-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Christina Regelsberger-Alvarez, Scarlett B Hao, Sarah K Struble, Kieran J Ved, Management of spontaneous atraumatic splenic rupture in the setting of anticoagulation: case report and literature review, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 11, November 2025, rjaf924, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf924

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

A 69-year-old male with a history of atrial fibrillation on apixaban with no recent history of trauma presented with acute onset abdominal pain and hypotension with no identified precipitating event. Intraabdominal free fluid was noted on bedside ultrasound, and computed tomography angiography of the abdomen showed splenic rupture. Anticoagulation was reversed with prothrombin complex, and he was taken to the operating room for emergent splenectomy. Spontaneous splenic rupture is uncommon, but as with traumatic splenic injuries, it may be managed operatively or non-operatively. In patients on therapeutic anticoagulation, reversal agents should be considered. Spontaneous splenic rupture may lead to life-threatening hemorrhage, particularly for patients on therapeutic anticoagulation. This case highlights the importance of timely diagnosis and operative intervention as well as the role of anticoagulation reversal for these patients.

Introduction

Spontaneous atraumatic splenic rupture can be life-threatening if not diagnosed and treated promptly. The threat of uncontrolled hemorrhage is greater in the setting of pre-rupture anticoagulation. No guidelines exist on anticoagulation management in this clinical context. We present a case report of a patient on therapeutic anticoagulation who developed spontaneous splenic rupture, which was managed with good outcome.

Case report

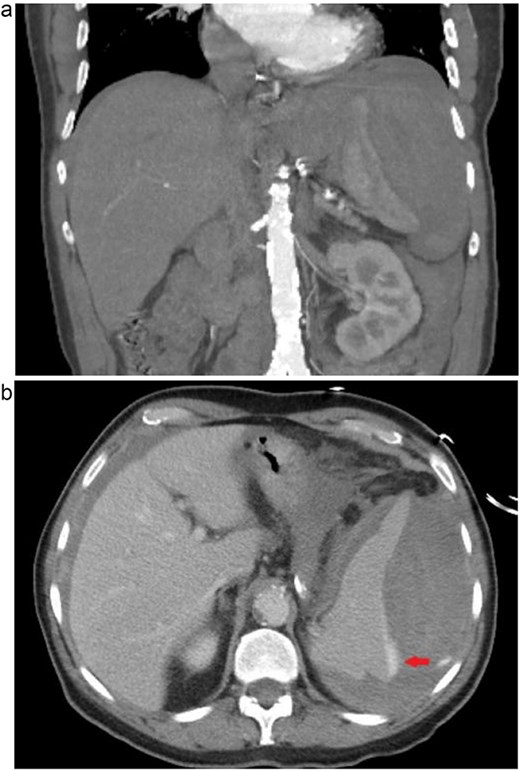

A 69-year-old male patient with a history of 50 pack years of smoking, atrial fibrillation on apixaban, coronary artery disease, and hypertension presented to the emergency department at a tertiary care hospital by ambulance with acute onset abdominal pain and a syncopal event at home six hours prior. The patient was hypotensive with blood pressure of 67/53 mmHg en route, which improved to 142/70 mmHg after 500 ml of normal saline and 5 mcg of epinephrine. An additional 1 l of saline and 1 unit of packed red blood cells were given with continued hemodynamic response. The patient reported no recent history of trauma or change in health. Bedside ultrasound revealed large volume free fluid in the abdomen. Computed tomography angiography of the abdomen demonstrated acute splenic rupture with active extravasation (Fig. 1). Tranexamic acid was administered. Prothrombin concentrate was given to reverse the apixaban. The patient again became hypotensive to 84/55 mmHg and was taken emergently for exploratory laparotomy and splenectomy. Intraoperatively, it was found that most of the splenic attachments had already avulsed. Remaining attachments to the diaphragm were taken down, the short gastric ligated, and the hilum transected. Intraoperative blood loss was 4 l, with 1.7 l returned through auto-transfusion. Postoperatively, he was admitted to the intensive care unit for monitoring overnight. The patient did not require further transfusion. He was able to transition to the surgical floor, advance diet, and discharge to home on postoperative day 5. Prior to discharge, the patient received meningococcal, pneumococcal, and Haemophilus vaccinations. No complications were identified at the 2-week postoperative follow-up outpatient visit, and the patient was able to restart his apixaban without issue. Pathologic review of the specimen did not identify abnormality to explain the rupture.

(a) Coronal computed tomographic angiogram image of ruptured spleen with large amount of surrounding perisplenic hematoma. (b) Axial computed tomographic angiogram image of ruptured spleen, arrow indicating extravasation of contrast dye.

Discussion

Case reports of the phenomenon of atraumatic splenic rupture have continued to appear in the medical literature from its earliest documentation in 1861 to the present day, but its true incidence remains elusive [1]. Proposed etiologies based on the body of evidence include infection, neoplasm, inflammation, and hematologic causes. Atraumatic splenic rupture appears to occur more commonly in men, affects nearly all ages, and presents with hypotensive shock in about a third of cases [1]. A small percentage of patients die before surgical intervention, with the diagnosis discovered at the time of autopsy [1].

Management of atraumatic splenic rupture largely mirrors management of traumatic splenic injury. Conservative non-operative observation can be pursued if the patient is not in extremis and the etiology can be identified and treated. Several case series of patients with atraumatic splenic rupture due to infectious mononucleosis have described successful conservative management [2]. The advantages of spleen preservation include retaining the spleen's immune function and avoiding the morbidity of splenectomy [1]. In addition, angiographic embolization of the splenic bleed has been described for atraumatic splenic rupture, including cases of a patient with concurrent Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection, other infections, and leukemia [3–5].

In the setting of therapeutic anticoagulation, the evidence largely describes operative management for atraumatic splenic rupture, with or without preoperative embolization [6]. The reported cases vary in their description of the use of a reversal agent, most commonly prothrombin complex concentrate [7–9]. Current trauma guidelines do not specifically mandate usage of reversal agents in the management of blunt traumatic splenic injury in the setting of preinjury anticoagulation, but studies have found higher failure rates of conservative management and higher mortality for these patients [10]. Therefore, in cases of truly idiopathic spontaneous atraumatic splenic rupture, we strongly recommend providers not only follow guidelines for traumatic splenic injury, but also consider anticoagulation reversal and operative management in unstable patients.

In conclusion, idiopathic spontaneous atraumatic splenic rupture leading to hemorrhage can be life-threatening, more so in the setting of therapeutic anticoagulation. We present a clinical case of atraumatic splenic rupture in a patient on anticoagulation with no other identifiable precipitating etiology. While many patients with atraumatic splenic rupture can be managed non-operatively, for patients on therapeutic anticoagulation, splenectomy is recommended, and reversal of anticoagulation should be considered.

Conflict of interest statement

This report has no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this report.