-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gonçalo Tardão, Filipe Moraes, Sandra R Barros, Ana Cardoso, Nuno Campos, Phototherapeutic keratectomy for calcific band keratopathy secondary to multiple myeloma, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 2, February 2025, rjaf046, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf046

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

To report a case of calcific band keratopathy (CBK) secondary to multiple myeloma (MM) successfully treated with phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK). An 80-year-old woman presented with progressive vision loss in her left eye with a best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 4/10 in the left eye (OS). Slit-lamp examination revealed a central band-like corneal opacification indicative of CBK. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT) showed a subepithelial hyper reflective layer. Further evaluation confirmed an indolent IgAk MM, with no indication for systemic therapy. PTK was performed using the Technolas® TENEO™ 317 M2 excimer laser, resulting in corneal surface regularization and BCVA improvement. At 1-year follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic, had a clear cornea, normal topography, and a BCVA of 10/10. CBK can be associated with systemic conditions. PTK is an effective and safe procedure for managing CBK, and can provide complete visual rehabilitation.

Introduction

Calcific band keratopathy (CBK) is a corneal degeneration characterized by the accumulation of fine, dust-like deposits in the superficial layers of the cornea. This condition can arise from both ocular and systemic conditions, necessitating through etiological investigation when no apparent cause is identified [1–3].

Hypercalcemia associated with multiple myeloma (MM) can manifest as CBK and it is essential to rule this out through clinical evaluation and laboratory analysis. The management of CBK should target the underlying disease. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) treatment is considered the first-line therapy for mild cases. In more instances, debridement, with or without superficial smoothening via Phototherapeutic Keratectomy (PTK), is typically preferred [3–5].

This case report highlights the effectiveness of managing mild CBK secondary to MM using PTK as primary treatment modality.

Case report

An 80-year-old woman presented to our clinic with progressive vision loss and discomfort in her left eye, persisting for 6 months. She reported no additional symptoms and had no history of trauma or recent medication use. Her past medical history was notable for depression, for which she was taking escitalopram 20 mg daily. Ophthalmological history included uncomplicated cataract surgery in both eyes.

Upon examination, the uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) at 6 m measured 5/10 in the right eye (OD) and 2/10 in the left eye (OS). Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 10/10 with +1.25–2.00 × 60° in OD, and 4/10 with +0.25–1.25 × 100° in OS.

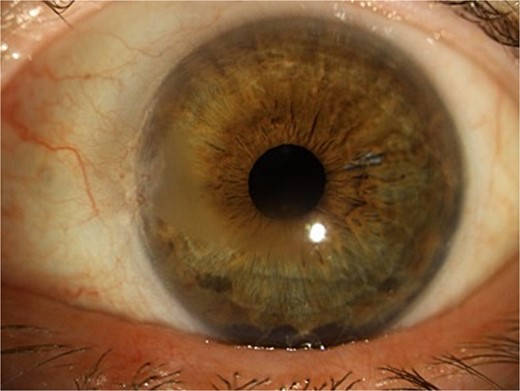

Slit-lamp examination revealed a 6 × 3 mm sub-epithelial gray–brown opacity in a band-like configuration at 9 o’clock meridian in OS, sparing the limbus (Fig. 1).

Slit-lamp examination showing gray horizontal opacity with paracentral and inferior involvement.

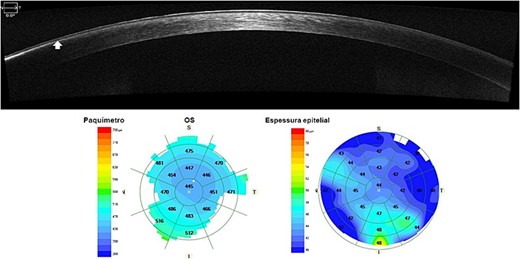

Anterior segment optic coherence tomography (AS-OCT) using the Cirrus HD-OCT 5000 revealed a thin hyper reflective band involving the Bowman’s layer, accompanied by a shadowing effect (Fig. 2). The epithelial map appeared normal.

AS-OCT with epithelial map showing a thin nasal sub-epithelial hyper reflective band with posterior shadowing. A denser hyper reflective zone can be noticed at the periphery.

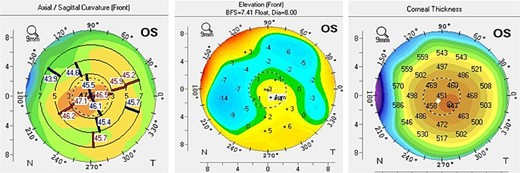

Scheimpflug imaging (Pentacam HR, Oculus Wetzlar, Germany) revealed irregular astigmatism, as shown by sagittal curvature maps and anterior elevation maps, with a central corneal thickness of 461 μm (Fig. 3).

Scheimpflug imaging showing irregular astigmatism and superficial irregularity.

Further analytical investigation indicated pancytopenia. Serum calcium levels registered at 8.8 mg/dL, with a prior history of uninvestigated hypercalcemia (>10.5 mg/dL). Serum electrophoresis revealed a monoclonal spike in the Beta-Gama region, with elevated IgA (879 mg/dL) and kappa light chain (435 mg/dL). A bone marrow biopsy indicated plasmacytic infiltration (30%) and medullary hypocellularity (<50%), leading to a diagnosis of indolent IgA k MM.

Due to absence of available EDTA treatment, PTK was considered, and the patient informed of expected results and possible complications.

PTK was performed under topical anesthesia using the Technolas® TENEO™ 317 M2 excimer laser for superficial ablation. The optical treatment zone was set to 7.0 mm with an ablation depth of 30 μm following 20% alcohol de-epithelization. Balanced salt solution (BSS) was applied as a masking agent to minimize post-procedure irregularity and hyperopia.

There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications. Postoperative care included placement of a bandage hydrogel silicone soft contact lens (Air optix night & day aqua, Alcon), along with topical dexamethasone 0.1% four times a day (QID) and preservative-free artificial tears QID.

At 1-week post-operation, slit-lamp examination demonstrated clarity of the visual axis with no signs of deposits and confirmed epithelial closure. The bandage contact lens was removed after 2 weeks.

At the 1-year follow-up, patient was solely using preservative-free artificial tears. Her UCVA was recorded at 4/10 and her BCVA improved to 10/10 with a prescription of +1.50–1.50 × 130° in OS.

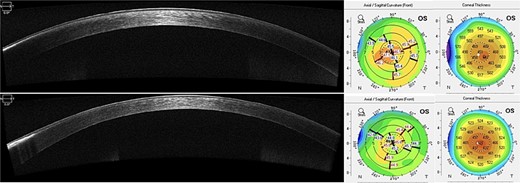

AS-OCT revealed an improvement in the hyper reflective band in the treated area. Scheimpflug imaging displayed superficial regularization and a predictable decrease in central corneal thickness of 20 μm (Fig. 4).

AS-OCT at 1-year postoperatively shows improvement of the paracentral hyper reflective band. A worsening in the peripheral untreated are can also be noticed. Scheimpflug imaging demonstrates thinning of central corneal thickness and reduction of mean anterior keratometry (45.3D) with superficial regularization.

Discussion

CBK may arise in the context of both local and systemic diseases [1–3]. While most patients with CBK present with an already recognized underlying condition, it may also be the initial manifestation of hypercalcemia [2].

Although the cornerstone of CBK management is the resolution of the underlying conditions, this typically does not reverse corneal findings. However, some reported cases have shown spontaneous regression and visual improvement following chemotherapy, as described by Wilson et al. [2]. Johnston et al. also reported a patient who achieved nearly complete resolution 6 months after calcium regularization [3].

EDTA 2%–3% chelation therapy is considered the standard treatment for CBK, yielding satisfactory outcomes and resulting in a clear visual axis in ⁓97.8% of cases [4]. PTK or manual keratectomy can be employed if superficial irregularities persist after calcium removal or in severe cases. PTK has the advantage of enabling precise tissue removal while minimizing trauma to adjacent structures and providing smooth ablation zones [5].

For rough calcific bands, the removal of plaques with forceps must be performed before EDTA chelation, manual debridement, or PTK, and a masking agent should always be used during PTK [5].

In this case, as EDTA was unavailable, the patient underwent isolated PTK for the removal of CBK. Although isolated PTK for calcium removal is generally not recommended as the primary approach due to concerns about uneven ablation potentially inducing astigmatism and hyperopic refractive changes, PTK has been shown to be both effective and safe without EDTA chelation, particularly in cases resistant to chelation therapy [1, 5]. Astigmatism can be mitigated by employing a masking agent to fill in irregularities and achieve regularization of the corneal surface. In this case, BSS was used with successful outcomes. Refractive surprises can be minimized through accurate measurement of band depth using AS-OCT and continuous intraoperative monitoring of the corneal surface to assess the presence of calcium deposits, thereby preventing unnecessary ablation. Transepithelial PTK may serve as an alternative approach when the epithelium is smooth but the underlying stroma is irregular, as the epithelium can act as a natural masking agent.

In this report, we highlight that PTK can be an effective and safe alternative for the treatment of smooth CBK when EDTA chelation is not feasible.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

None declared.

Patient consent

Written consent to publish this case has not been obtained. This report does not contain any personal identifying information.

Financial disclosures

The authors have no financial disclosures.