-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Roberto Cunha, Francisco Basilio, Ricardo Gouveia, Vitor Martins, Alexandra Canedo, Breaking the Nutcracker: a case-based review of diagnosis and surgical treatment, Journal of Surgical Case Reports, Volume 2025, Issue 11, November 2025, rjaf920, https://doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rjaf920

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Nutcracker syndrome is a rare condition caused by compression of the left renal vein between the abdominal aorta and the superior mesenteric artery. This results in increased venous pressure, leading to haematuria, flank pain, and pelvic discomfort, particularly in individuals with low body mass index. Diagnosis is often challenging due to nonspecific symptoms and overlap with other pelvic disorders. We report a case of a 49-year-old woman with persistent left flank pain, dysmenorrhea, and recurrent vaginal bleeding. Imaging confirmed compression of the left renal vein. A conservative approach with nutritional support was initially attempted, but due to ongoing symptoms, the patient underwent surgical transposition of the vein with patch angioplasty using bovine pericardium. This case underscores the need to consider Nutcracker syndrome in patients with unexplained haematuria and flank pain, especially in underweight women. We also review current diagnostic tools and treatment options for this uncommon vascular condition.

Introduction

Compression of the left renal vein (LRV) between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) is known as the Nutcracker phenomenon when asymptomatic, and as Nutcracker syndrome (NCS) when associated with symptoms due to LRV hypertension [1]. A rarer form, posterior NCS, involves a retroaortic LRV compressed between the aorta and vertebral column [2].

The prevalence of NCS is unknown, partly due to underdiagnosis. It can occur at any age, with peaks in young adults and middle age [3], and may affect both sexes [4].

Common symptoms include haematuria, proteinuria, and left-sided flank or pelvic pain. These are nonspecific and may overlap with pelvic congestion syndrome, complicating diagnosis [2]. Differential diagnoses include pancreatic tumours, lymphadenopathy, retroperitoneal masses, low retroperitoneal fat, and pregnancy [5].

We report a case of a woman with NCS who underwent LRV transposition with patch reconstruction, following persistent symptoms despite conservative treatment.

Case report

A 49-year-old woman with chronic gastritis and dyslipidaemia was under Urology and Gynaecology follow-up for left flank pain, dysmenorrhea, and frequent vaginal bleeding. Investigations including cystoscopy, transvaginal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) angiography, and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed three intramural uterine leiomyomas and a Nutcracker phenomenon.

She was referred to vascular surgery. The flank pain had started a year earlier, coinciding with an unintentional weight loss of 12 kg. Pain intensity was 8/10, with no clear triggers. Her body mass index (BMI) was 15.8 kg/m2 (45 kg, 1.68 m). Despite being followed in a chronic pain clinic, symptoms persisted and she lost her job. Nutritional support was initiated to promote weight gain.

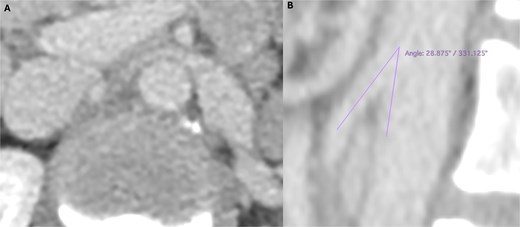

Lab tests showed microscopic haematuria (>0.45 × 106/l). Doppler ultrasound revealed LRV compression, with a diameter reduction from 12.5 to 1.5 mm, and a peak systolic velocity increase from 34 to 160 cm/s (velocity ratio > 4). CT angiography (Fig. 1) confirmed an aortomesenteric angle of 28° and ectasia of the left ovarian vein (9 mm).

Preoperative computed tomography angiography demonstrating compression of the left renal vein in axial section (A) and sagittal section (B), revealing an aortomesenteric angle of 28°.

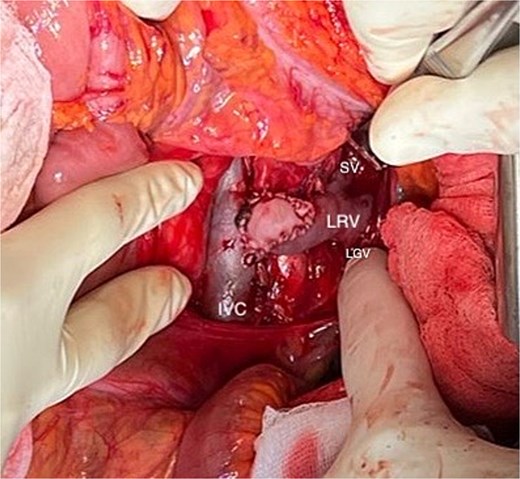

After 6 months, her weight increased to 52 kg, but pain persisted. Surgical LRV transposition with bovine pericardial patch angioplasty was performed (Fig. 2). The postoperative course was uneventful, with complete pain resolution and patent LRV confirmed by Doppler ultrasound on Day 6.

Final outcome of the left renal vein (LRV) transposition with patch angioplasty using bovine pericardium. (LGV: left gonadal vein; SV: suprarenal vein).

She was discharged on rivaroxaban® 20 mg and aspirin® 100 mg. Doppler follow-ups were conducted biweekly for a month, then monthly for 3 months, and then every 6 months, consistently showing LRV patency.

Due to persistent dysmenorrhea, anticoagulation was discontinued, with antiplatelet therapy maintained. She was referred back to Gynaecology. No further emergency department visits were recorded during the 6-month follow-up period.

Discussion

NCS can significantly impair quality of life and may lead to complications such as chronic kidney disease or LRV thrombosis, although these are rare. Symptoms like left flank pain, haematuria, and orthostatic proteinuria are primarily due to venous hypertension, which may disrupt small peripelvic veins. Proteinuria may also relate to hemodynamic shifts during standing, involving angiotensin II and norepinephrine release [4]. Low BMI and increased physical activity are recognized exacerbating factors [1].

Due to symptom overlap with conditions like pelvic congestion syndrome, diagnosis is challenging. Doppler ultrasound is a non-invasive first-line tool with sensitivity of 69%–90% and specificity of 89%–100% [4]. A PSV ratio > 4.2–5.0 between the compressed and hilar LRV segments is suggestive of NCS [6], though results can be influenced by hydration, body position, and operator experience.

On CT angiography, the ‘beak sign’ and a diameter ratio ≥ 4.9 between the hilar and aortomesenteric segments are highly specific [6]. An aortomesenteric angle <35° is also supportive. MRI avoids radiation and can reveal LRV compression and gonadal vein varices, though lacks dynamic flow assessment [4]. The gold standard remains venography showing a renocaval gradient ≥3 mmHg, with intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) as a useful adjunct [7].

Treatment depends on symptom severity. Conservative management, especially in younger patients, may include weight gain [5], angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (e.g. alacepril) for proteinuria, and low-dose aspirin [4]. In adults, persistent symptoms or gross haematuria after 6 months may require surgery [3].

Surgical options include LRV transposition, gonadocaval transposition, LRV-to-IVC bypass, nephropexy, autotransplantation, and nephrectomy as a last resort. Patch angioplasty or venous cuffs may reduce anastomotic tension. Technical considerations, like using two Prolene® sutures to avoid purse-string effect and declamping under Valsalva, help minimize complications such as deep vein thrombosis, haematoma, and vascular thrombosis [1]. Laparoscopic approaches may be suitable in experienced centres [4]. SMA transposition has been proposed but is discouraged due to risk of mesenteric ischaemia [4].

In endovascular therapy, stents like SMART Control™ and Wallstent™ have been used off-label, but carry risks including migration, erosion, and thrombosis [7]. No stent is currently designed specifically for NCS. Novel options like 3D-printed PEEK extravascular stents show promise but require further study [6]. Expert consensus advises caution with percutaneous approaches due to their complication rates [2].

Postoperative management varies. Some suggest 3 months of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy post-stenting [7], while others prefer dual antiplatelet therapy for 1 month, then aspirin alone [4]. Suggested follow-up includes Doppler at 6 weeks, then annually, although standardized protocols are lacking [2].

To conclude, by sharing this case, we aim to contribute to the growing body of literature on Nutcracker syndrome, providing valuable insights into treatment options, particularly regarding stenting and conservative management. Furthermore, this report underscores the need for further studies to establish standardized treatment protocols and long-term follow-up strategies, ultimately enhancing patient care and clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Luís Fernandes, Dr. Marta Machado, Dr. Patrícia Carvalho, and Dr. Beatriz Guimarães for their valuable support and collaboration throughout the development of this study.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical considerations

Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Consent to participate and for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

References

Heilijgers F, Gloviczki P, O'Sullivan G,et al. Nutcracker syndrome (a Delphi consensus). J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord 2025;13:101970.

.Author notes

This case report was conducted at Unidade Local de Saúde de Gaia e Espinho. The author has since moved to Hospital do Divino Espírito Santo.