-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Amy Tianyi Wang, Todd Goodwin, Novel association of ocular myasthenia gravis with Brown syndrome in an adult, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 2, February 2025, rjaf059, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf059

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Brown syndrome is an ocular misalignment disorder affecting the superior oblique tendon-trochlea complex. We report a case of a 45-year-old woman with protracted symptoms of presumed idiopathic Brown syndrome later diagnosed as ocular myasthenia gravis. Acquired Brown syndrome secondary to ocular myasthenia gravis has not previously been reported in the literature. Ocular myasthenia gravis should be considered a differential in any patient presenting with vertical strabismus presenting as Brown syndrome.

Introduction

Brown syndrome is an ocular misalignment disorder characterized by limitation in elevation of the affected eye in adduction [1]. The etiology of Brown syndrome is broad and can be classified into congenital, acquired, or idiopathic [2]. Congenital Brown syndrome is secondary to anomalies at birth to the trochlear apparatus, superior oblique (SO) muscle or SO tendon, whereas acquired forms of Brown syndrome can result from autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), scleroderma, or rheumatoid arthritis [2]. Scarring from previous surgical procedures or trauma to the SO tendon as well as inflammatory processes are also potential causes of Brown’s syndrome [3]. In this report, we present a novel case of bilateral, sequential Brown syndrome in an adult female who presented asynchronously with the left eye affected first, then subsequently developed bilateral symptoms, which was later diagnosed as ocular myasthenia gravis.

Case report

A 45-year-old female patient presented to the ophthalmology clinic with an 8-day history of binocular vertical diplopia and subjective restriction in elevation. Past medical history includes hypothyroidism and polycystic ovarian syndrome with no previous ocular history or surgeries.

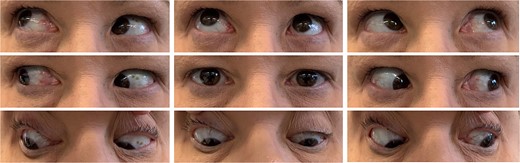

On examination, her best corrected visual acuity was 6/4.5 bilaterally with normal intraocular pressures and round, equal pupils reactive to light and accommodation. Extraocular motility testing revealed mild (−1) restriction in elevation in adduction of the left eye with pain on right gaze (Fig. 1). The cover test demonstrated left hypotropia measuring 4 prism diopters (PD). Her anterior and posterior segment examinations were unremarkable.

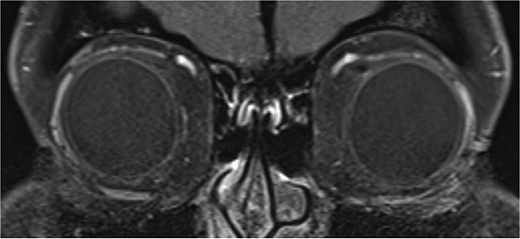

Initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits with contrast was normal (Fig. 2). However, the patient’s symptoms were suspicious for acquired Brown syndrome associated with an inflammatory etiology. As such, she was trialed on regular ibuprofen 400 mg three times daily.

T1 coronal image of orbits which shows normal symmetrical superior obliques.

Five days later, she re-presented with increased pain in the left trochlear region and worsening binocular vertical diplopia despite initial improvement with ibuprofen. On examination, she had moderate (−2) limitation in elevation in adduction in the left eye, with the remainder of the motility examination stable from previous. Given the progression in symptoms and clinical findings, a decision was made to commence oral prednisolone 25 mg daily. Following this, while the patient continued to experience diplopia and no change in motility deficit on examination, she reported subjective improvement in pain.

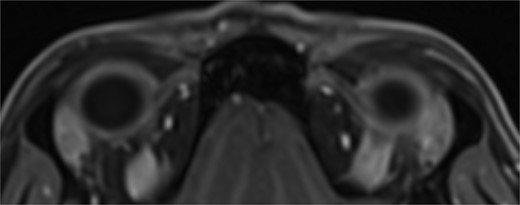

One month from initial presentation, the patient’s motility deficit progressed to bilateral moderate (−2) elevation deficit in adduction. A repeat MRI orbits yielded normal findings: there was no hypertrophy of the SO, no inflammation/hypertrophy of extraocular muscles, and no trochlear attachment (Fig. 3). Rheumatology input was sought regarding the possibility of acquired Brown syndrome; however, serology for mixed connective tissue disease, SLE, and rheumatoid arthritis was negative. The patient was treated for a total of 11 months on oral prednisolone at a maximum of 50 mg daily, which was slowly tapered and replaced with steroid-sparing, immune-modulating agents methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine.

T1 axial image of orbits which shows a normal trochlear-tendon complex.

One year post-presentation, the patient continued to suffer protracted symptoms of diplopia and motility deficit coupled with the new development of bilateral ptosis and limb weakness, which subsequently prompted myasthenia gravis testing. The acetylcholine receptor antibody assay was positive (4.14 nmol/L) confirming seropositive ocular myasthenia gravis. The patient tested negative (<0.01 U/ml) for muscle-specific tyrosine kinase antibodies. With the diagnosis of ocular myasthenia, the patient was commenced on pyridostigmine 180 mg. Within weeks, her diplopia had significantly improved with near full resolution of extraocular motility deficit.

Discussion

There is no precedence of a case of ocular myasthenia gravis masquerading initially as bilateral Brown syndrome in an adult. Myasthenia gravis is known to have great variability in its presentation and can mimic other pathologies [4]. Although there are no known risk factors for myasthenia gravis, the patient’s prior hypothyroid disease may have been an aggravating factor [4].

Bilateral idiopathic Brown syndrome typically presents in children aged between 2 and 8 years as opposed to adults [5]. The majority of acquired Brown syndrome in adults has been associated with autoimmune connective tissue disorders such as scleroderma or SLE with a proposed mechanism of action similar to stenosing tenosynovitis [6–8]. Generally, MR imaging of patients with acquired Brown’s demonstrates abnormal thickening of the SO tendon [9]. Likely the initial restrictive strabismus symptoms were related to acetylcholine receptor blockade of the SO congruent with the pathophysiology of myasthenia gravis, rather than the SO tendon itself being involved [10, 11]. This may explain why the patient’s MRI remained normal despite ongoing symptoms over the course of over 2 years.

Acquired Brown syndrome secondary to ocular myasthenia gravis has not previously been reported in the literature. Ocular myasthenia gravis should be a differential in any patient presenting with vertical strabismus presenting as Brown syndrome.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was required for this study and the authors have no financial disclosures.

Patient consent for publication

Written consent for publication and clinical images was obtained from the patient.