-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Ching-Shya Yong, Tien-Fa Hsiao, Ying-Lun Wei, Tsung-I Hung, Yenn-Hwei Chou, Cheuk-Kay Sun, Complete duodenal disruption from blunt abdominal trauma successfully managed with multistage surgical and endoscopic interventions: a case report, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 11, November 2025, rjaf955, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf955

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Complete duodenal disruption from blunt abdominal trauma is rare but life-threatening, especially when involving the second and third portions near the ampulla of Vater, which are essential for bile and pancreatic drainage. Such injuries predispose to high-output fistulas, nutritional depletion, and fatal complications. We report a 51-year-old male with multiple abdominal injuries after a high-speed collision, including superior mesenteric vein rupture and complete duodenal disruption. Initial management involved vascular repair and temporary duodenal closure, followed by staged reconstruction with gastrojejunostomy, pyloroplasty, and feeding jejunostomy. Despite these measures, duodenal stump leakage with a high-output biliary fistula developed. Given the hostile operative field, a third-stage multidisciplinary approach was undertaken: endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy with endoscopic nasobiliary drainage placement plus surgical drainage. The patient demonstrated clinical improvement, underscoring the value of multidisciplinary collaboration and therapeutic endoscopy in complex duodenal trauma.

Introduction

Blunt abdominal trauma is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in high-impact accidents, and duodenal injuries, although uncommon, pose significant management challenges due to their retroperitoneal location and proximity to major vascular and biliary structures [1]. This anatomical region houses the ampulla of Vater, a critical site where bile and pancreatic secretions enter the gastrointestinal tract. Associated injuries to adjacent organs, such as the pancreas, bile duct, or major vessels, further complicate management. Initial surgical repair is often required but is frequently complicated by massive bile leakage and high-output fistulas, which are notoriously difficult to control and may lead to severe nutritional depletion, electrolyte imbalance, and increased mortality risk [2, 3]. In severe cases, surgical interventions such as biliary diversion or pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) may be considered; however, these carry significant morbidity and are rarely feasible in unstable trauma patients [3]. Postoperative complications, such as duodenal stump leakage, remain particularly challenging and often demand innovative, multidisciplinary solutions [4, 5]. In this case, a multistage surgical approach was employed, followed by the novel use of endoscopic ultrasound-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS) with endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD). This case underscores the evolving role of therapeutic endoscopy in trauma care, especially when adhesions, fragile tissues, or complex anatomy limit conventional surgery.

Case presentation

A 51-year-old male with a history of hypertension sustained multiple injuries in a high-speed motor vehicle accident. The patient was entrapped for approximately 30 minutes and presented to the emergency department with blunt abdominal trauma and an open fracture of the left tibia. On arrival, the patient was hypothermic (26.1°C), tachycardic (37 bpm), and initially normotensive (133/122 mmHg), with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of E3V4M6. Primary survey revealed ecchymosis over the upper abdomen and left leg deformity. Focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) demonstrated massive hemoperitoneum (Fig. 1). Despite initial resuscitation, the patient’s condition deteriorated rapidly within 10 minutes, with a drop in GCS to E1V1M4 and blood pressure to 70/55 mmHg, consistent with hypovolemic shock. Trauma red activation was initiated. Bedside sonography revealed rapidly increasing intra-abdominal free fluid. The patient experienced two episodes of pulseless electrical activity (PEA), both successfully resuscitated, and was transferred to the operating room within 15 minutes for emergency exploratory laparotomy.

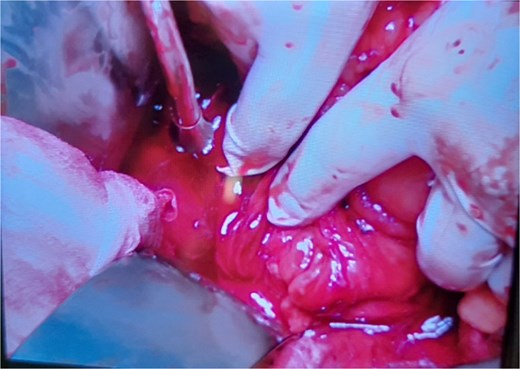

Intraoperative findings included rupture of the superior mesenteric vein at two sites, resulting in massive hemoperitoneum; >95% circumferential disruption of the second and third portions of the duodenum with only minimal posterior serosal continuity; laceration of the pancreatic uncinate process; jejunal perforation; ischemic perforation of the transverse colon due to mesocolon devascularization; and a right retroperitoneal hematoma (Fig. 2). The pancreas was markedly swollen, precluding reliable assessment of parenchymal or ductal injury at that time. Given the hemodynamic instability, damage control surgery was performed, which included repair of the superior mesenteric vein, segmental resection of the transverse colon with proximal colostomy, small bowel repair, and temporary closure of both ends of the disrupted duodenum. A nasogastric tube was inserted for bile drainage. The operation lasted ~3 hours, with an estimated blood loss of 5000 ml.

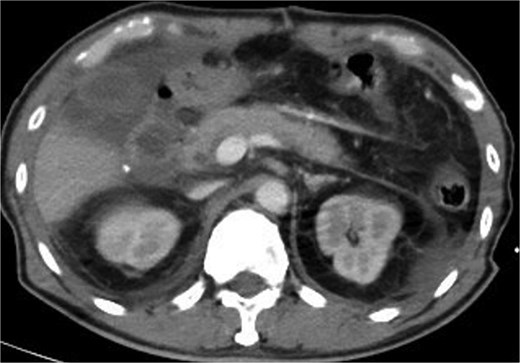

After stabilization in the surgical intensive care unit, a contrast-enhanced whole-body computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 3) on postoperative day 2 revealed no active bleeding or pancreatic parenchymal/ductal injury. On postoperative day 5, the patient underwent staged reconstruction. Intraoperative findings demonstrated extensive bile leakage from the anterior wall of the second portion of the duodenum, consistent with advanced erosion and friable tissue, which precluded the feasibility of a Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy. Reconstruction consisted of gastrojejunostomy and pyloroplasty, colonic anastomosis, and feeding jejunostomy. Postoperative care included total parenteral nutrition with gradual advancement to jejunostomy feeding. The patient subsequently developed a delayed liver laceration with intra-abdominal hematoma, traumatic pancreatitis, gastrojejunostomy leakage, and colonic anastomotic leak, all of which were managed conservatively. Nevertheless, the course was complicated by duodenal stump leakage with a high-output biliary fistula refractory to standard management, with drainage volumes reaching ~1000 ml/day.

CT scan showed no active bleeding or pancreatic parenchymal/ductal injury.

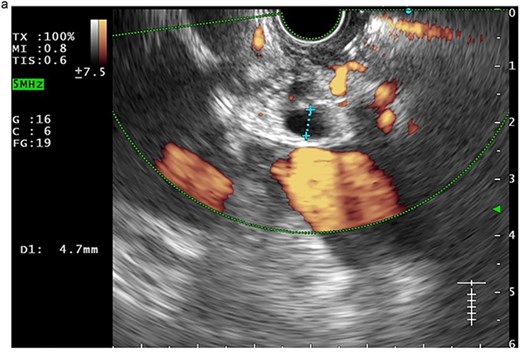

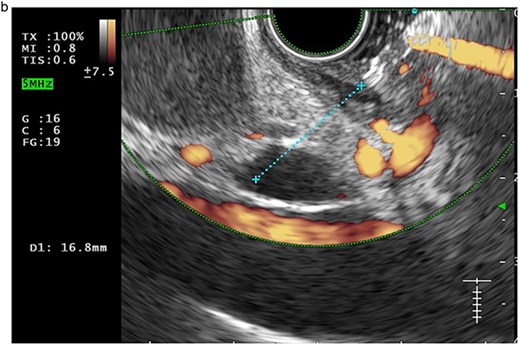

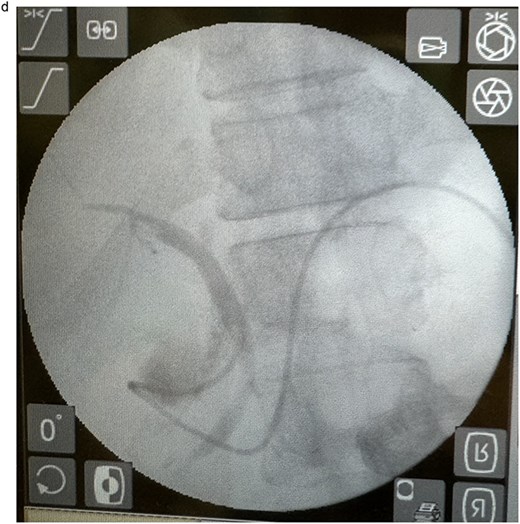

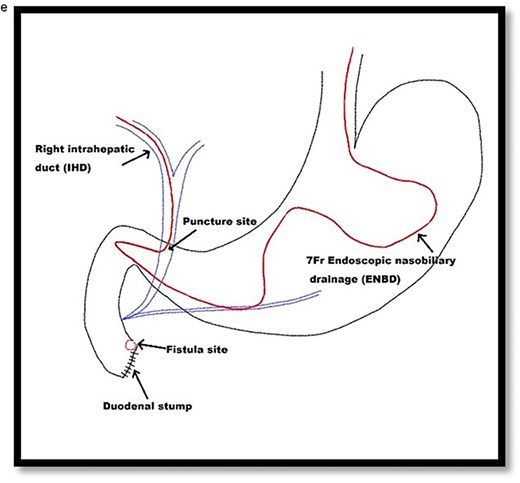

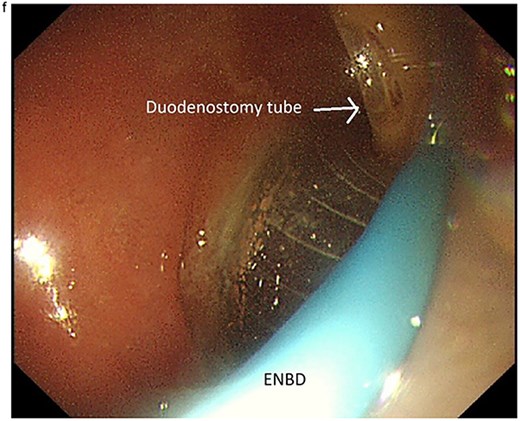

In view of the ongoing leakage and the hostile operative field, a third intervention was undertaken on postoperative day 24 following the second surgery. After multidisciplinary discussion, a combined surgical–endoscopic approach was undertaken in collaboration with internal medicine specialists. Intraoperative findings revealed dense adhesions from prior surgeries and a 0.5-cm perforation at the proximal duodenal stump, located near the ampulla of Vater. Initial endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was unsuccessful due to limited ampullary access; thus, EUS-CDS with ENBD placement was performed as an alternative strategy. From the duodenal bulb, the common bile duct (CBD) measured 4.7 mm on EUS, and Doppler confirmed no intervening vessels (Figs 4a and 4b). A 19-gauge EZ Shot 3 needle (Olympus) was used to puncture the extrahepatic bile duct, and bile aspiration followed by contrast injection confirmed correct positioning (Fig. 4c). A VisiGlide 2 angled guidewire (0.025 inch) was advanced into the right intrahepatic duct, and the tract was dilated using an ES dilator. A 7-Fr ENBD catheter was subsequently deployed across the choledochoduodenostomy under fluoroscopic guidance, achieving effective biliary drainage (Figs 4d and 4e). In addition, a 16-Fr Foley catheter was inserted into the duodenal perforation as a duodenostomy tube (Fig. 4f) for external drainage, and six closed wound vacuum drains were placed for peritoneal irrigation and drainage.

Schematic illustration of EUS-CDS with placement of a 7-Fr ENBD catheter into the right intrahepatic duct.

Endoscopic image demonstrating the 7-Fr ENBD catheter, with concurrent visualization of the duodenostomy tube at the proximal duodenal stump.

This combined approach achieved effective biliary diversion and clinical improvement. Total biliary drainage, including duodenostomy and ENBD output, stabilized at ~500 ml/day. During this period, oral intake was gradually resumed, supplemented by jejunostomy feeding. Once biliary output plateaued and clinical stability was achieved, the ENBD catheter was removed 2 months later. All external drainage tubes, including the duodenostomy, were subsequently removed. The patient advanced to full oral intake, jejunostomy feeding was discontinued, and the tube was removed without complication. Recovery was uneventful, with restoration of bowel function. Postoperative CT (Fig. 5) confirmed an intact gastrointestinal tract without obstruction.

Post-intra-abdominal/intestinal with non-obstructive adhesion, no detectable apparent oral contrast leak, and no pancreatobiliary ductal dilatation.

Discussion

Duodenal injuries account for fewer than 5% of abdominal trauma and are frequently associated with other organ damage, making management challenging [1]. Primary repair or pyloric exclusion is feasible in many cases, but postoperative leakage and fistula formation remain serious complications [2]. In this patient, staged operations stabilized vascular and bowel injuries, yet persistent duodenal stump leakage required an alternative strategy. Historically, complex reconstructions such as Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy, duodenal diverticulization, or pancreaticoduodenectomy were considered [3], but hemodynamic instability, adhesions, and tissue edema rendered reoperation prohibitively morbid. Endoscopic approaches, particularly EUS-CDS with ENBD, have been established for malignant obstruction and benign strictures [4], and are increasingly reported for gastrointestinal leaks when re-entry is high risk [5]. Here, EUS-CDS with ENBD provided effective biliary diversion, avoided the morbidity of complex reconstruction, and enabled recovery. This experience underscores the importance of multidisciplinary collaboration and highlights the potential role of therapeutic endoscopy in the evolving management of complex trauma.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

None declared.

References

- ultrasonography

- endoscopy

- pathologic fistula

- gastrojejunostomy

- abdominal injuries

- amputation stumps

- bile fluid

- biliary fistula

- malnutrition

- creation of jejunostomy

- reconstructive surgical procedures

- rupture

- surgical procedures, operative

- vater's ampulla

- duodenum

- duodenal injuries

- pyloroplasty

- choledochoduodenostomy

- pancreatic duct drainage

- blunt abdominal injuries

- superior mesenteric vein

- vascular repairs

- endoscopic ultrasound