrated signs of improved liver function and decreasing biliary obstruction with laboratory values significant for total bilirubin 0.7 mg/dl, direct bilirubin of 0.4 mg/dl, ALT/AST 95/157 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase of 382 U/L. Given nausea and abdominal distention, the patient was started on a volume-restricted diet of clear liquids on post-operative Day 1. She was transitioned to a regular diet by post-operative Day 4 accompanied by return of bowel function. Laboratory values steadily normalized over the course of her hospitalization. At time of discharge on post-operative Day 6, the patient’s laboratory values were notable for WBC 10.7 × 109/L, potassium 3.6 mmol/L, creatinine 0.69 mg/dl, lipase 45 U/L, total bilirubin 0.5 mg/dl, direct bilirubin of 0.2 mg/dl, ALT/AST 42/47 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase of 241 U/L.

The patient was evaluated in our outpatient clinic 3 weeks post-operatively. The patient reported eating without nausea or vomiting and having full return to prior bowel function. She denied any fevers or chills since discharging from the hospital. Since that time, the patient has not had any recurrent episodes of herniation and is otherwise doing well from a gastrointestinal perspective.

Discussion

First described in 1834 by Blandin, the FWH is a rare form of internal hernia [6]. Of the roughly 200 cases reported in the literature, nearly all describe presentation with bowel herniation resulting in obstruction, often leading to formal bowel resection [1–12]. Very uniquely, this case did not present with obstruction, but rather as acute cholecystitis due to external biliary compression. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of its kind to be reported. The most closely related case consisted of herniation of the transverse colon resulting in compression of the portal vein and periportal lymphedema evident on CT [9].

Diagnosis of FWH is most commonly made intra-operatively, with less than 10% of cases having a pre-operative radiologic diagnosis [9–11]. Our patient had the benefit of evidence on CT scan expediting surgical intervention and avoiding further consequence of ongoing biliary obstruction and possible bowel obstruction and ischemia [10, 12]. Signs of cecal FWH on CT include absence of cecum in the normal anatomic position, mesenteric fat and vessels posterior to the portal structures, and a ‘bird’s beak’ formation of gas and/or fluid in the lesser sac pointing towards the epiploic foramen [3]. There is ongoing debate regarding whether prophylactic closure of the foramen or fixation of the mobilized viscera needs to be undertaken [1]. At the time of writing, there have been no documented recurrences of a FWH, with or without fixation. In our case, we elected to gently widen the foramen as well as resect of the hypermobile right colon to prevent further episodes of herniation or the possibility of cecal volvulus.

In conclusion, FWH are a rare type of internal hernia that often present with bowel obstruction and in our case, acute cholecystitis. Axial imaging is essential for expedited diagnosis and surgery intervention remains the standard of care for management.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

None declared.